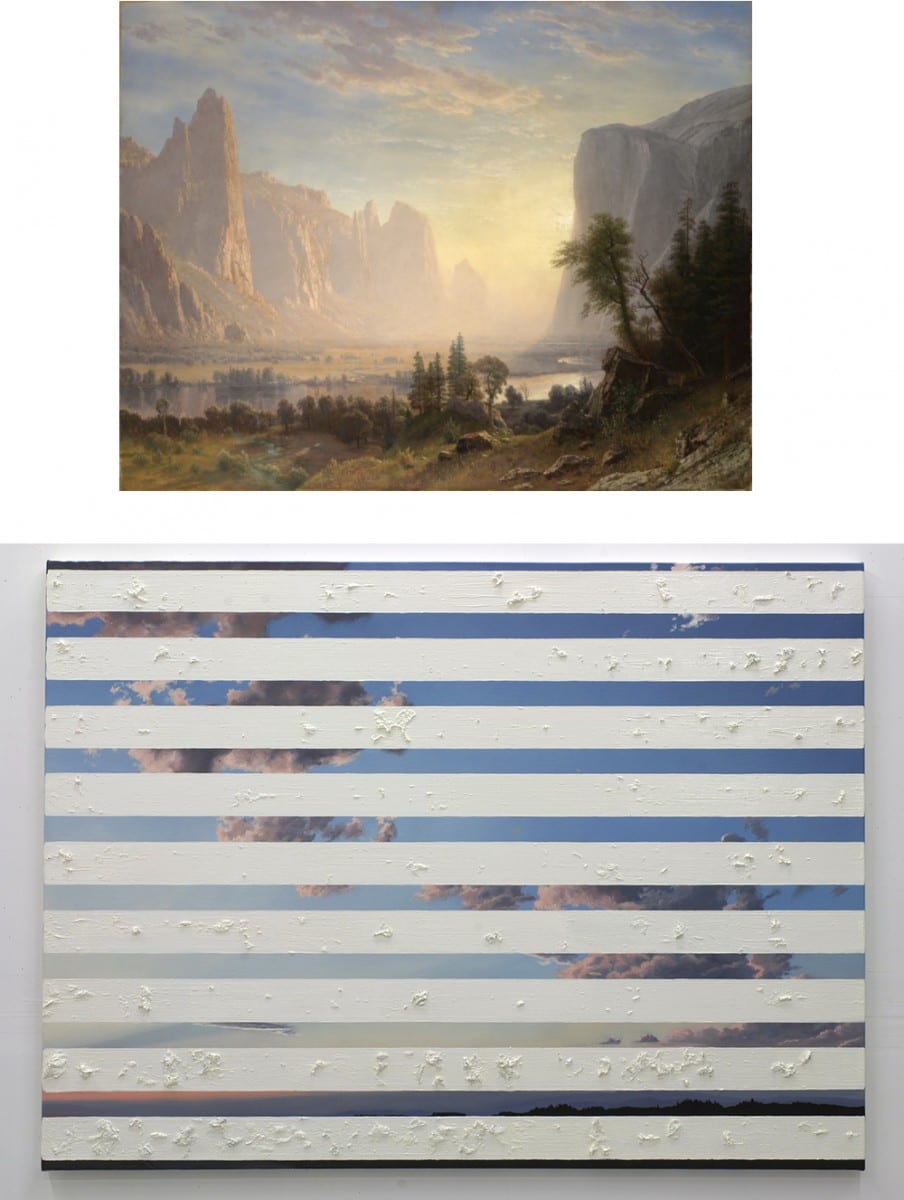

As an inspirational starting point, I have been thinking about the works of 19th Century landscape painters like Albert Bierstadt (see below) or Frederic Edwin Church, which depict the U.S. landscape as grand, transcendent, and even sublime. Painted from and for a European-American point of view, however, those works reflect and project a colonial gaze—one that advertises the abundance and promise of the American West and celebrates the ideology of “Manifest Destiny.” In doing so, those works encourage exploitation of the land and obscure the deception, displacement and murder of those already deeply connected to it. Recognizing this, even as I am drawn to those iconic paintings, I am troubled by them—the darkness in their light, the horror in their splendor.

