The breadth and depth of the artist roster at Jack Rutberg Fine Arts challenges the collections of many museums. Installation and Jack Rutberg have a lot in common – we’re both based in Los Angeles and we are both committed to an international focus of artists working across all disciplines. We asked the gallerist and dealer to select works by just a few of the artists that he champions in the gallery’s permanent collection.

Installation Magazine: The styles of Jordi Alcaraz, Hans Burkhardt, Patrick Graham, Bruce Richards, Ruth Weisberg, Jerome Witkin, and Fransisco Zúñiga present a wide aesthetic range and approach. How do their works represent the philosophy that drives your gallery practice?

Jack Rutberg: They pique my interest. They go from the head to the gut but they never bypass the heart; and I think that is the single thing that unites them. It’s the nuance that they offer that gives them a unique voice. Whether they’d be abstract, more conceptually driven, or figurative, it’s this aspect of unique vision, having a very humanistic sort of connection. The most powerful works for me- it doesn’t matter how visceral, how big or how painterly they are- they really speak in private whispers.

How did you enter the art scene as a gallerist and dealer?

Art captured me by virtue of this remarkable thing called “history” and where I stand in relationship to that history. I’m not trying to make history, I’m just humbled by it. My background is in original prints – from Old Master prints to Early Modern prints. The word for print is kind of sometimes pejorative of reproductions or they’re computer generated facsimiles, but I’m talking about of the hand and the human touch that is involved in that progression. Learning about original prints was beneficial to me in two ways; one, it allowed me to learn about things to where my knowledge, whatever knowledge I gained, I could use again and again. That is the beauty of multiple originals as opposed to a single drawing or painting, you never see it again, if you are even lucky enough to engage it. But with a print, you have context, you have the ability to connect dots by comparative analysis, you develop a sense of connoisseurship as well because there is a comparative issue going on from one impression to another.

Where do you look for new artists?

It’s very seldom that I’m looking for new art but it finds me. You stumble on it in the same way that you can’t negotiate relationships, if you are lucky enough to fall in love its not by virtue of negotiation or calculation, its an incidental thing in context to a daily experience and I think that’s the way I view art, in terms of those artists that have somehow entered into my focus.

DEEP CAPTIONS

JORDI ALCARAZ

He’s a remarkable artist. I remember being at an art fair in Chicago some years ago, being utterly exhausted and my eyes were bleeding from having to engage so much stuff. I was ready to leave when all of a sudden, I walked into a booth of an artist who I had never seen before and had a visceral experience. Suddenly I could breathe. I felt as if I had just stepped into this amazing Zen garden and had this undefinable experience. I couldn’t sleep all night after seeing this work. I was thinking I was seduced by a trick, because I never trust that first impression. It’s usually a trick that one is impressed with — some facile sort of novelty and the further I got away from it, the less I trusted what I had experienced. You can take a visual image with you, but an experience lasts while you are there. You can try to reconstruct it but it’s virtually impossible. I read the catalogues that I took about this artist’s work. I couldn’t understand what I was experiencing: it was something very new to me. I got up in the morning, went to the fair wanting to revisit this, and when I stood in front of the work, I knew that this was the real experience: this was the real McCoy. I didn’t know what to do with it, so I was fortunate enough to be able to commit to buying every work they had. I brought them back to Los Angeles and I knew I wanted to share them. I didn’t want to sell them because I knew I wanted to use these works to introduce people to this artist, and I wanted to be the one to do it. I seduced his gallerist in Madrid to communicate to the artist that I wanted to introduce his work in America and sure enough we prepared an exhibition. It was the single most successful exhibition I’ve ever had, where collectors would come in and say something to the equivalent of: “I don’t typically look at work like this, I don’t know what it is, but I really want it.”

oil, assemblage with skulls on canvas, 60” x 72” x 8”, 1967-68.

HANS BURKHARDT

The most powerful works, for me, it doesn’t matter how visceral, how big, how painterly they are, they really speak in private whispers. And the artist that taught me that more than any other would be Hans Burkhardt. When I met Hans Burkhardt’s work, I met him before I met the work … I wasn’t prepared to be moved in the direction that I was taken. What I saw was a remarkable body of work that is so deeply rooted in the history that I knew a little bit about, of course who doesn’t know about American Abstract Expressionist and then here is a body of work that resided here in Los Angeles, that I was completely ignorant about … and I was utterly staggered by how protean an artist he was, you know, if an artist can be judged by his expansiveness of vision then Burkhardt has to be among the greatest artists of the 20th Century. There was obviously the early beginnings, the influences, and then the transcending of those influences but what is so amazing to me is here is an artist that it doesn’t matter whether you are looking at a work from 1994 or you are looking at a work of 1934, they are equally compelling and there was never this kind of redundancy … and Burkhardt was always moving forward finding something new in the body of work but the linkage between the early and the late work is remarkable. One of the things that I would say is that I’ve never felt a compelling interest in regionalism, regionalism is interesting for its own sake; but when I view the works of Hans Burkhardt I put him in context to artists internationally, but what makes him remarkable is that he transcends his regional boundaries and limitations.

