I am not trained as a potter. I have taken lots of classes over the years, but always for pleasure and never as a real ceramics student. My training is in architecture, in the context of art and design school, so I do not have the expertise to know where “traditional techniques” and “experimental techniques” begin or end. One of the most attractive things about working with clay is the variability of reactions one can get from the most simple materials when combined with heat. The smallest changes in routine or process alter things radically, forget about changing clays and glazes. It could be something as simple as what the weather is like on the days that you fire, the amount of water in a glaze, or the amount of time between the coats of a glaze, even the speed of a firing. There is so much at play. It is fantastically exciting and I love the element of risk and gambling in it. In my practice there is no attempt at repeating the same thing over and over, instead it is more about pushing the same thing into new directions.

Installation Magazine: When did your interest in ceramics begin?

Adam Silverman: My interest in ceramics began as a “schoolboy” hobby when I was in Middle school and continued on through High school and college.

When did you realize that it was a vocation you wanted to pursue full time?

In 2001, after many years of being a “hobby” potter with increasing intensity, interest and improving results, and after my personal life shifted post 9/11, followed by a divorce and the arrival of my two young daughters, I decided to attend Alfred University in the summer of 2002. I took the course with the intent of deciding, at the end of the program, whether I would become a professional potter (that is, if a summer of hard, full-time studio work in a serious context felt good and the responses were right) or whether I would finally put the professional potter fantasy to rest and just continue as a hobbyist without the distracting fantasy of “going pro.”

How has Heath Ceramics influenced your artistic practice?

Being part of Heath for the last five years has been great and influential in many ways. Having the security of being part of a company has allowed me to explore and be more experimental than I may have been able to if I was still on my own. Heath has a history and aesthetic that I relate well with and it feels good and easy to be a part of that aesthetic now. My partners (and bosses) Cathy and Robin, who bought the company from Edith Heath ten years ago, have a really great vision of what a design-focused American manufacturer can and should be in the 21st century and they are committed to making their vision a reality.

Your exhibition Clay and Space opens at the Laguna Art Museum on October 27 and runs through January 19, 2014. The body of work reflects the environment of Laguna. How did the process differ from your traditional studio practice?