My current body of work (titled Bounty, recently on view at VOLTA NY) explores these contradictions. In these paintings, I engage questions of light and dark, truth and fiction, substance and surface, reality and mythology. To address these concerns, I evoke the wide vistas, dramatic light, and stunning terrain of romantic landscape painting. However, I work to undermine that romanticism by layering images and materials and, for example, re-framing “heavenly” light and the color white as forces of darkness and portents of sorrow. My hope is that viewers are left wondering about what it is they are looking at—whether projected over, breaking through, covered up, or emerging from behind—and why.

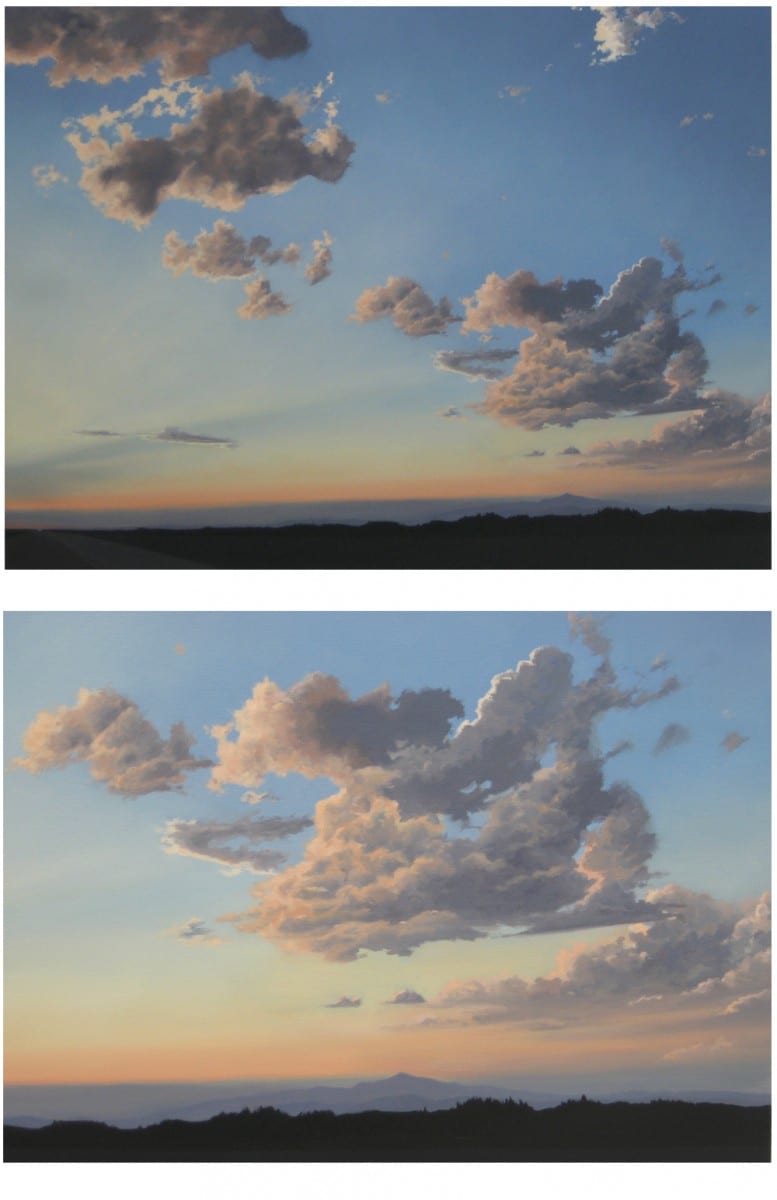

Below are a few images of recent paintings, as well as some in-progress pictures that I hope provide a window into my process. I chose these paintings/processes to highlight the different methods I use to integrate imagery and materials. The constant aspect of my process is that I work from my own photographs or photo collages that I have compiled over ten years of driving around the southwestern United States. I usually project these source images onto my canvas to start the painting.

