In my work I am constantly wandering, seeking form echoes, contrasting ideas– from the biological to the mechanical. Spaces, scale and meaning can shift within moments and within centimeters on the canvas. For better or worse, as my brain moves between thoughts, I follow them with paint and bits of collage. My works are a record of that shifting. They are attempts to gather everything–to relate every possible form to every other possible form.

Mined Land is made of four adjoined panels. Because I have horror vacui, I began with two panels that I’d painted in 2003. I sanded them down, leaving only traces of the former imagery and color. After a month working on them paired in a long horizontal format, I decided to add the two lower panels. This turned a sprawling mountainscape into a giant egg-shaped island. Dozens of problems, compositional challenges and visual hurdles emerged. What was this island, and how could I get off it? I didn’t want it to be marooned, dead center in this vast space. Bridges needed to be build, escape routes created, cities erected, vegetation planted. Also, I began to burrow into it and to carve out caves and crevices. The island became more solid, while becoming porous, skeletal, almost spongelike. I suspect it won’t be long before it collapses in on itself.

As I’ve described, my studio is filled with antique paper and old information. On my shelves, you’ll find sections on human anatomy, botany, engineering, cell structure, architecture, mammals and aquatic life. You’ll find a 1940’s catalog of practical joke toys, player piano scrolls, piles of topographic maps, a 1950’s hardware store catalog that is two feet thick. These books and manuals are filled with visual information, much of it obsolete, translated by human hands and minds before there were cameras to capture the outer appearance of things. (While I value what technology has brought to us— electron microscope and satellite images certainly inform my work– I think something has been lost with the ubiquity of modern photo-reproduction). I mine these sources for imagery, forms elegantly or clunkily drawn that call out to other forms across category and function. This is the magic for me. Connecting forms—or rather, when it works, it feels more like discovering the connections that were already there.

During the six months that I was working on Mined Land ancient artworks were destroyed in the Middle East, toxic chemicals were spilled into waterways (by “Freedom” Industries mining company), debates raged around climate change, Fracking, oil drilling. New species were placed on the endangered list. It’s not that I set out to make a statement or comment on the human disconnect with nature, but it emerges anyway. It’s much like the way I set out to find tree roots and end up with rusting machinery.