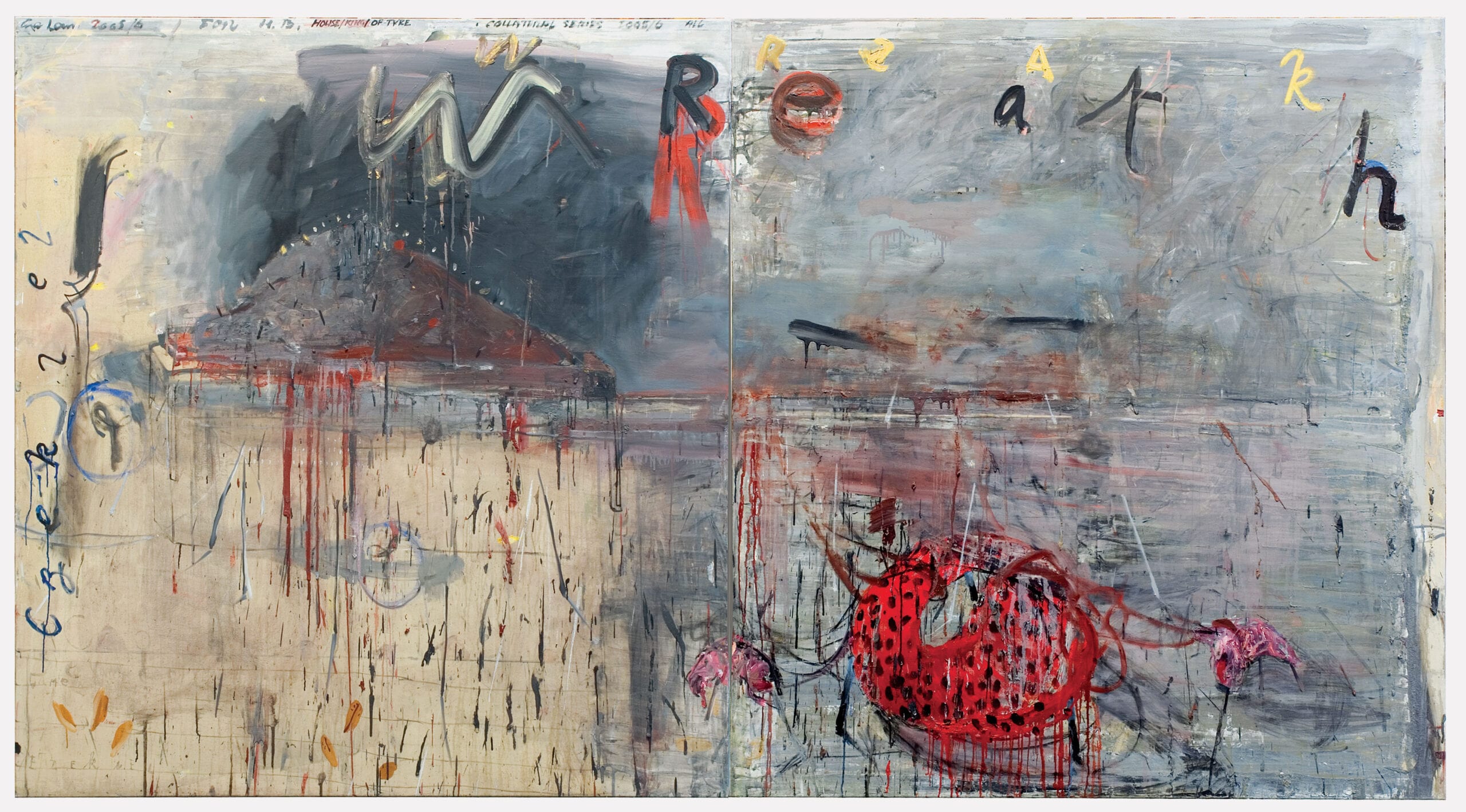

PATRICK GRAHAM

He’s a difficult artist for some. The work is different depending on which period, they can be dark, they can be raw. There’s a sense of poetry, this sense of vulnerability that impacts upon us. Vulnerability is something that may be a quality that humanizes us when we engage a work of art. So when you come in front of a Patrick Graham, you don’t quite get it, you don’t discover it quickly, but you sense a vulnerability not only of the artist but in ourselves. And what I’ve learned about what makes a powerful statement for the viewer is when we are humbled by the experience. We don’t necessarily benefit from the knowing; it’s from the receiving. And when you come to a work of art with your intellect and all of your knowledge, then you come to it as a pathologist comes to a human being. If you really want to learn about a work of art in the same way that you learn about a person, you have to not take the pathologist’s view of tissue samples and microscopic analysis, it’s about allowing the work to make its impact. Artists like Patrick Graham have devastated other artists in this gallery, they’ve devastated viewers who are unprepared for their own humanity when engaging it, and to witness people literally crying in front of a Patrick Graham painting without even understanding why — it’s just that they’ve been touched and we are so seldom touched.

BRUCE RICHARDS

