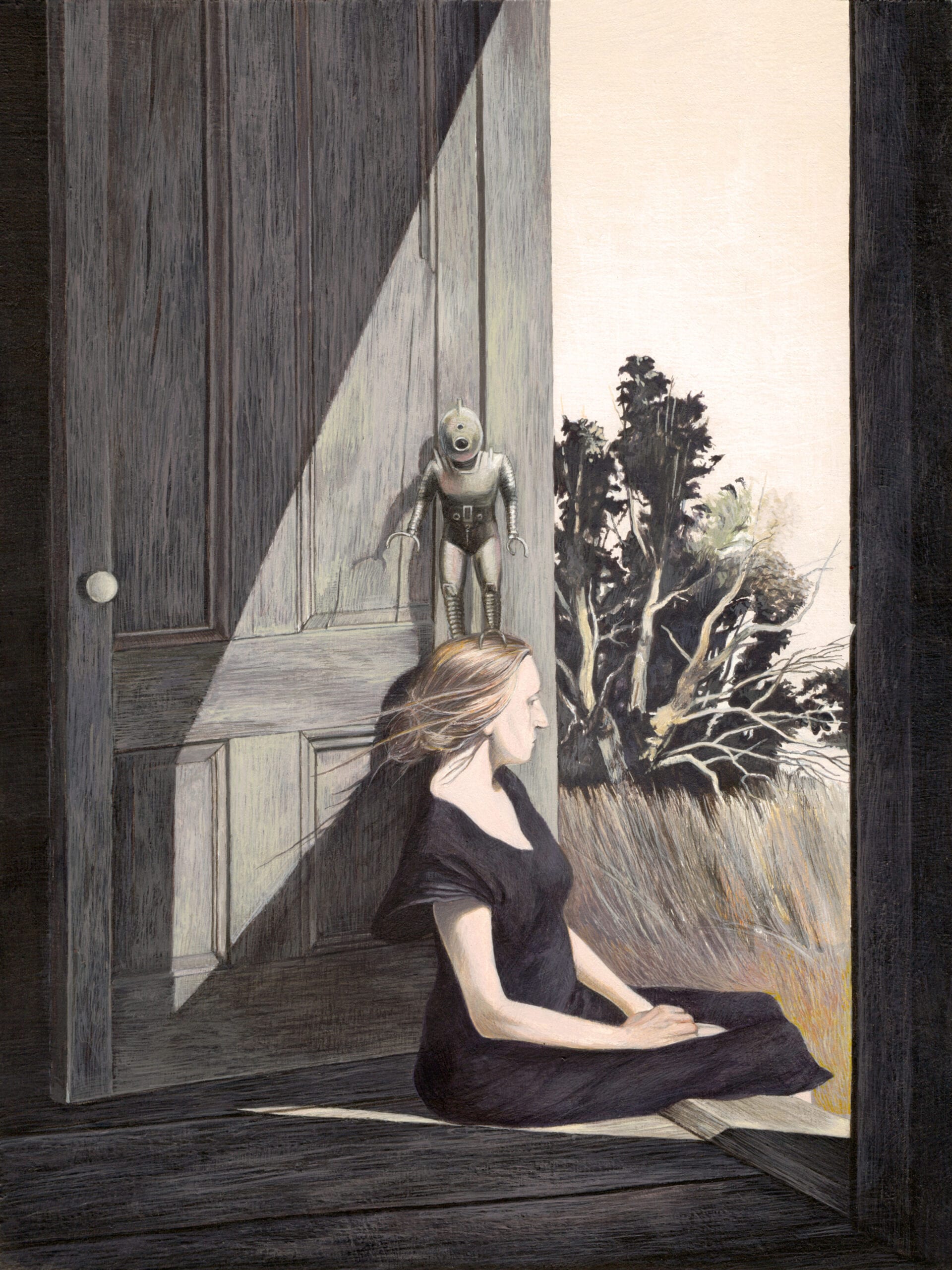

In this piece, Andrew Wyeth’s model Christina Olson—who suffered from a degenerative muscular disorder in real life—sits, inactively staring out onto the soft landscape, finding solace on the boundary between the internal and the external. Because of Olson’s dormancy and comfort in the serenity of this moment, technology serves little purpose. The robot is given no instructions and has nothing to do but wait; it’s as helpless as an infant.

While the woman rests in the doorway, potentially powerless outside of the home without mechanical aids, the character of technology loiters over her – powerless without her direction.

