The paintings of Andy Moses possess an intense magnetism defined by a palette of hypnotic pearlescent hues. The solo exhibition Recent Works on view at William Turner Gallery presents large-scale circular, hexagonal, and concave wood panels treated with a skillful hand conducting colors like a synesthesia symphony. Oil and acrylic paint charge the surfaces, however, there is no evidence of a brushstroke. The brushless shapes feel inspired by the wonders of the cosmos and act as a portal transporting the viewer into an alternate time and space. The paintings assume a sculptural weight in that our relationship changes to them as we change- that is the distance and angle in which they are perceived creates variations of the form. The works have an alluring otherworldliness that brings into question our relationship to the mysteries of the galaxy and considers the alchemy of delicate surfaces.

In what ways did your environment growing up influence the themes that you now reflect on in your work?

I grew up across the street from the waves in the Santa Monica Canyon. I used to walk to the cliffside every night to see the sunset. Looking into that infinite space of the horizon it was never the same image. It was constantly changing and constantly fresh but there was something very stimulating about it because it was changing. It felt like you were looking at this kind of life force, so that was always kind of interesting to me growing up.

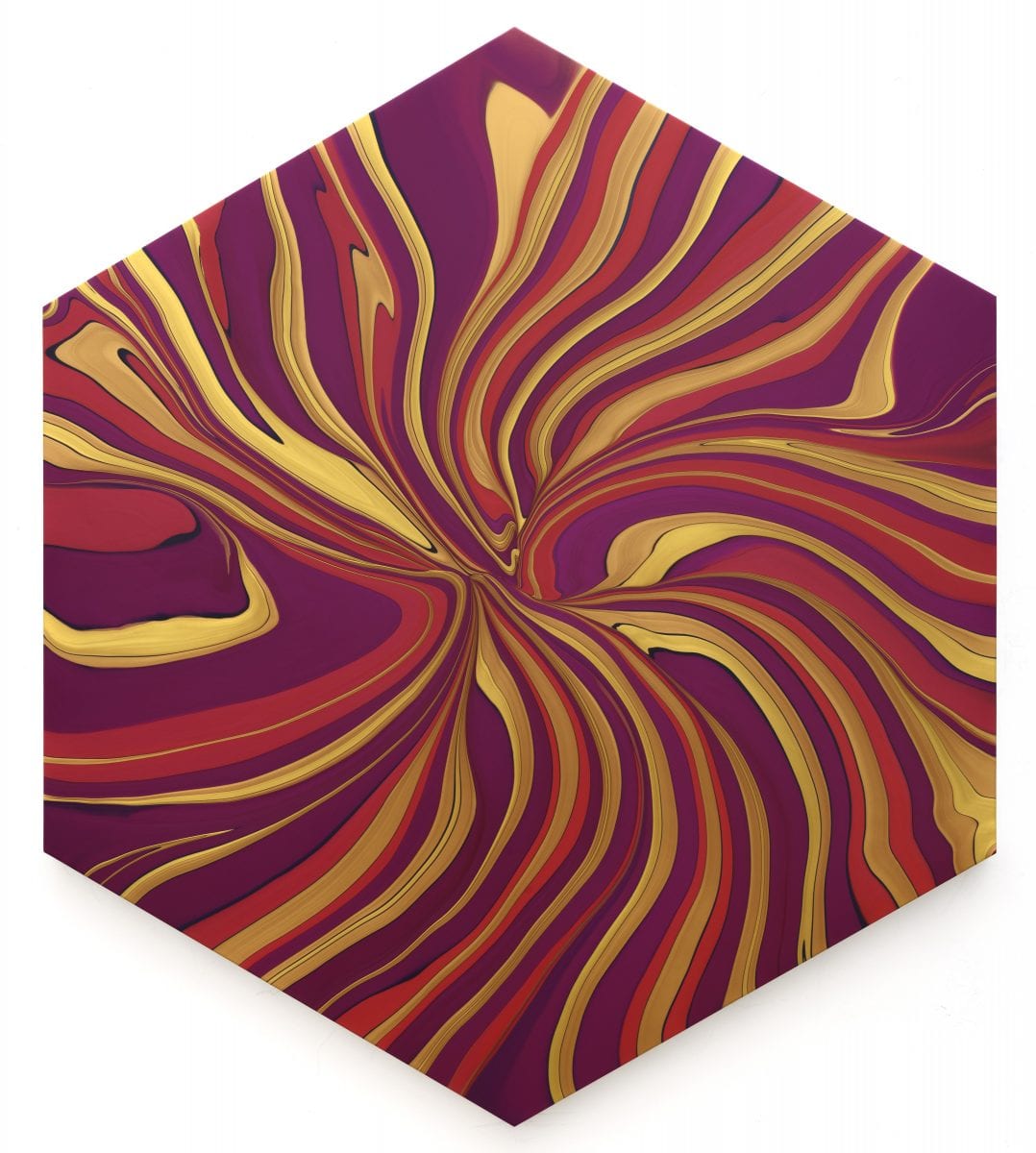

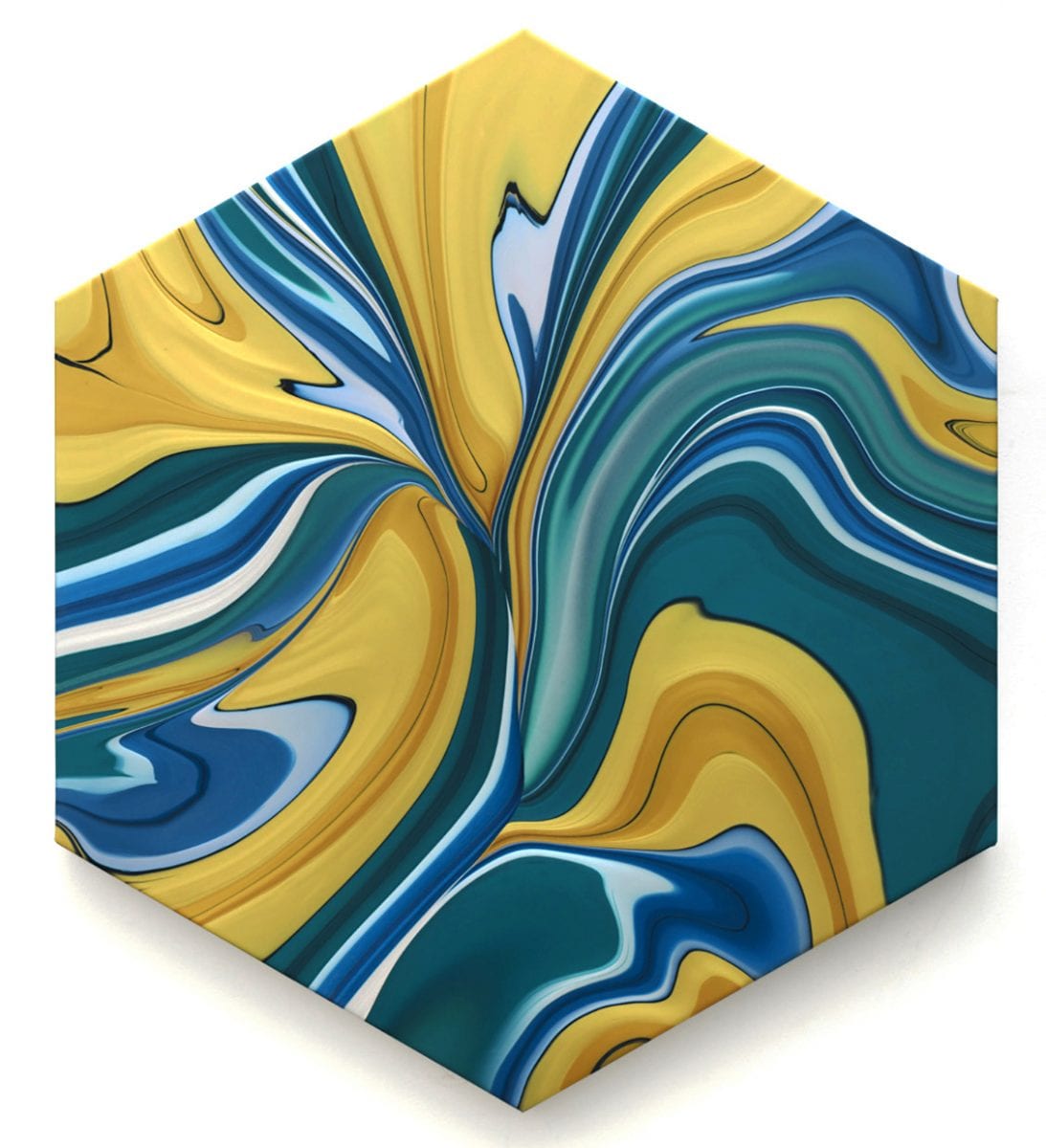

acrylic on canvas over hexagonal-shaped wood panel

78 x 67 in.