Bruce Richards does these very refined and surreal works that melds the messaging of an Ed Ruscha, except there is a kind of beautiful surface that harkens even back to the Surrealists. They are not overworked, they are very very fetishised in a sense, but what intrigued me about Bruce was the remarkable intellectual approach to create images that are distilled and they are layered with tremendous amount of explanatory, oratory. I’ve been the beneficiary of this experience by having these fantastic conversations with Bruce, and I think they are wonderful. And here is an LA painter who was very much part of the LA scene in the 70s in particular and had a lot of exhibitions, was featured somewhat recently when Pacific Standard Time covered Orange County, they did the recalling of the artists who came out of Irvine. I think that Bruce brings something very unique to the table and my curiosity and intellectual interests were piqued by his work.

45” x 46”, 1990.

RUTH WEISBERG

Ruth Weisberg is a narrative painter and one that deals with notions of memory — both artistic memory, personal history, feminist history, and Jewish history. All these notions of identity are layered through the lens of memory. A very influential artist here in Los Angeles and teacher here for many years. She was the Dean of the School of Fine Arts USC; so Ruth and Hans’s styles might be completely opposite but the mutual regard for each other was profound. I think LA is a great place to be from, and a great place to work, but it is never been a great place to be celebrated and if you were it was always for a very very short span of time. LA is all about celebrity and the moment and about the new, not about the substantial.