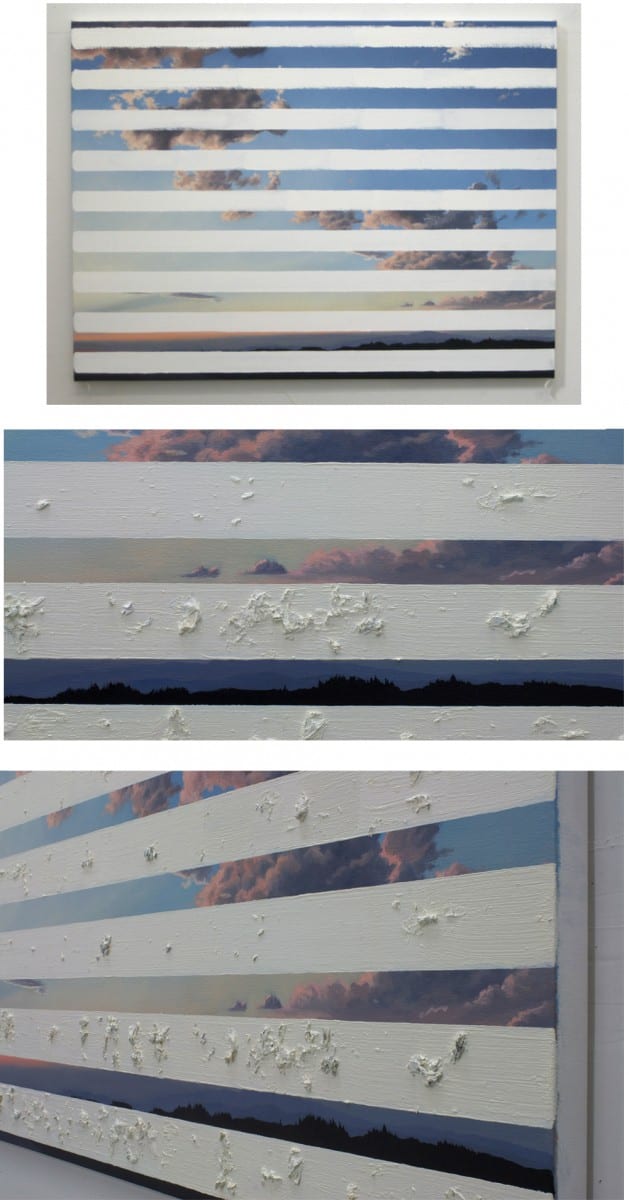

The first process I want to share is the making of Unveiled, which is pictured above in its finished state. I began the painting with a rather tightly-rendered painting that I would eventually cover up—or ‘deface’—with horizontal bars of chunky, white paint. Below you see an image of the whole painting, and then a detail of the bottom right, from just before I added the white strokes.

I believe that finding the right process is really important for each painting, and for this one, I thought I should be really invested in the romantic representation but also keeping in mind that eventually it would covered up. Perhaps this seems like over-thinking, but I imagined that it would heighten the tension of the final product if I heightened the tension in the making of the piece— feeling regret at “losing” the pretty sunset landscape. Even though I knew about half of the painting would be covered, I did not want to take a shortcut by only rendering the areas that would end up being seen.

After I “completed” the naturalistic representation, I took a large brush and lathered it up with thick, white paint, and made long horizontal strokes across the face of the painting. Below you see an image after the first stroke, and then after subsequent strokes made with added texture. The final product was some mixture of coming to terms with my ambivalence for those 19th-century paintings—wanting to evoke their beauty but also deny that romanticism.

I added texture to those horizontal strokes by mixing dried paint scraps into the white paint. This process is now typical for me, I collect the dried-up paint from my glass palette and then I re-apply it to the canvas. These particular chunks of paint were a myriad of colors, but all ended up being enveloped by the white paint.