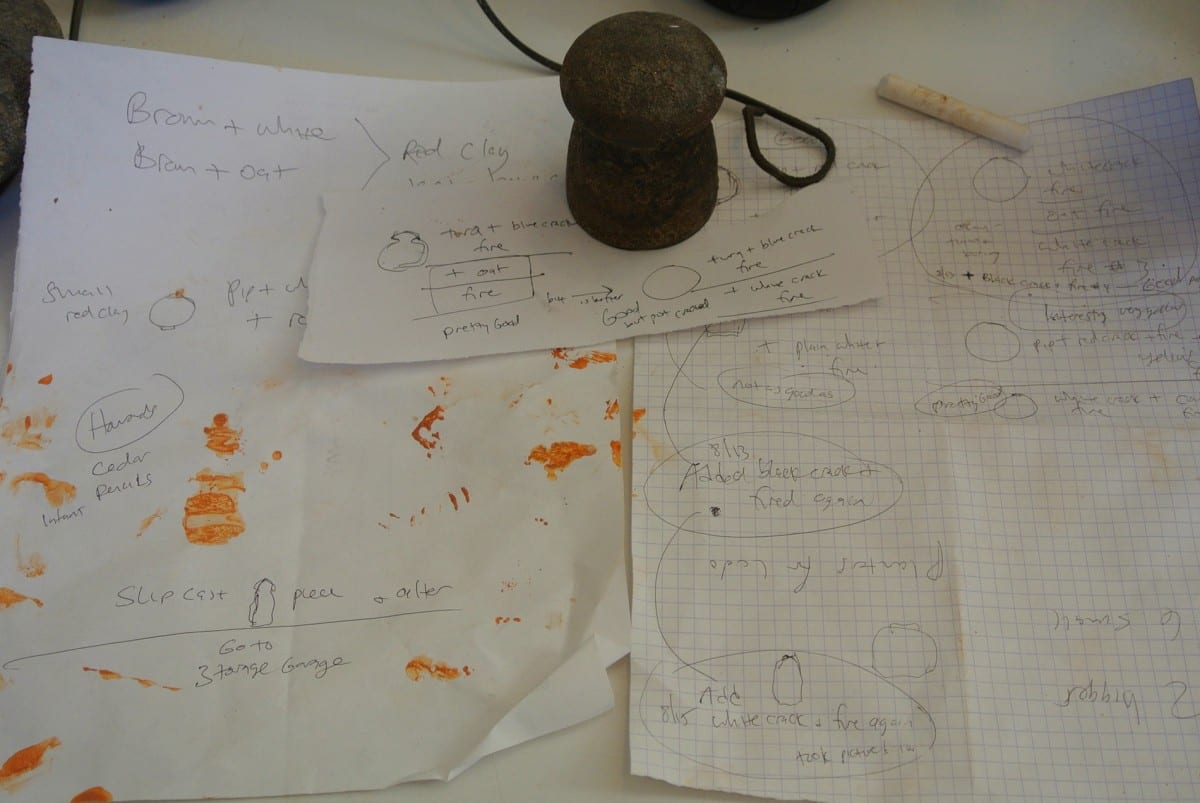

In my main studio, my usual practice requires electric kilns, so they provide heat but no atmosphere that would contribute to the appearance of the pots. The process of making a pot in the studio is like this: I think about what I want to make, get the appropriate amount of clay, and throw the pot on the wheel. I let the pot dry until it’s leather-hard and then I flip it and trim the bottom of the pot and foot. I let the pot become bone dry and then bisque-fire the pot in the kiln. The bisque-firing is done at a lower temperature than the final glaze firings. The purpose of the bisque-firing is to ensure that the pot is strong enough to handle and to be glazed, but to still be able to absorb moisture. Finally the pot is glazed and fired. The pots fired on the beach in Laguna go through the same processes, bisque firing. Some of them have slip (a liquid clay) brushed or hand-rubbed onto the pots before they are bisque fired. This slip, however, is made of clay from Laguna Canyon. The beach pots themselves are not glazed, but I add other things to the fire to enhance the atmosphere so that the fire provides more for them to react to. Each time I fired, there were different conditions and different things in the blaze, so that each piece from the beach features subtle differences.

The exhibition features elements of sand, salt water and the beach is used as a destination to fire the pieces. What inspired the decision to work with the elements?

The museum’s director, Malcolm Warner, encouraged me to push toward new territory for the show. Since I work in the middle of Los Angeles in a very urban studio, the idea of firing pots on the beach was an easy and obvious counterpoint to my usual practice. I have done different kinds of firing in different places over the years, but never a simple pit firing on the beach. Once that idea was hatched, I started gathering local materials to burn as fuel in the fire, as well as collecting local materials that could influence the environment in the fire and potentially affect the appearance of the pots. I used several different bodies from Laguna clay, then added slip made from local clay found in the Canyon onto some of the pots. I made salt from water taken from the beach, and collected driftwood, seaweed, and even kindling from the Canyon to burn. I was also able to find a local firewood supplier who makes his logs from local wood and tree-trimmers. So the fires were all burning materials from Laguna. In the end I am not sure if that makes any physical difference to the results, but I do think that it certainly does make a philosophical one.

What were the greatest challenges that were presented working this way? Did you feel like you had less control over the process as opposed to working in the studio environment?

The challenges were also the pleasures. Spending many hours, days, and evenings on the beach in Laguna tending a bonfire was hot, smoky, and super fun. There was much less control over the firing process than I have in my studio, but that was by design, and as long as I embrace the results as being radically different from my usual aesthetic, then I am happy with it. In the end most of my work is about the process, the materials, and the methods of their making. The pots are records of the process in which they are made, so the beach pots are perfect examples of that.

Walk me through the process of creating the works that are included in the Laguna exhibition. What is the process from start to finish? Does it begin with a sketch?

The show itself and the four different galleries and their layouts were designed through drawing, model building, and many site visits, very much in the way that an architect would design a show. In this case the only exception is that the work and the show were being made simultaneously, the chicken and egg thing. There were some eggs already done, but many were being made as the chicken was too. As for the works in the show themselves, I have described everything except the sculptures. The sculptures in gallery number three are clay tops on concrete bases. They are a continuation, a next step, of sculptures that I made for a show at Edward Cella’s Gallery in Los Angeles in 2012. In the case of these sculptures, the glazes are limited to blues and whites, in a not-so-subtle acknowledgement to the museum’s location on the bluff in Laguna, where the sea, sky, and land meet. The bases are cases of concrete in my studio. We used wood lathe in the form work to give them deliberate textures that gives both dimension and connection between art and the techniques used in Architecture and construction.

The museum experience greatly influences the way a body of work is experienced. How did you develop the layout of the exhibition? What are your hopes for the viewer as they navigate through the space?