JEROME WITKIN

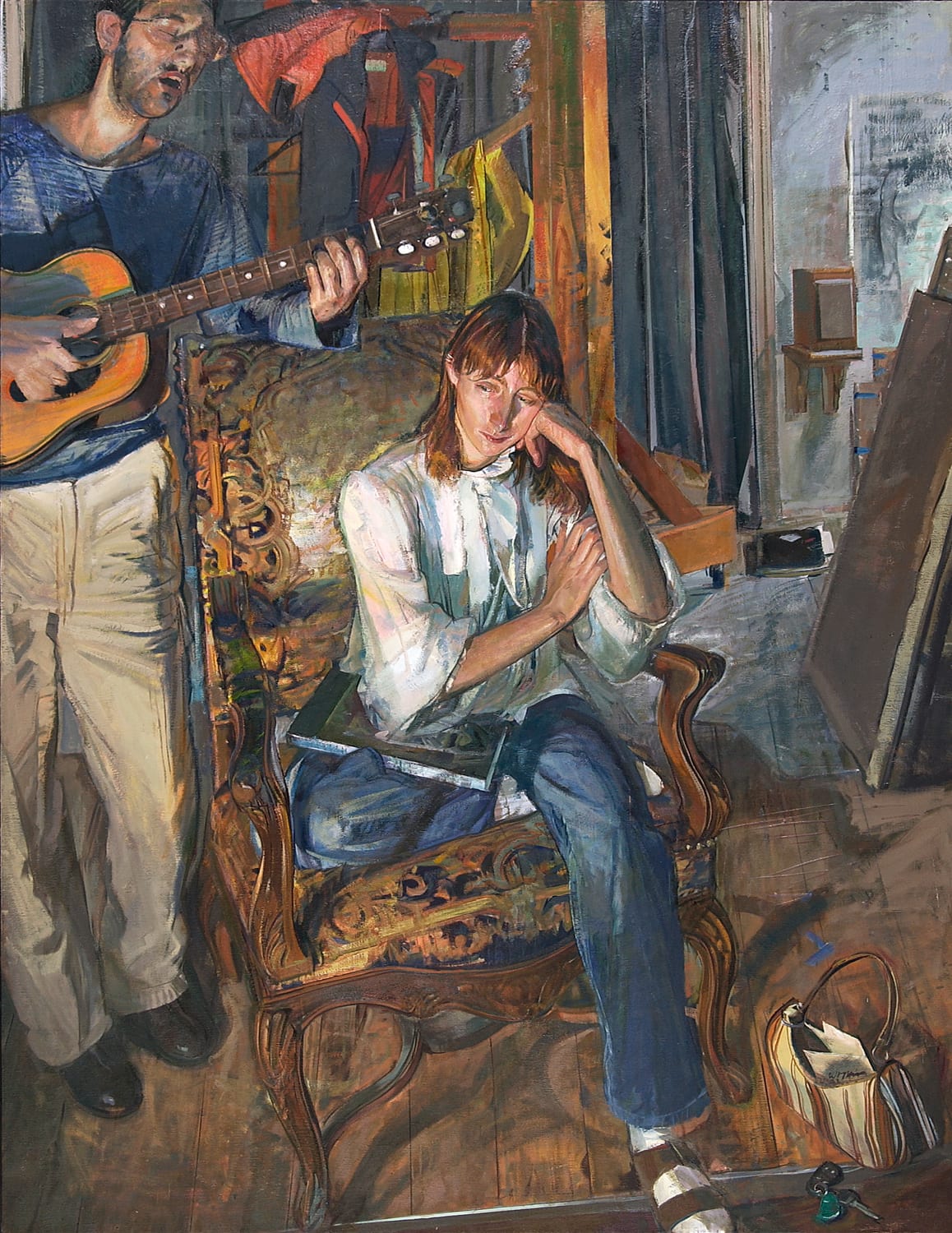

Jerome Witkin is exactly the kind of artist that will knock you on your rear — because I don’t think there’s an artist of greater facility and vision than Jerome Witkin. He’s been cited by curators and critics who know the work as being unequalled in the world. Now that’s a remarkable sword to fall on and live by but Jerome Witkin has tackled subjects that are unimaginable. He is able to depict the un-depict-able. This is a highly figurative artist that when you are at any distance from any painting, even the photorealist passages in his large paintings, you discover the bravura of brushwork, the gesture is so unimaginable because how — I’m not a painter so I’m awed and humbled by the virtuosity of someone who can evoke the most complex subject with merely a brushstroke. It is distilled to its essence and it is absolutely defined with a precision that is unthinkable and yet just charged with psychological ramifications.

A portrait by Jerome Witkin peels back the layers of a person’s psyche in ways, in ways that are really really hard to imagine. He’s tackled some of the biggest subjects in history, such as the Holocaust, which has been tackled by numbers of artists but the only time it has been dealt with effectively is in the abstract. Because how do you possibly depict the indescribable? Jerome Witkin has done that in highly detailed literal ways through psychologically charged subjects and a narrative that goes to the kind of narrative that can only be seen in the old master paintings: the nuance and symbolism is not so abstracted as a lot of the old masters, who used certain colors, and certain mannerisms to imply something else — Jerome Witkin puts it in front of you and it is hard to take. But its very, very easy to make a painting that is grotesque and powerful — it’s a whole other thing to imbue it with humanity. And Jerome Witkin is able to create humanity that is stupefying. I mean we were stupefied by the response. When I showed the Holocaust paintings, I remember having Holocaust victims coming and I remember very specifically how one woman stood in front of a painting, and I thought she was going to sock me in the jaw because her fists were clenched but she stood there and said ‘no one has ever understood until now.’ That was an amazing experience. I had letters from people — a woman that actually said to me that until this day, of seeing the exhibition which I did not think I could even take in, I’ve carried a boulder on my shoulders, I was never a whole person, and seeing that exhibition, I feel for the first time that I have been made whole. That is dramatic and melodramatic and God’s truth by the way, I’m not exaggerating at all, I mean that very literally. But these kinds of experiences have ruined me as a dealer because its made the bar so high that its really hard to not somehow compare that experience to others.