Photo by Alan Shaffer, courtesy William Turner Gallery

Artwork courtesy of Andy Moses

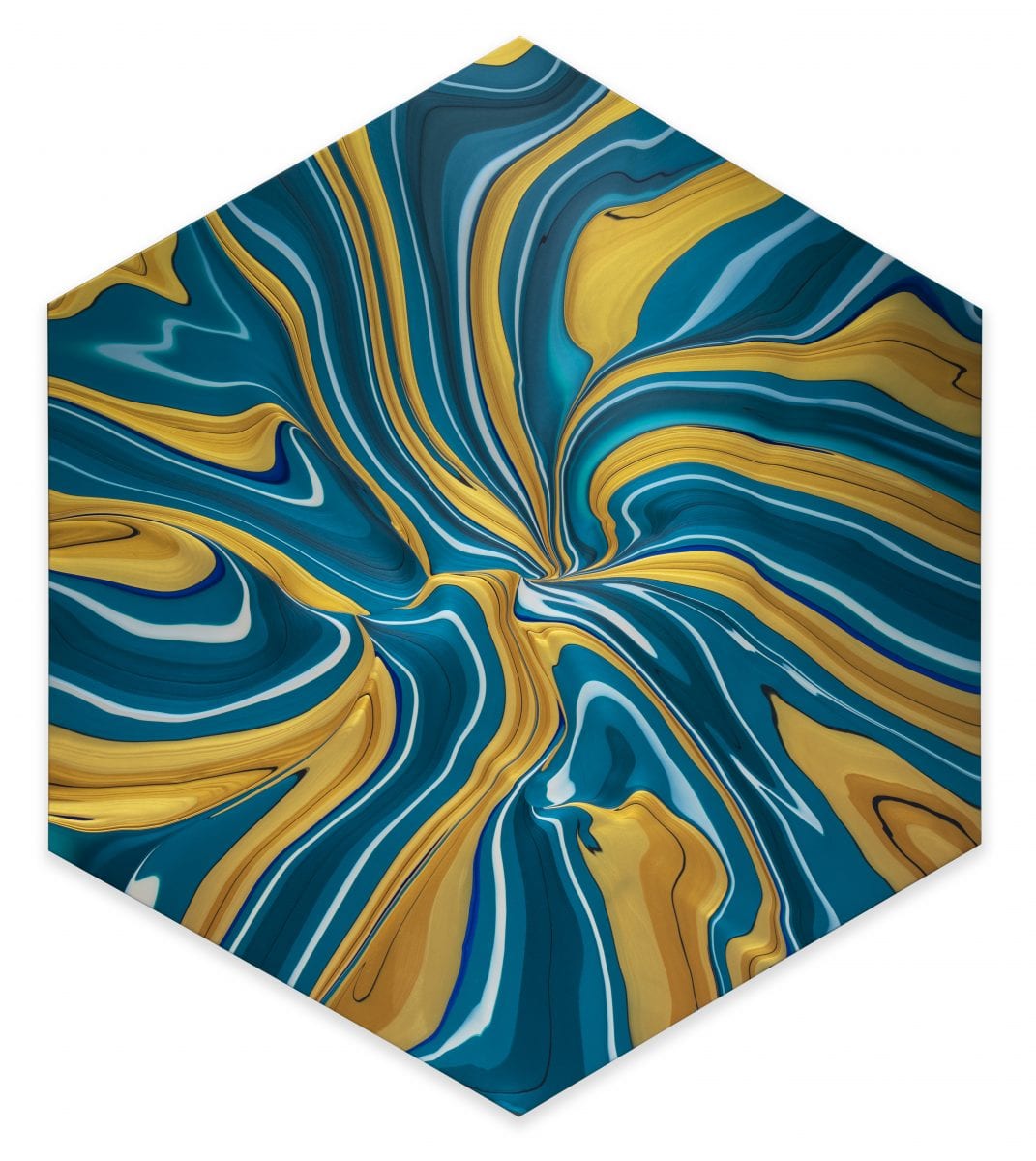

acrylic on canvas over hexagonal-shaped wood panel

78 x 67 in.

Photo by Alan Shaffer, courtesy William Turner Gallery

Artwork courtesy of Andy Moses

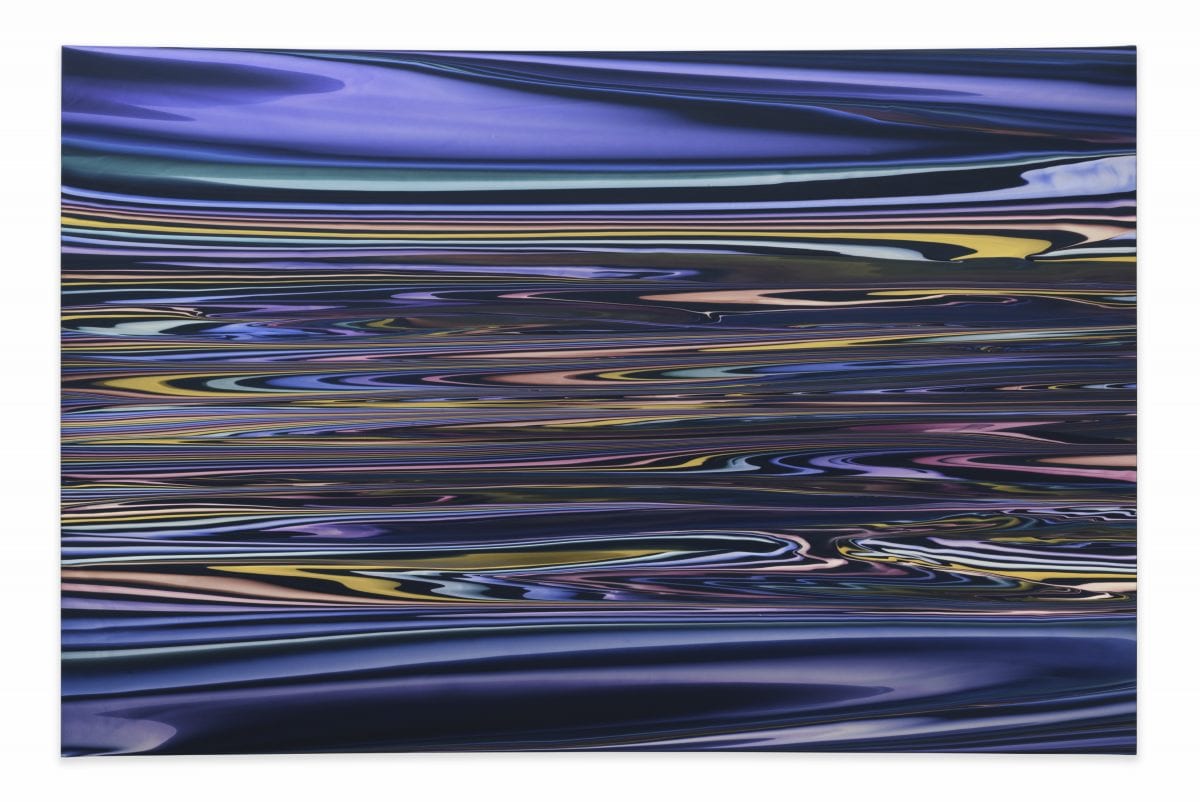

When looking at a concave panel such as Geomorphology 1707 and approaching it straight on the suggestion of the curve feels subtle. After moving around the painting and viewing it from either side the true evidence of the curved surface is realized, reminiscent of a movie screen. In what ways has cinema informed the concave panel?

I went to CalArts to study film and while I was there it just seemed like there were a lot more interesting people in the art department. I was very interested in film. Seeing 2001: A Space Odyssey in 1968, [I was] six years old when it first came out I remember what a huge impact that had on me. The idea of the screen going all the way around and looking at infinite space and being surrounded by an image.

Your tenure at CalArts signifies an unexpected transition from the film to the art department. It was also a time of personal growth as you began to create your own artistic identity.