In this show I am using four smallish galleries, so there is an almost domestic scale to the show, which I like. I also like the way in which the layout afforded the opportunity to make four distinct (though I hope related) installations. The viewer will enter the lobby and immediately see into the first gallery, then once they move further into the lobby they will align in an axis with three galleries in a row, seeing through the first and second into the third. There is a spatial scenario set up between the three galleries that is meant to pull you into the first, then the second and finally the third, moving you around each in specific ways. The first gallery has one wall of pots made over the last five years or so, about 18-20 pots, installed in plexiglass boxes mounted onto the wall. Each box is all plexi, on all six sides, so you can see each pot in a unique way. If the pot has an especially nice foot and bottom, it may be installed eight feet high on the wall so that you can walk under it and look up, or if the top on a pot is of particular interest, then the box may be installed one foot off the floor so that you can look down onto the top. All of the pots are composed on the wall into a group composition or constellation, so that they have another appearance and set of relationships as a group.

The second gallery has two brick rooms or chambers built in them, each about 6’ x 9.5’ in diameter. They are built from old bricks that come from decommissioned kilns that once made ceramic sewer pipes at mission clay. The chambers are large enough that one person at a time will go inside and view a group of the pots made on the beach in Laguna. Each brick room will hold between 15-20 pots.

The third gallery will have a circle of eight sculptures. The circle will be small enough to walk around, and should be (I think?) loose enough to walk within as well, so that you can see each sculpture on its own or feel them all as a group.

The fourth gallery is not on access with the first three, but is entered from the side of the third gallery, and it contains two video collaborative pieces and an accompanying audio piece. One piece was a collaboration with Lucas Michael in 2008, a great artist from New York. In the piece, I have an almost spherical pot covered in white lave glaze. Lucas filmed the piece slowly rotating. In the museum, the original white pot sits on a pedestal in the dark and a video of itself rotating is projected back onto the pot, giving it a very confusing and beautiful second surface. It looks like something is happening to it that you cannot understand, as if some mysterious material is pouring over it, or that it is in some strange sort of motion. The second video piece was made with David Kelley, a filmmaker in New York. It is a piece about Le Corbusier’s chapel in Ronchamp, France. In 1986 when David and I were both students at RISD, we visited Ronchamp with a film crew to make an ambitious documentary about the building. We used some of the footage shot in 1986 to make this piece. This was not a documentary, rather a piece that is meant to help the viewer experience the building through our eyes. This building is probably the single most influential piece of art in my life and my work as an artist.

In cinema the term auteur is used to describe a director who leaves an unmistakable mark on their work. I feel that your practice is no different. The finishes of your pieces feel like they’re living organisms and capture moments of nature as its evolving.

I have a very small number of glazes that I’ll use. I’ll make only a few per year and then introduce those to the rest of the glazes in the studio to see what they can do together. Most of the pots are fired many times with several glazes each time. There is often grinding of the surfaces between firings, and/or sometimes after the final firing. The whole thing is very rough, loose, messy and process-oriented. My only real goal is that the work feels right to me, that it feels like it somehow represents me, and that it isn’t too much like anything else people haven’t seen before. I hope that the pots are both of this moment, in this place, and at the same time that they could be from anywhere and anytime.

Your new book published by Rizzoli titled Adam Silverman: Ceramics does an incredible job of capturing the textures of your work. What surfaces inspire you most and have the greatest influence on your aesthetic?

I don’t know what surfaces influence my aesthetic, anything could, I guess. As long as it is expressive and interesting.

In what ways does the layout of the book represent the growth of your practice?

That’s another hard one. The layout of the book is the result of working very close with designer Tamotsu Yagi. Tamotsu had a very calm and firm influence on every aspect of the book. I am very lucky to have worked with him.

What are your hopes for the future of your practice? Do you want to explore new techniques or materials?

So far things have been evolving very naturally, and in a way it feels good, so I hope that continues. I am doing my first public art project next year on the corner of Santa Monica Blvd and Crescent Heights, which is very exciting. If that goes well, I think I’d like to do more of that work, but I also really like the scale and intimacy of making pots, so I imagine that will always be the foundation of what I do.

Adam Silverman’s exhibition Clay and Space will be on view at the Laguna Art Museum from October 27 through January 19, 2014.

Featured Image: Adam Silverman at Heath Ceramics ©Carly Moret

All images ©of the artist and Laguna Art Museum, all images of Adam Silverman at Heath Ceramic Studio ©Carly Moret