By juxtaposing imagery and materials like this, I was trying to make the color white look ugly and obstruct the romantic landscape, preventing a viewer from being fully immersed in it. The appreciation of the the landscape would be incomplete if it was only the romantic painting, which in itself could be thought of as covering up or “glossing over” the European invasion’s ugly history. I hope viewers wonder what is being unveiled—the landscape, or the white blanketing/intrusion, and what implications it arises.

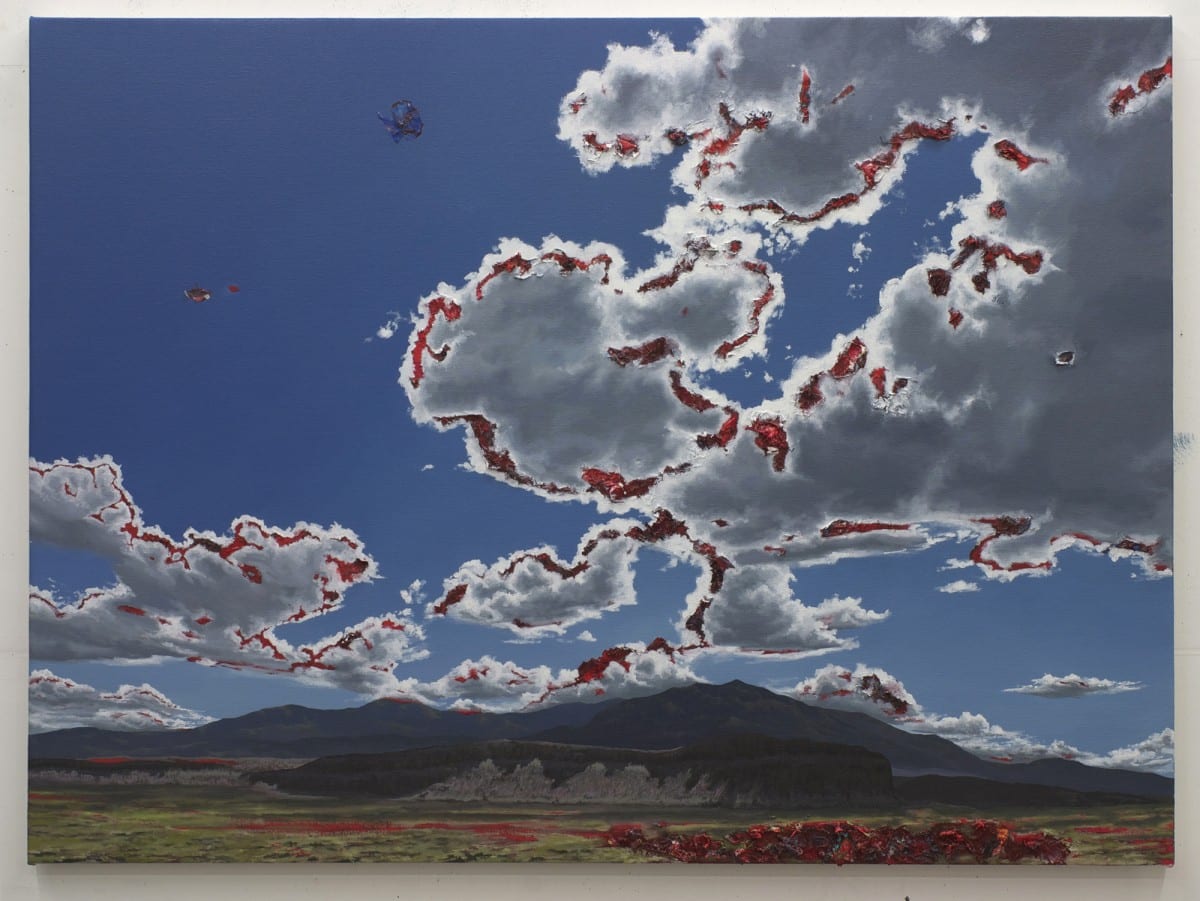

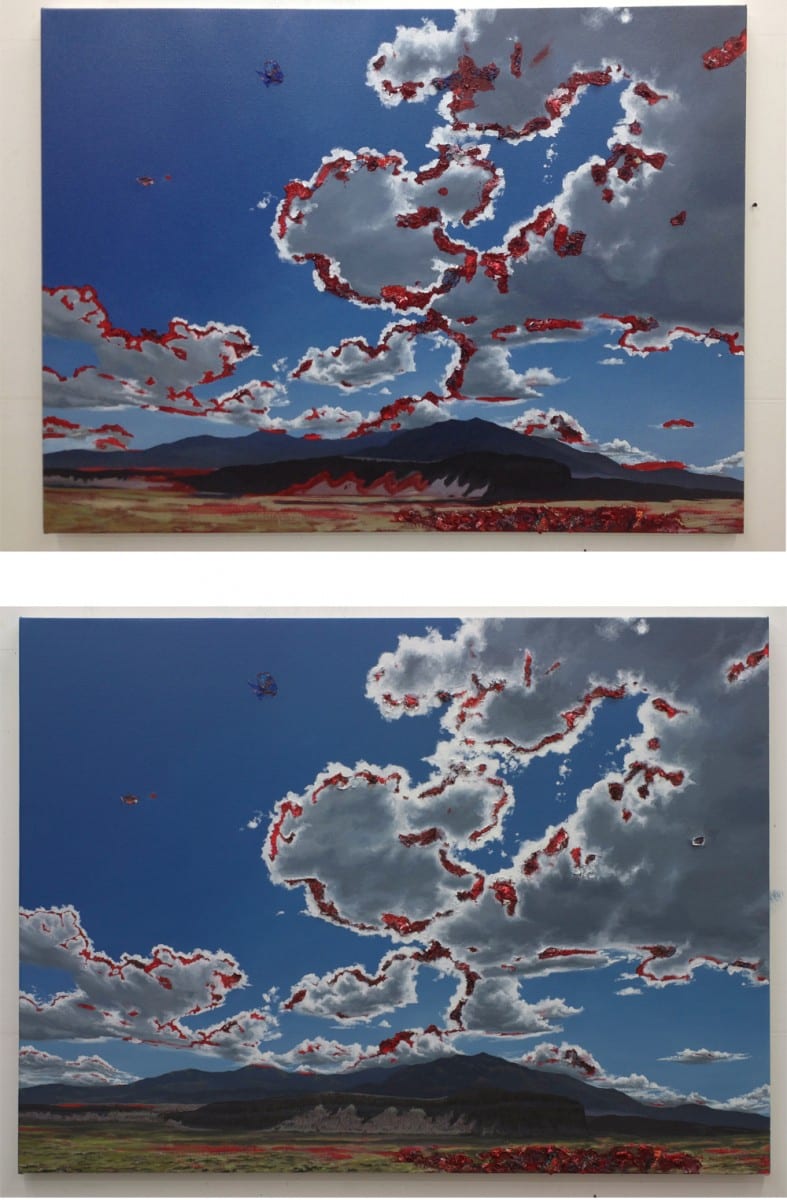

With the two paintings pictured below, I worked in the opposite order: first I laid down a blood-red wash, and soaked multicolored paint scraps in red and let that dry as an underlayer. After, I painted a representational landscape over that craggily foundation, but allowed the paint scraps to poke through the imagery and reveal themselves more toward the bottom of the canvas. With this order of operations, I imagined the representation as a literal and metaphorical cover-up of something rougher, uglier, with darker associations.

Legacy was made by interweaving representational painting with more abstract elements. Once again, I started with a red-colored ground, but in this work I knew I wanted the chunkier elements to seem like wounds so I coated all the paint scraps in red (if they weren’t red to begin with). I also knew I wanted those scraps to appear in the composition where the brightest whites would appear in the clouds, or where the sunlight would most strongly hit the ground. I began painting the representation of the landscape (from a collage of two photographs I took in New Mexico) and placed the red paint scraps accordingly.

In the process of creating Legacy, I had to paint and re-work the areas where the image and the crustier, three-dimensional paint meet. I wanted the red in the clouds to seem as if they are emerging from the whitest areas. In those locations and the lower right, I also painted on top of the scraps in various shades of red to give them a sense of glow, or being illuminated.