My father was an Abstract painter who pretty much told me and my brother, “you can do anything you want, you just can’t be a painter.” It’s something we never really delved into when we were kids. Within about two or three months of being at CalArts, I was starting to realize I was way more interested in performance and sort of these other things. So I did a performance called “Father’s Knows Best,” where I made recreations of my father’s paintings, and then at the opening, I took them off the wall and destroyed them on the ground. When making those paintings it took me about five minutes [to realize] that “this is what I wanted to do.” So from that point on I stopped making films, shifted fully into the art department, and I just wanted to learn about paint and what it could do. So immediately I started working on the floor and I started pouring different kinds of paint, trying out different things, and seeing where that lead me. And I enjoyed it so much I realized it was going to take me my whole life to kind of figure out where I’m going.

acrylic on canvas over concave wood panel

60 x 84 x 4.5 in.

Photo by Alan Shaffer, courtesy William Turner Gallery

Artwork courtesy of Andy Moses

(Left to Right)

Photo by Alan Shaffer, courtesy William Turner Gallery

Artwork courtesy of Andy Moses

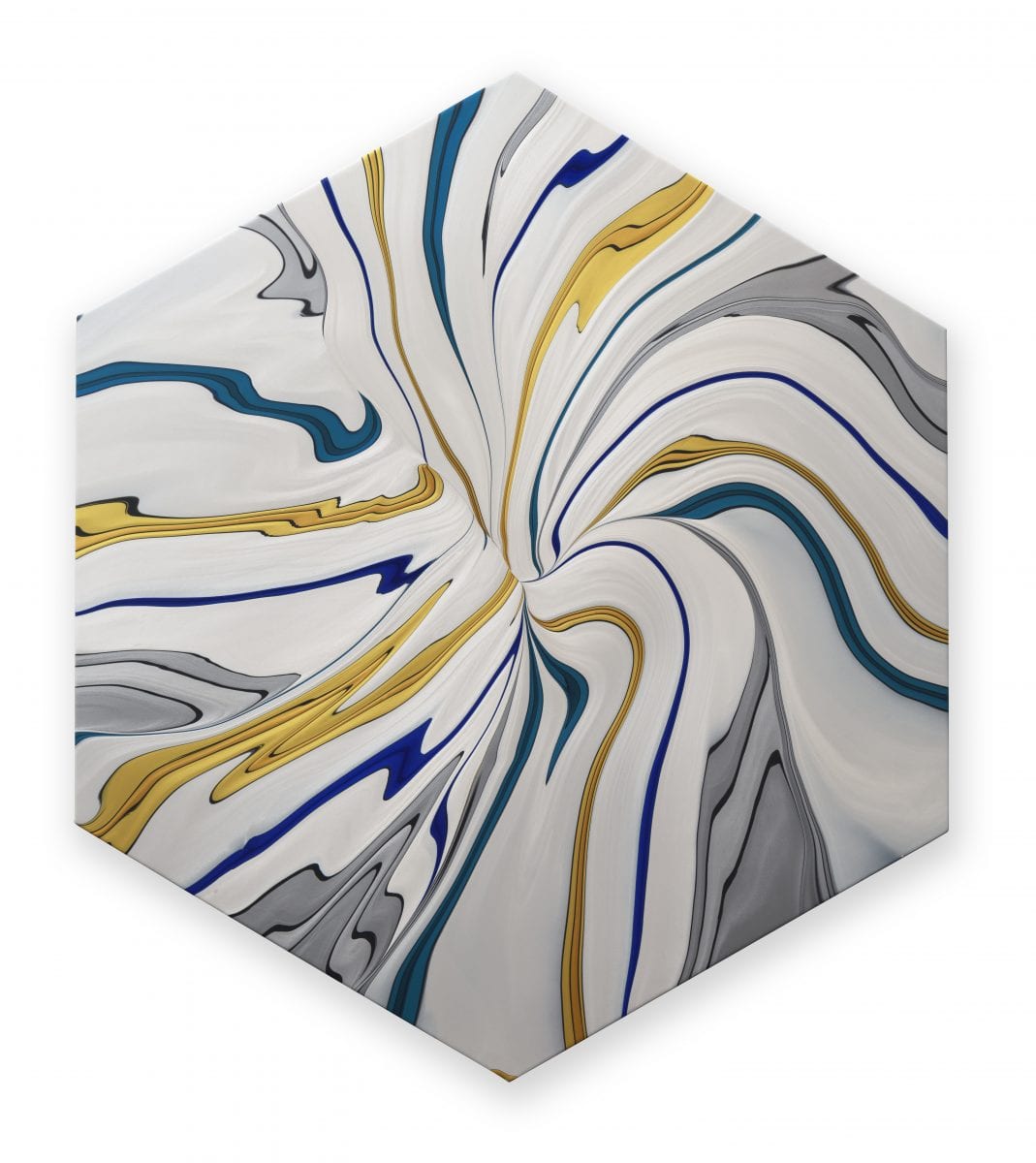

acrylic on canvas over hexagonal-shaped wood panel

60 x 52 in.

Photo by Alan Shaffer, courtesy William Turner Gallery

Artwork courtesy Andy Moses

Did you find distancing yourself from the familiar landscape of Los Angeles help to identify a new perspective about the world that you wanted to create in your paintings?

I moved to New York in ‘82 I lived there for the next 18 years and I pretty much explored that process and that way of applying paint. That took me in a lot of different variations on these paintings but when I moved back to California in 2000, I had a studio in Malibu. It was a tiny little house, a shack, but it was on the water near MoonShadows.