[columns_row width=”third”]

[column]

[/column]

[column]

[/column]

[column]

[/column]

[/columns_row]

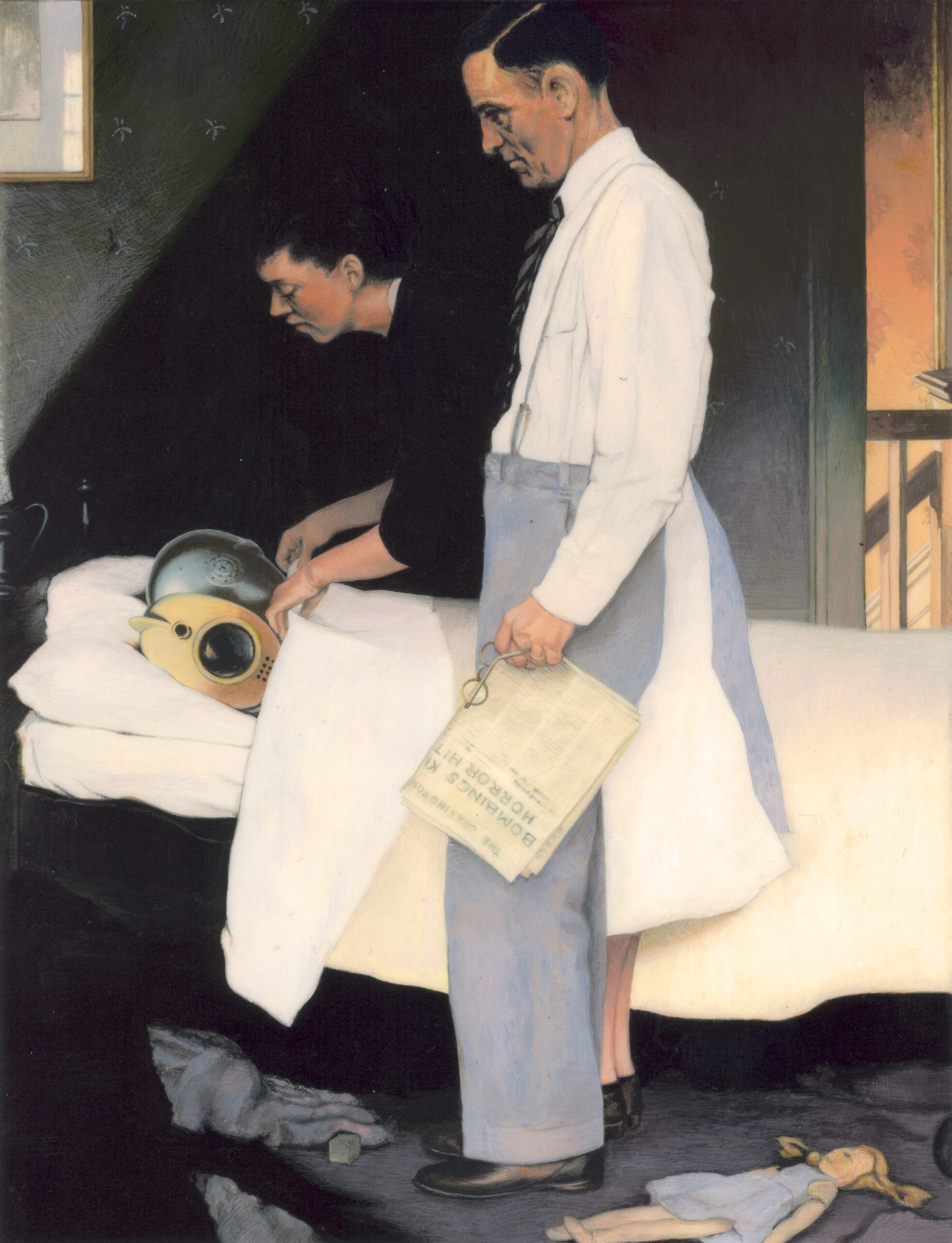

It’s no secret that we cherish our technology. Our domestic spaces – even our children’s bedrooms – are heavily populated with small electronics with which we’ve fallen in love, thanks in part to the joy and, quite often, the escape they offer us. This piece has its foundation in that idea, in that intense appreciation and acceptance of our technology, with an eye toward the consequences of such relationships.

Two robots have replaced the two children who originally populated Rockwell’s painting, while the actions of the parents remain equally as devotional as they were in the source image. As the adults put their devices to bed, they express an acceptance of technology, an acceptance devoid of reluctance. Yet the absurdity of their actions highlights the inevitable shortcomings of their predicament – technology can’t possibly replace the warmth and adoration that exists between parents and children.