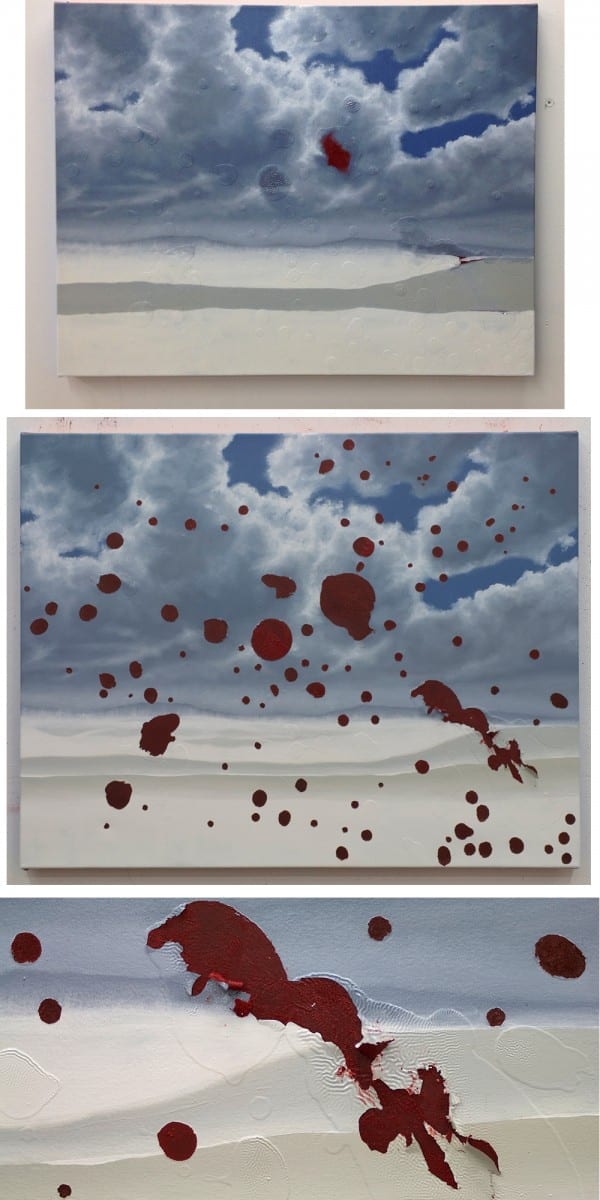

The last process I want to share is for the painting Pox. In an effort to create associations about the painting and the landscape as being living bodies, I chose to paint in a way that would emphasize its surface as actual skin. As with many of the paintings in this series, in this piece I portray the landscape as being sick, or that some invasive force is infecting it.

To start I laid down a dark red layer of color. After letting that dry, I created circular pools of brighter red. The glossiness and level of viscosity of these bubble-like pools comes from alkyd resin added to the oil color.

Next, I painted a landscape. You can see raised bumps created by those red bubbles, seemingly lying underneath the landscape. Once the landscape reached the level of naturalism I wanted, I cut and peeled away the raised bubble areas with a palette knife, revealing the red from underneath.

The site depicted is the rolling sand dunes in White Sands National Monument, New Mexico. I have painted White Sands several times because of its formal and symbolic value. As part of the National Parks system, the site aims to bring visitors to the area to experience its unique status as the largest field of gypsum sand dunes in the world. On a sunny day walking through this stark, white landscape, the brightness can be blinding.

The park is located within the boundaries of the White Sands Missile Range, an area used for missile and bomb testing, including the Trinity Site—site of the detonation of the first atomic weapon. By combining a representation with this specific kind of pockmarks, I hope to create associations about this landscape tinged with an undercurrent of conquest and violence, sickness and plague.

Featured image: Chris Barnard, Legacy, oil on canvas, 40″ x 54″, 2014

All images taken by the artist. Images © of the artist and Luis de Jesus Los Angeles