Your story starts in California where you were born and raised in Santa Monica. In the early 80s, you depart for New York after two decades of discovering and refining your style; you return to the beaches of California in 2000. What response did that return West prompt within you?

Stepping out onto the deck there was water flowing under it and looking at the horizon like I did in my youth, everything came through, and thought “I’ve got to find a way to connect with this new environment.” And I started pouring just this one kind of pearlescent white paint across these surfaces to see what it would do and it immediately started suggesting horizon, infinite space, and I thought alright, “the next thing I’ve got to do is figure out a shape where it’s going to relate,” and it was just obvious that it was a concave curve. And I did those paintings probably for about a year and then I thought, “alright I’ve got to move to the next thing,” so I think I went gold next then blue next and they were all monochromatic and then probably within a year and a half or two it felt time to start investigating something more complex. So I just slowly built up the color in that same kind of paintings probably for the next six years up until 2008 and then it just felt I was ready- I wanted to make something that added to it but also connected to some earlier work. So I started trying to figure out ways to get these shifting lines. It took a lot of experimentation to figure out ways of preparing these buckets that I could still pour that would have all of these variations and it took a couple of years probably to get a sense of what I was doing and where it could go with this.

acrylic on canvas over concave wood panel

54 x 84 x 4.5 in.

Photo by Alan Shaffer, courtesy William Turner Gallery

Artwork courtesy of Andy Moses

(Left to Right)

Photo by Alan Shaffer, courtesy William Turner Gallery

Artwork courtesy of Andy Moses

Recent Works at William Turner Gallery is your first solo exhibition in Los Angeles since the 2017 exhibition Andy Moses: A 30 Year Survey at the Pete and Susan Barrett Gallery, Santa Monica College. In what ways do the two exhibitions engage in a dialogue with each other?

It’s a great bridge. That show brought me to this. It was the first time I had ever shown the hexagons which I started about two years after the circles and then I hadn’t done concaves probably in about three years so I did these. I feel like this is a culmination of everything I have done all coming together and it’s interesting to see. Seeing the survey, seeing all the different bodies of work, how well they related to each other in the show started to make me think of going in a lot of different directions and hang them all together and tell different stories.