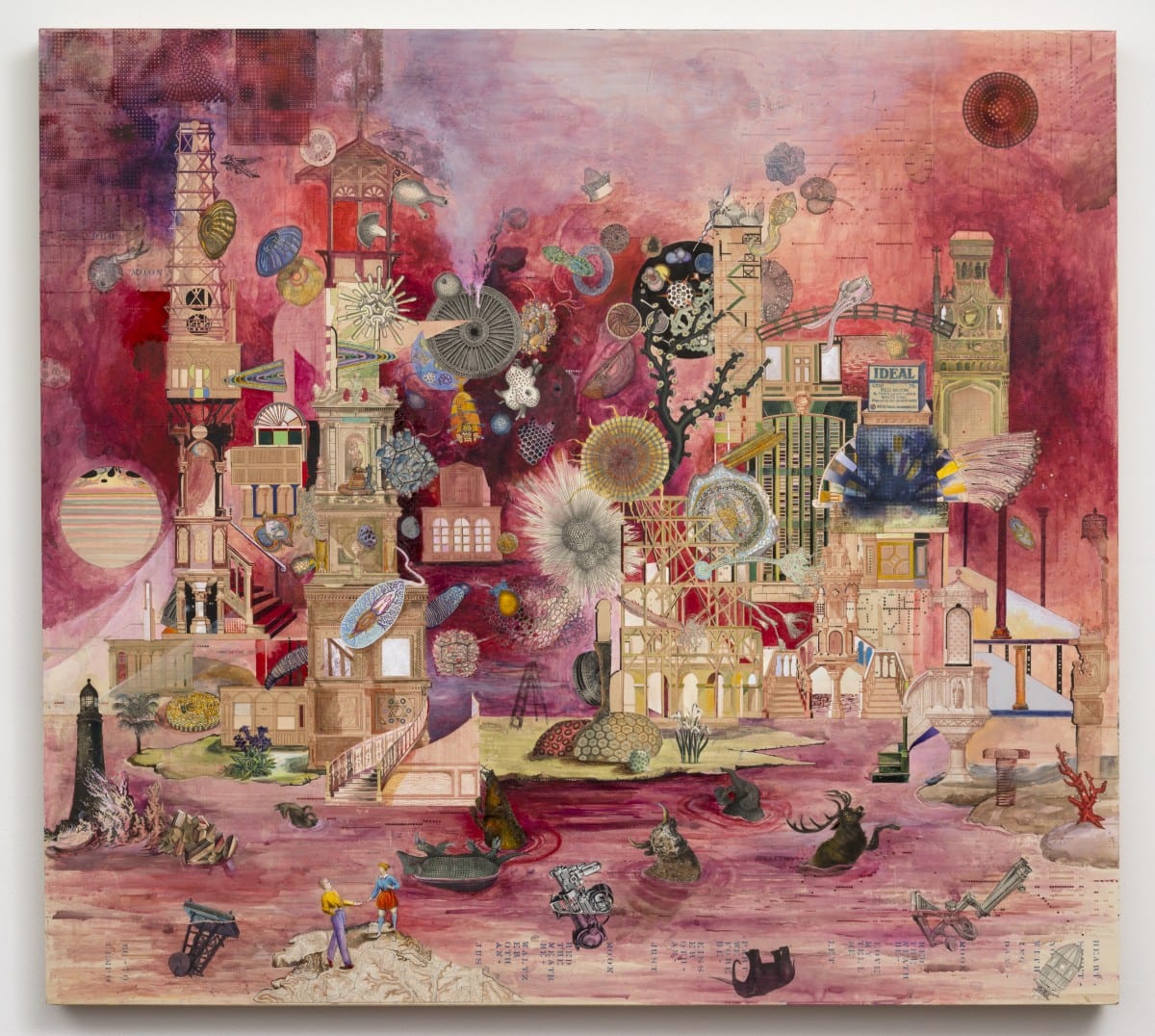

Red Moon was executed in a solid stretch of 12 15-hour workdays. I always work on multiple panels simultaneously, but with Red Moon I became obsessed. Call it my ‘minimalist’ piece. I forced myself to work with a reduced palette and I clung to an architectural structure broken only by explosions of radiolaria and plant cells. The foundation for Red Moon is a layer of old yellowed player piano scrolls. The rhythms of the music literally punctuate (and puncture) the field with dots and dashes. Scraps of the lyrics to the song Red Moon appear on the surface. Toward the end, I even gave in to the romance— “just another waltz beneath the red moon. Just another kiss before we part”— and I added a pair of lovers at the bottom, dwarfed by the red chaos all around them.

There are two pieces that revolve around a 14-foot scroll drawing I began at the Art Omi residency last summer: The scroll itself (entitled “Sometimes we find a broken cup”) is displayed in a rustic pair of wooden boxes with antique cranking handles.

A 10-minute animation, which travels through the scroll scored by Erik Satre, is screened nearby. My graphite drawings have always been a mystery to me. With the graphites, I employ a long horizontal format, and this time the format was pushed to an extreme. I always begin with an empty mind and with no compositional idea or thematic scheme. I begin on the left side and rubbing lightly with a number 4 pencil, I see what emerges over time, periodically adding antique engraving collage elements, which I disguise in the graphite world.

With this scroll, a hazy narrative emerged, triggered by a little figure clipped from a 19th-century medical textbook on diseases and deformities. This tiny engraving depicts a little boy staring out at us and lifting his robe to reveal a twisted spine and a leg brace. It’s a heart-breaking image to me. I imagine this boy in a hospital in 1800, patiently posing for an artist who sketched him faithfully and then took the image to the plate for engraving. This child was not represented for the sake of art; it was a utilitarian act. I’m fascinated by old information like this. I have hundreds of antique books, diagrams, maps and catalogs in my studio. They are filled with visual information, much of it obsolete, translated by human hands and minds before there were cameras to capture the outer appearance of things.

Anyway, this little figure set a somber tone for the scroll and triggered other images of disfiguration: a legless elephant, fences made of bones, a burning house, a baker at an oven creating a prosthetic limb. As one moves across the scroll through time, images echo. We move between cellular scale and aerial landscape. Animals are found and lost. Plants germinate, grow and wither. The accompanying animated film was a six-month-long project in which I pan through the scroll and add movement, new figures, and more obscure narratives. The music and sounds created by Satre add layers of atmosphere that weave the journey into a whole. As with all of my works, my intention is to be incredibly specific without prescribing meaning. The viewers bring that into the equation.

All images © of Josh Dorman and Ryan Lee Gallery