Art fairs are very sad affairs, as a whole. The reduction of an entire artist’s practice to a few square feet of temporary drywall, the three-second interactions between gallery and client that render works of art little more than mathematical utterances, the absolute lack of critical (not just negative) observation that is delivered after the fact to a mass audience: what has this turned into? If art fairs are speeding towards commercialized oblivion, perhaps it screeches slightly into reverse at The Independent Art Fair, hosted during Armory Week every March in New York City.

This edition saw the fair return to its original location at the old Dia building on West 22nd Street in Chelsea. With each successive iteration, the fair draws bigger and more influential names into the social and institutional folds. Seen at the VIP preview were Massimiliano Gioni (of The New Museum), Don and Mera Rubell (collectors whose pet artist, Oscar Murillo, was recently named a participant in this year’s Venice Biennale) hobbled down the narrow staircases, among others. Many works were sold within the first thirty minutes of the fair’s opening. A loud, jubilant text piece by John Giorno was not only unavailable by 1pm, but multiple versions (according to staff at Elizabeth Dee Gallery) had already been sold or placed on reserve. But all of this means nothing when speaking for the quality of work presented, overall. Luckily, that was readily and widely available.

Standouts included a suite of found, flea-market paintings by Berlin-based Dirk Bell, which he had altered with sketches made with both white highlights and traditional paint, resulting in a series of subversive, often secret imagery.

Installation view

Dimensions variable

Courtesy of the artist and BQ, Berlin

Zürich-based Raebervonstenglin’s unified presentation of Thomas Wachholz and Raphael Hefti was a well-balanced play between minimal, crimson canvases and floor-to-ceiling-sized metal pipes taking cues from rolls of technicolored cellophane.

Installation view

Dimensions variable

Courtesy of the artists and Raebervonstenglin, Zürich

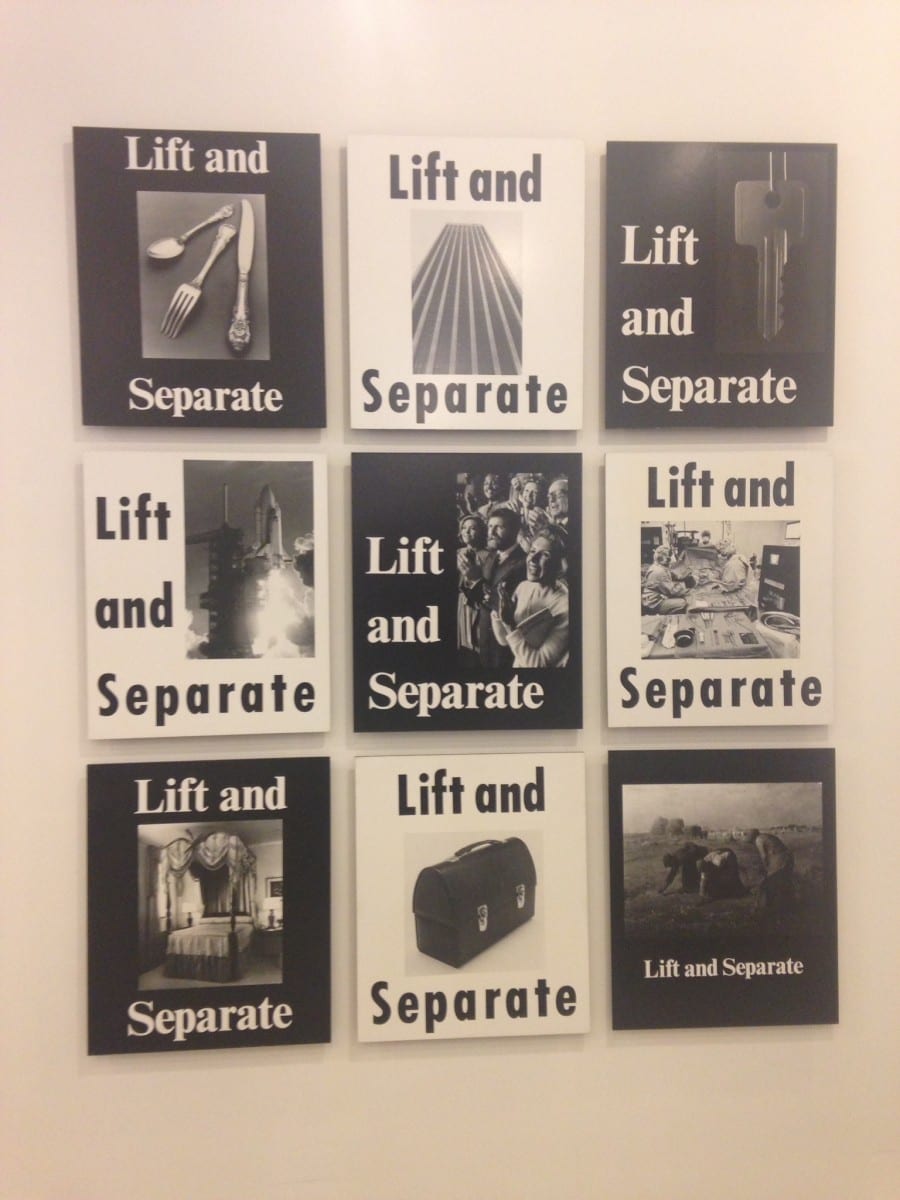

Another gallery hailing from Berlin, Croy Nielsen, set up a curious suite of black and white photographs (dating from the late 1970’s) mounted on board: each photograph depicted a stock image of an audience applauding, or a space shuttle in takeoff, or an albino gorilla being observed, or even a reproduction of Millet’s bourgeois masterpiece The Glenaers all accompanied by the same phrase, Lift and Separate. The arist, Mitchell Syrop, displays a keenly critical eye on the subliminal, often troubling messages buried within public advertising – not unlike those investigations carried out by Ed Ruscha, Richard Prince, or Barbara Kruger.