Photo by Alan Shaffer, courtesy William Turner Gallery

Artwork courtesy of Andy Moses

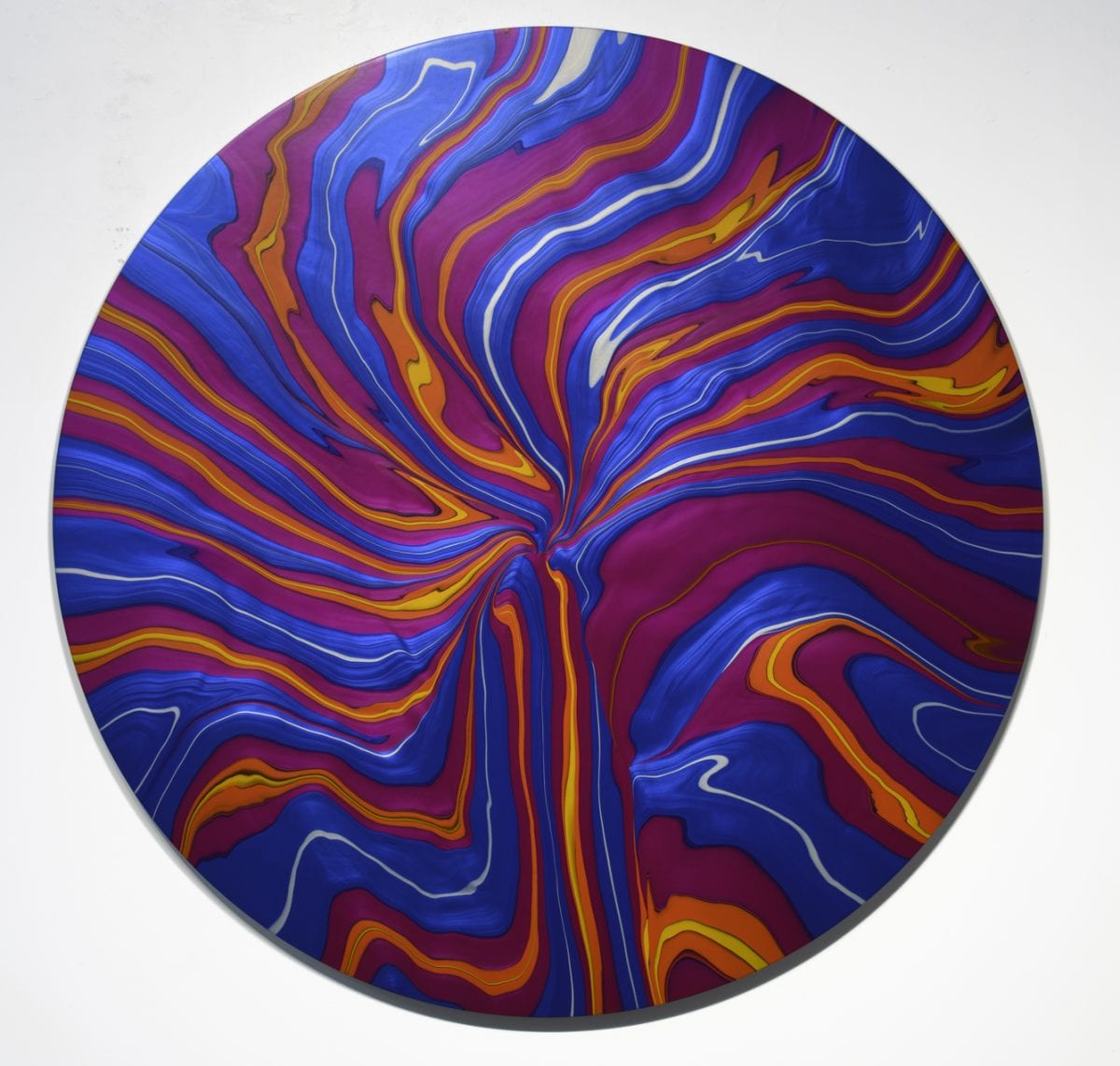

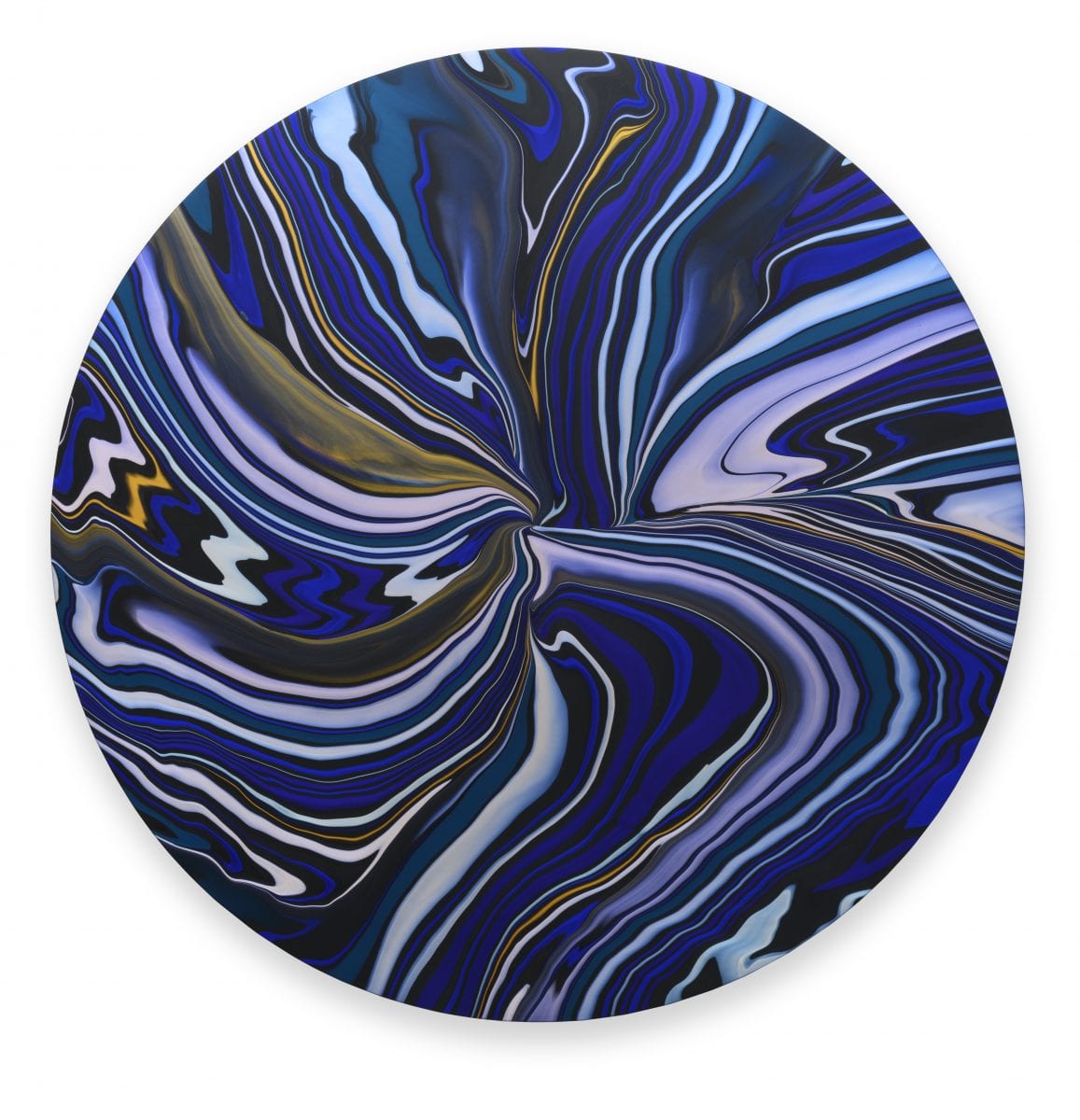

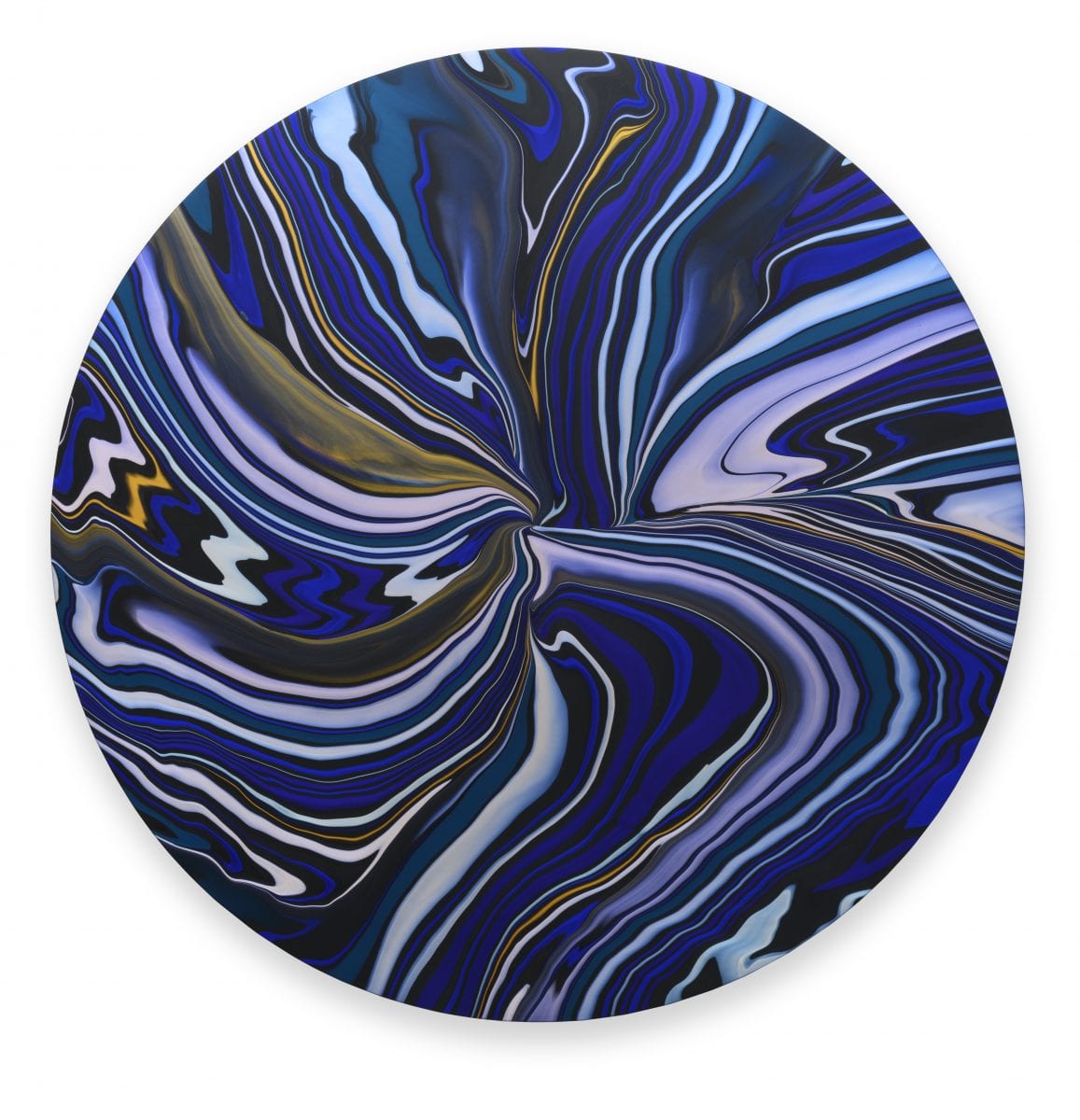

acrylic on canvas

over circular wood panel 72 inches diameter

Photo by Alan Shaffer, courtesy William Turner Gallery

Artwork courtesy of Andy Moses

The hexagon seems an intriguing move as it’s a form between a circle and a concave surface. There is a surface tension where the hexagon is trying to compete and pull the paint in each section of the canvas and I think that fluidity is so magical.

Hexagons are hard to do because if things don’t end up pretty much converging right in the middle, as soon as they’re a little bit off one way or the other it just isn’t very strong. It feels like it has to have that geometry yet it still works so well with this very fluid motion. When you think about hexagonal things that exist, it’s probably a big move toward geometric shapes in the 60s and 70s and there’s a lot of American art with those shapes, but the shapes, the painted area always reinforces the shape. It’s this idea that I would use the shape as a continuum and the painting would become whatever it is itself that there would be this tug of war between this very fluid application of paint and this very geometric shape.