Stated another way, the wholehearted acceptance implied by the phrase “put it to bed” coexists with a predictable deficiency of kinship that may eventually require us to “let it [technology] rest.”

[columns_row width=”third”]

[column]

[/column]

[column]

[/column]

[column]

[/column]

[/columns_row]

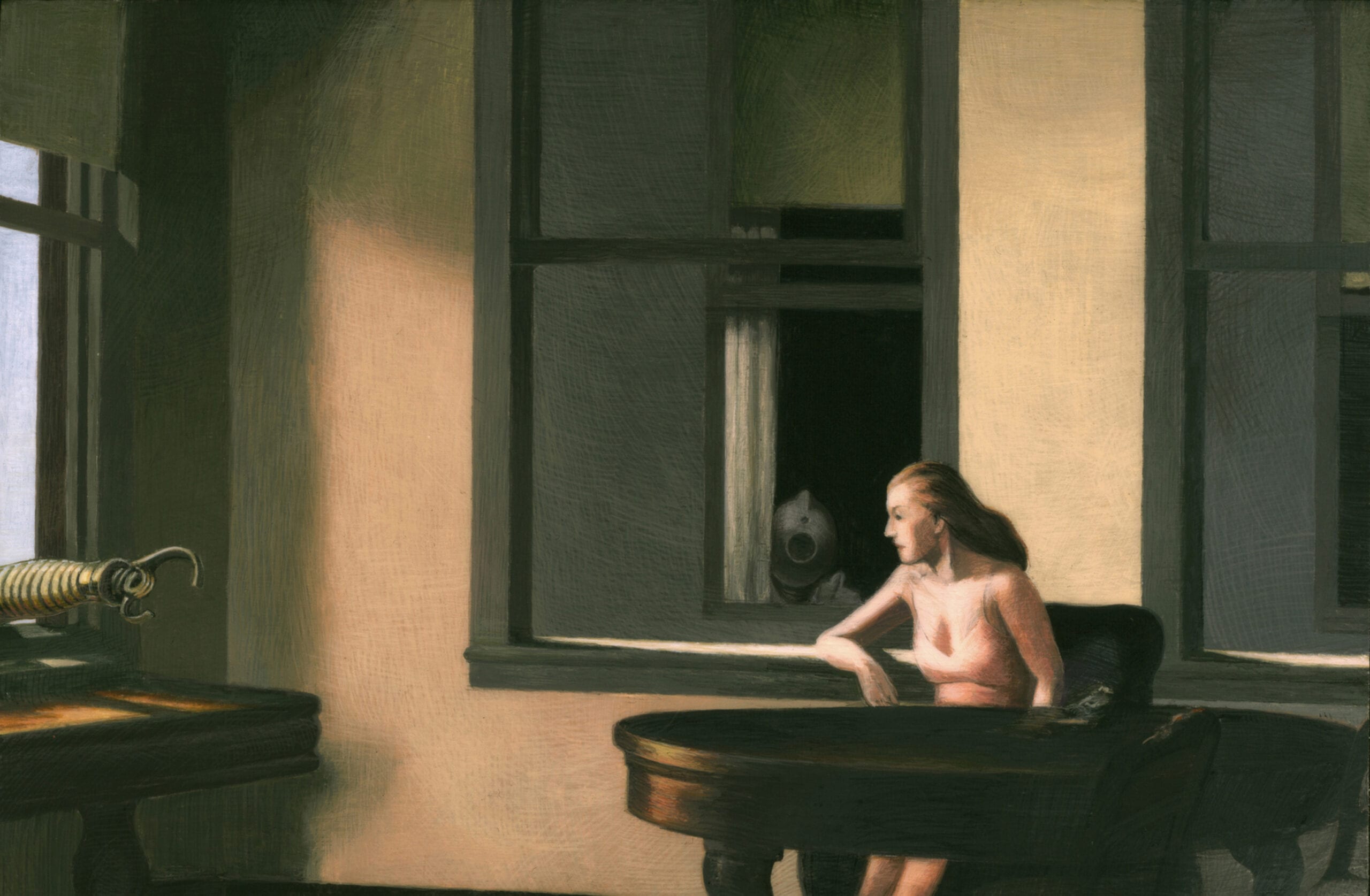

Since the dawn of the Internet Age, there have been viruses, scams, and hidden codes that have existed only in the background of our digital activities. Unless we’re programmers ourselves, we happily go about our business, ignorant of the underlying depth of digital space. Every once in a while, I enjoy contemplating the layers of our technology (and, as a result, its surveillance potentials – i.e. who gets to see our activity, who’s responsible for setting the parameters in which we get to function, and how our choices impact the larger systems involved).