Lift and Separate, Black and white photographs, mounted on board

Installation view, 1984.

Courtesy of the artist and Croy Nielsen, Berlin

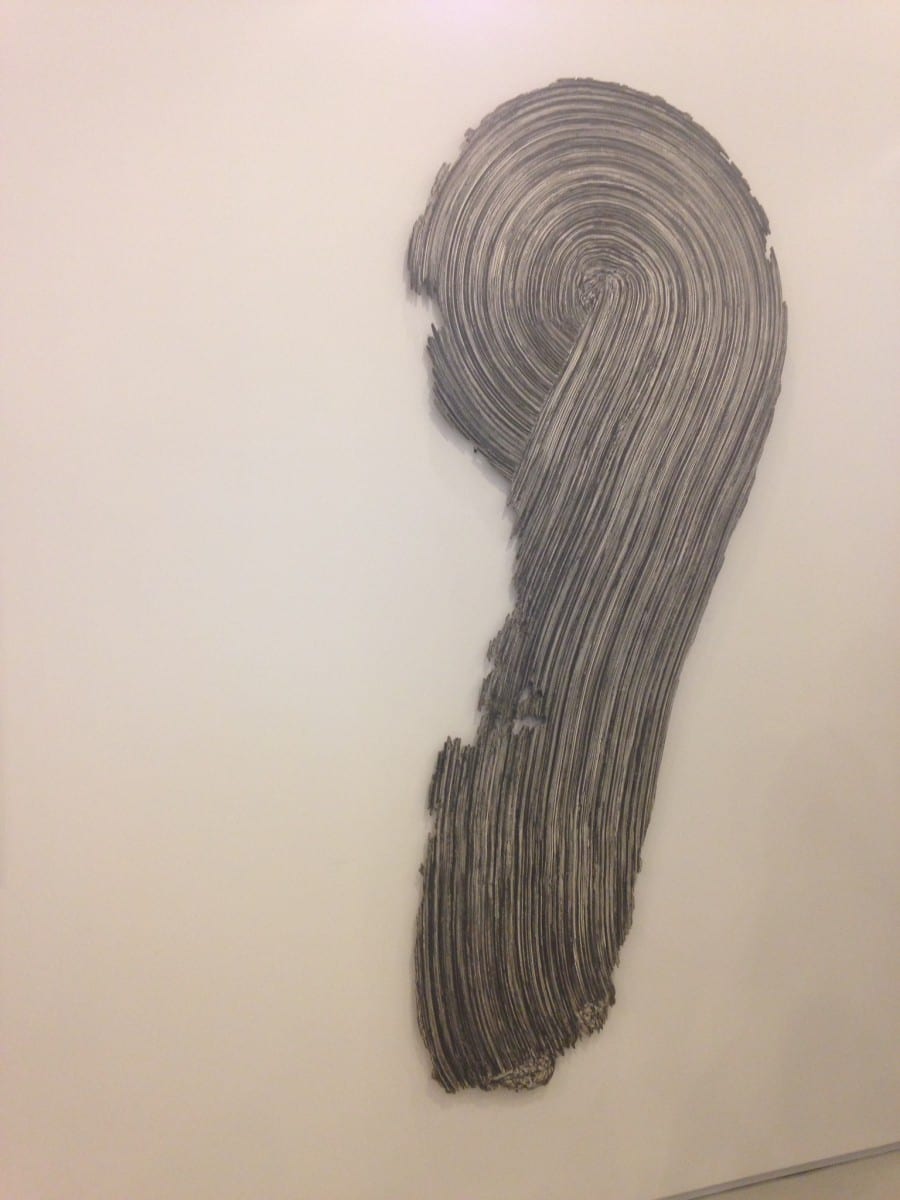

St., Gesso and graphite on masonite, 94″ x 42″, 1972.

Courtesy of the artist and Broadway 1602, New York

Another resurrection of “lost art” that was most welcome was delivered courtesy of Broadway 1602, with their roster consisting of (primarily women) artists working since the late 1960’s. Their installation of wall sculptures from Rosemarie Castoro was, undoubtedly, one of the fair’s most elegant entries. Castoro was married to Carl Andre long before he met Ana Mendieta, and her close friends and contemporaries included LeWitt, Martin, Wiener, and Smithson (the gallery’s mini-catalogue includes a “selfie”, executed by Castoro via self-timed Polaroid, of all of these figures seated in a small studio space). The gallery could have gone overboard in crying “foul” that Castoro never received the sort of attention that her male counterparts, or even women such as Agnes Martin, have enjoyed for the last four decades. Instead, their straightforward presentation of Castoro’s sweeping monochromes on masonite offered the sensation of a lost treasure receiving its long-overdue public celebration.

The Independent has cashed in, repeatedly, on the gamble of being snobby and unapproachable to their general audience. While this is, generally, rather reprehensible in both practice and principle in selling non-essential entities, the galleries and the artists who participate in The Independent simply don’t have time for small talk or pleasantries. When the world’s most respected curators, museum directors, collectors, and editors are all vying for one minute of attention, who needs to be nice? If you’re Peres Projects, Maureen Paley, Société Berlin, Michael Werner, White Columns, Gavin Brown’s enterprise, David Kordansky, or kaufmann repetto, “nice” is just one more unnecessary hindrance to achieving glory during Armory Week.

Independent 2015 was conceived by Elizabeth Dee and Darren Flook, developed in conjunction with Matthew Higgs and Laura Mitterand. The fair was held from March 5th to March 8th at 548 West 22nd Street in New York City.