The paintings feel like galactic artifacts.

I want these to take you on some kind of journey in your mind and have them both reinforce but also question, “Where are we? How do we fit into the grand scheme of things?” I like this idea of creating something that has a real sense of motion because to me that’s something that light is filled with. It’s a big challenge to take something static like a painting and give it a sense of fluidity, a sense of motion, a sense of change so, to me, you’re looking at the painting, it’s like that now but it feels like in five seconds it could be something else and then something else again. So very much that notion of introducing movement and change into a painting and the challenge is to be able to suggest that which isn’t easy.

acrylic on canvas over hexagonal-shaped wood panel

55 x 48 in.

Photo by Alan Shaffer, courtesy William Turner Gallery

Artwork courtesy of Andy Moses

acrylic on canvas over hexagonal-shaped wood panel

36 x 32 in.

Photo by Alan Shaffer, courtesy William Turner Gallery

Artwork courtesy Andy Moses

Is that where the infusion of the pearlescent colors come into play?

Yes, these two paintings here have this metallic gold in them and I played around with this color before but never on that scale. Never have the pours being that wide and never on that scale and it’s pretty amazing what they do. If you go up to them you can see all these lines that move and shift and change. So the gold is pure metallic, this color was a pearlescent blue but even these colors here are a combination of a standard green with pearlescent colors mixed in so that’s how I get not only the shimmer but also all those tiny lines between this band of color is because it picks up the paint slightly different.

The color theory creates a dynamic relationship between the surface and the viewer. The engagement creates a perspectival shift that accelerates the present moment.

Good, I’m glad you’re getting that. I feel like there is. That’s what I aim to put in, create this almost electromagnetic field. As you walk around them hopefully the angle suggests something slightly different. I want a painting that’s interactive that you want to come close to and each different vantage point depending on how far away you are there are different orbs in looking at it so it’s something that has to interface with to get the whole totality out of it. I want to make work that’s life-affirming and hopeful even though that’s not always the popular thing to do. For me, it’s everything. I want to make something that gives you hope.