In this work, Valigursky’s robot lurks in the corners of a neighboring building, watching the female character as she focuses on the more obvious encroaching claw. The woman doesn’t share our awareness of the robot’s presence, but it may serve to highlight our own vantage point as voyeurs. We recognize ourselves staring at her as intently as technology is, but at least he’s had the decency to reveal (at least a part of) himself.

[columns_row width=”third”]

[column]

[/column]

[column]

[/column]

[column]

[/column]

[/columns_row]

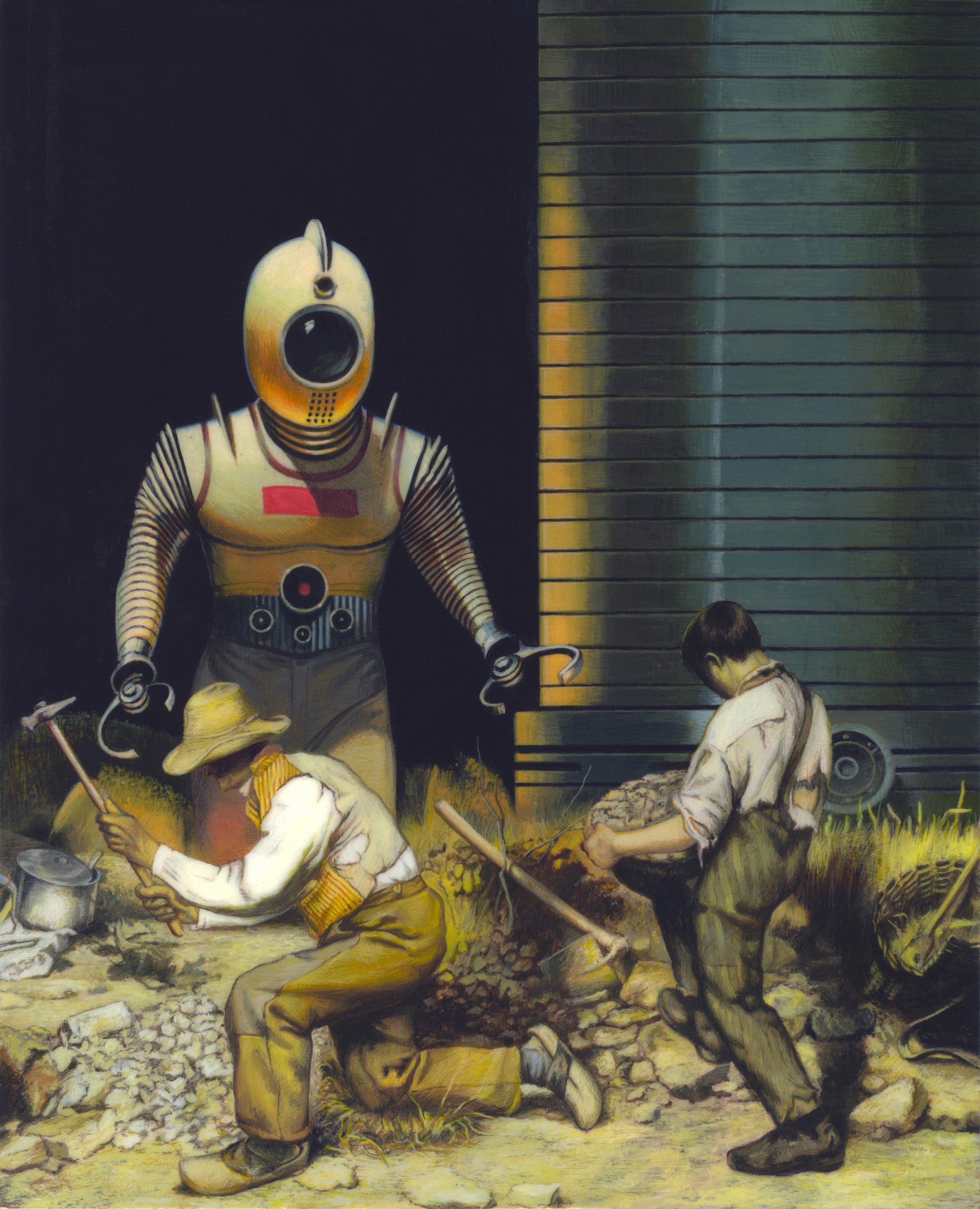

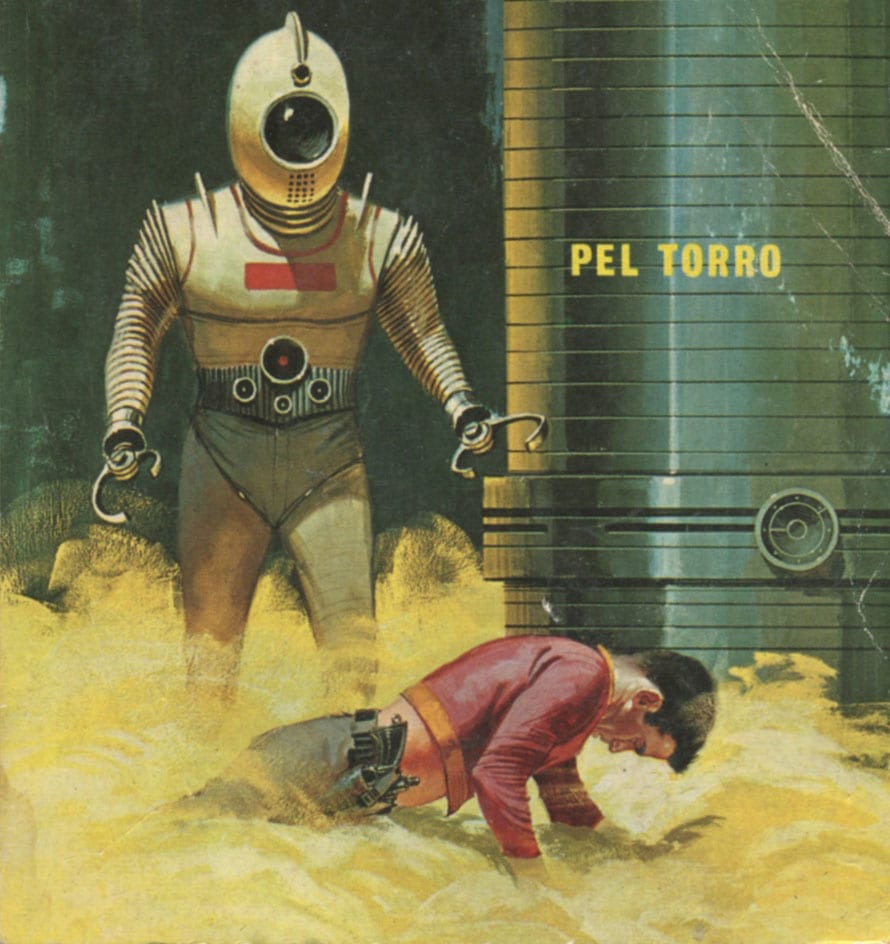

In the summer of 2013, we were horrified to find out that the NSA was spying on us, and for months, the airwaves were filled with a steady chorus of wrath directed at the government. But people forgot something in their rush to anger – namely, that we’d have been as upset if someone had instead revealed that our government didn’t have the technology necessary to fulfill the expectations James Bond movies had established in our collective mind 50 years ago.

This conflicted relationship between humans and technology quickly became the content I needed to wrestle with throughout the Jetsam series, of which this was the first piece produced.

In this image, I’ve interpreted this duality by presenting the robot as both savior and dictator. From one perspective, he offers a potential lightening of the load for Corbet’s peasants – here’s a machine to do this absurdly strenuous work for you! From another angle, however, he becomes the cause of their plight – overbearing, forcing the men to manually complete his backbreaking commands. The humanity to which these men belong has progressed enough to invent robot aids, and has then become minion to its innovations simultaneously.

[columns_row width=”fourth”]

[column]

[/column]

[column]

[/column]

[column]

[/column]

[column]

[/column]

[/columns_row]

Digital technology and culture rely on a built-in dissatisfaction in order to progress. The science fiction that once promised us jet packs and flying cars has been replaced by persuasive speculation about the newest features that’ll define upcoming devices and services (think “I heard the next iPhone will have a bigger screen.” or “Pretty soon smart watches and Google Glasses will replace the tablet.”) And, stereotypically, these progressive challenges to the technological status quo are fueled by younger generations, generations who’ve been raised to expect products to become obsolete every few years.

The narrative of David and Goliath has been used here to illuminate this challenge. Rather than pinpoint the differences in stature between the characters that define the original story, I’m relying on David’s youth to serve as an opponent to a dated technology. In the timeline of the robot’s life, we’re seeing him older than ever before and, as a result, the prey of a discontent operator.

A bit of a Catch-22 – A culture expecting planned obsolescence creates technology unable to survive, in order to sustain its own evolution.

[columns_row width=”third”]

[column]

[/column]

[column]

[/column]

[column]

[/column]

[/columns_row]

Images © of the artist and Jonathan Ferrara Gallery