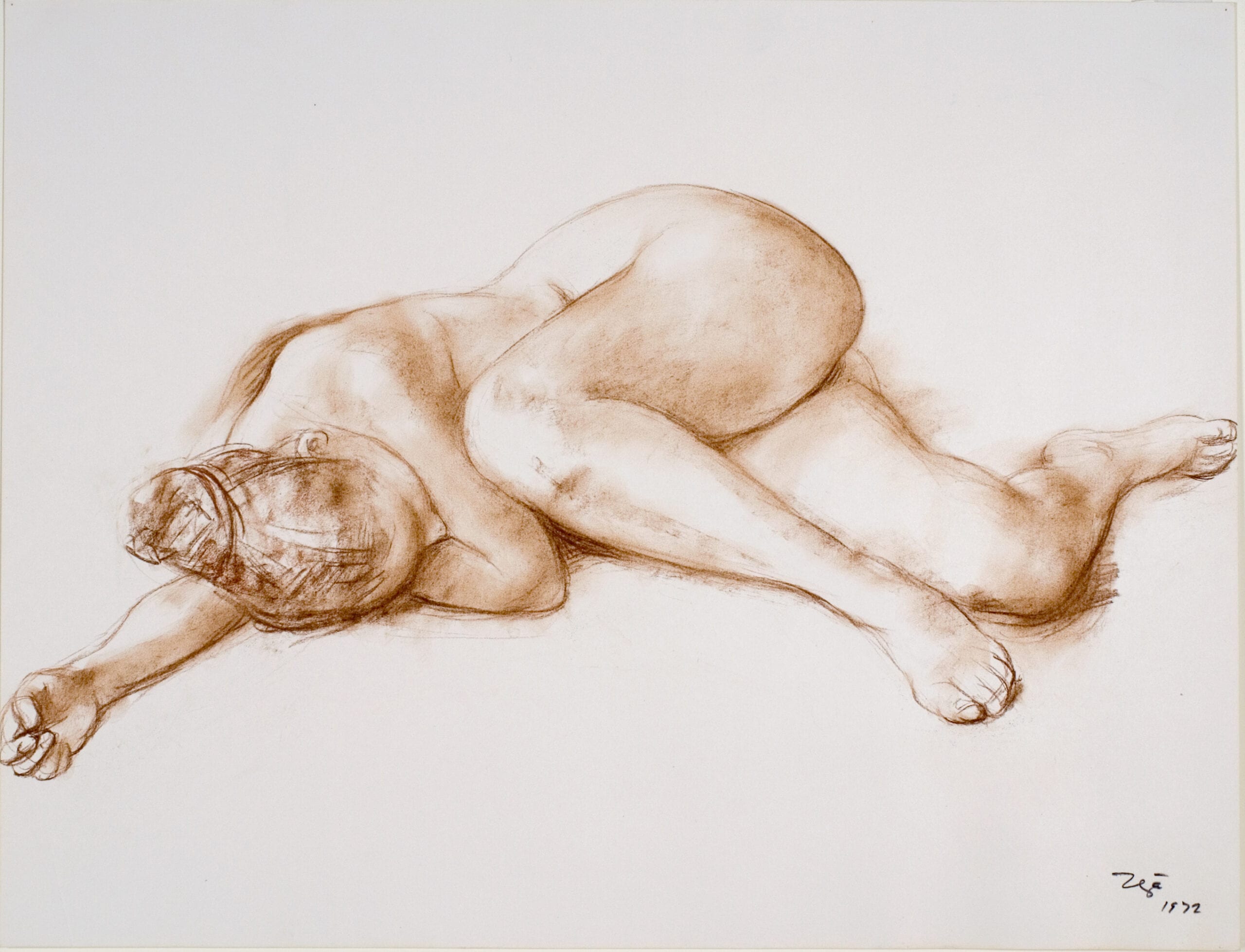

drawing on paper, 19 ½” x 25 ¾”, 1972.

FRANCISCO ZÚÑIGA

There is a remarkable quality about Francisco Zúñiga who was Costa Rican by birth and lived most of his life in Mexico. Both nations claim him a national treasure, in a sense, but has made a remarkable universal sort of impact. People come back to the work and they automatically think that is something of an indigenous culture from where they come from. He is an artist that has brought the human figure, very specifically the female figure and then viewed it with a kind of dignity and power. Celebrating the maternal and the female as a heroic form, I think is a remarkable quality to reduce something to its elemental form. I think Zúñiga is primed for a rediscovery in a sense by a generation that is being seduced by things that have less to do with the humanistic and more to do with the reactionary.

CLOSING THOUGHTS

The holy trinity for me in some respects was Witkin, Burkhardt, and Graham who were somehow able to transcend all of those kinds of categorizations that you know, that are put out there in boxes for people to understand. There’s so many aspects to these artists — all of whom have had a remarkable impact on me, certainly. I have the benefit of getting these wonderful love letters from people who have been here — its very fulfilling in that regard. Running a gallery is a very painful process — you care a great deal about it, you blend the contrasts of commerce, history and aesthetics in a time where we’re wrestling with even the definition of things as simple as art.

I’m a champion of these artists. It’s the hunt. It’s the thrill of the hunt. The thrill of presenting an exhibition is something else entirely. It’s presenting a play — its this remarkable joy of sharing. And its very selfish. It’s very self-oriented. I get nothing but gratification out of these things. You balance that and hope that you can actually sustain it and make a living out of it.