(Left to Right)

Photo by Alan Shaffer, courtesy William Turner Gallery

Artwork courtesy of Andy Moses

(Left to Right)

Photo by Alan Shaffer, courtesy William Turner Gallery

Artwork courtesy of Andy Moses

Photo by Alan Shaffer, courtesy William Turner Gallery

Artwork courtesy of Andy Moses

During this incredibly insular period, the creative process feels as though it’s suspended. What has surprised you most about the past year?

I feel lucky that this time has come up- I’m 58 years old so I’ve lived enough different chapters of my life where this is a sort of interesting chapter for me. I could imagine if I was a lot younger it would be probably more disturbing- the moment we’re in. But somehow it’s given me this energy and a focus. I feel like I probably made the best paintings I’ve ever made because of this situation.

The exhibition points to the specific handling of paint but the surface is brushless. What is your interaction with the canvas?

I have a white canvas [on a standard table,] and I have all these containers of paint. I sort of know where I’m going but I try to let my mind be free so when the paint starts to flow I’m reacting exactly at what I’m seeing in front of me rather than what I thought about before. I have to respond to what’s happening at the time to make it turn out and it’s exciting. Each one is a new adventure and the more I do, the more I have an idea of where I think I’m going to go but it’s full of surprises too, which makes it exciting.

The process of pouring demands that you remain present. While you can demonstrate control over some elements there remains a moment of surprise.

There’s a lot that happens that’s outside of my control and then I have to respond to that so it’s a real collaborative process. Collaborating with the forces of nature so to speak. [The painting] is on a standard table but can walk completely around it. For the circles and the hexagons, I am pouring paint from every direction, but with the [concave panels] I’m usually pouring it up and down one side and then running it across. It’s a very different process between the horizons and the circles and the hexagons.

acrylic on canvas over hexagonal-shaped wood panel

36 x 32 in.

Photo by Alan Shaffer, courtesy William Turner Gallery

Artwork courtesy of Andy Moses

acrylic on canvas over wood panel

60 x 84 in.

Photo by Alan Shaffer, courtesy William Turner Gallery

Artwork courtesy of Andy Moses

acrylic on canvas over circular wood panel

72 inches diameter

Photo by Alan Shaffer, courtesy William Turner Gallery

Artwork courtesy of Andy Moses

The geometry of the surface, therefore, dictates your movements and the application of paint.

It does! It definitely does. It’s a very physical process. The paint is very thick here. It’s probably the thickness somewhere between milk and a milkshake I like to say. Probably a little closer to a milkshake. If it gets too thick later on when it dries you will get this sort of lumpy kind of feeling but if it’s too thin it doesn’t feed this kind of physicality so finding the right viscosity. For each color, I have to mix a slightly different viscosity from each other to get them to separate in the best possible way. As long as I know my moves and don’t overwork them. Every color and everything stays totally clean in terms of the lines. After a while, it will start to turn to mush. So decisions do have to be made and after a certain point, I have to know when to stop.

It seems that you can only exercise so much control despite understanding all of the factors at play.

It’s left to chance. But once it starts to get established I can do a fair amount still to manipulate what’s happening at the center but everything I’ve poured around the side and each flow start to come in. There are probably about a dozen different flows there and the point where everything reaches is about three-quarters of the way through the process. Once that reaches then I know I’ve got paint on the whole surface, but now I can manipulate it by lifting any different side of it just a little bit or a lot to kind of create energy to go in a different way.

You’ve been experimenting and refining the viscosity of the paint depending on the scale to discover the perfect cocktail if you will.

Right. There’s a lot of technical stuff going in that I’ve had to figure out, but the great thing is once the paint starts to flow, I get to forget about all that and just see this dynamic image create and re-create in so many different ways and at a certain point I have to “that’s it, it’s finished now.”

The inclusion of the hexagon studies grants insight into the process of mixing the colors and reveals how the scale influences which colors best complement the surface.

The great thing is I get to refine it and I get to explore new things. It’s all kind of part of the activity, so I guess at some point along the journey I’m more interested in refining it, and at other points, each color next to each other color behaves differently in terms of how they show up essentially. The reds and the greens will expand on the canvas, the blues always contract and every other color is somewhere in between. So for each color palette, I’ve done several studies before I go large before I can figure out how to do it and make it work on a large scale.

You mentioned that the paint pours and interaction feels as though you are “collaborating with forces of nature.” Are you still energized by the process?

Absolutely. When I do one of these paintings each one I do is one of the most exciting moments of my life up to that point. That’s what keeps me going with these and having these supernatural feelings. I have to go surfing to get that. Doing one of these is as good as surfing and I end up with something afterward that I can have forever. It does for me in my mind re-creates that sensation only it’s better. Doing one on this scale is like one of the best waves I’ve ever surfed in my life. I’m very fortunate to have found this approach. Each one is so much fun to do. There is a lot of exploration and in the end, I have to let it do what it’s going to do. So I’m just kind of steering the process and I like the fact that it’s creating its own energy and identity and I’m collaborating with it.

(Left to Right)

Photo by Alan Shaffer, courtesy William Turner Gallery

Artwork courtesy of Andy Moses

acrylic on lucite panel

20 x 17 in.

Photo by Alan Shaffer, courtesy William Turner Gallery

Artwork courtesy of Andy Moses

Andy Moses: Recent Works is on view at William Turner Gallery through February 10, 2021, by appointment. Schedule your viewing for the exhibition.

Photos by Alan Shaffer, courtesy William Turner Gallery. Artwork courtesy of Andy Moses.

Featured Image Credit:

Andy Moses, “Geodynamics 704,” 2020 (Detail View)

acrylic on canvas over hexagonal-shaped wood panel

36 x 32 in.

Photo by Alan Shaffer, courtesy William Turner Gallery

Artwork courtesy of Andy Moses

Installation Magazine © 2021