Four years have passed since visiting Enrique Martínez Celaya at his Los Angeles studio. Returning to the immaculate compound assuages my mind, knowing that despite the cataclysmic changes that have dictated the recent circumstances of my world, the studio remains free of the impurities of an otherwise unpredictable landscape overrun by chaos and disorder. Natural light floods in from the multitude of skylights nestled within angular and soaring ceilings. Large scale paintings are placed within each room, which in truth feels more like a series of galleries and thus what I wished all gallery spaces were actually like. The grandeur is understated by the purity of crisp white walls, concrete floorings, and the absence of unnecessary furnishings. Within these walls, we are not merely entering a studio but have been permitted to visit the inner workings of Enrique Martínez Celaya. There is deeply palpable energy- the presence of ideas, drawings, writings, and paintings are whispering and calling for my attention. While their message is not entirely clear the urgency is understood and I remain alert.

The faint chirping of birds in a wired cage with an A-line roof now resides in a newly renovated area of the studio, which serves as a reminder that while much of the space has remained the same, it too has changed. The aviary leads the eye up to an attic of archived works that are meticulously wrapped and labeled with a precise infrastructure denoting the year, name, and other details of note. Along the French doors are books of poetry still sealed in plastic, published by Whale & Star Press. Only a handful of paintings are installed in the two front galleries. The paintings on view have been given space to breathe and reveal themselves to the artist after he has considered them complete. The paintings soak in the natural light while patiently waiting to be transported and presented in a forthcoming exhibition.

Turning the corner into a third gallery, the artist stands next to a red metal-tiered cart placed near the painting currently undergoing revision. The glass palette has oil paint of muted brown, orange, and red and hints of gold. The cart, the paint cans on the corners of the bottom slat, and the brushes are pristine despite the traces of dried paint from days and years past. The vestiges speak to works that no longer occupy the studio and await those yet to be born. Wearing a uniform of a black button-down collared shirt with the sleeves rolled to the elbows, dark blue trousers, and black laced boots, Martínez Celaya looks to the golden apple tree and considers one specific area of the trunk and branch. While there is wet paint on the palette, the canvas, and the brush, there is no wasted drop. There is no evidence of paint on his clothing even though there are stains ingrained in the fibers. No splatter. No drops. No effort is unaccounted for. Every action is deliberate.

For the next hour, we stand before what is now titled, “The Promise of the Most Whole.” Without hesitation or complication, Martínez Celaya conducts an entire conversation whilst mixing paints and working. I can’t help but wonder if the painting will remain in this state when it is revealed at the artist’s forthcoming solo exhibition at Kohn Gallery, “The Tears of Things,” his first solo exhibition in Los Angeles in four years.

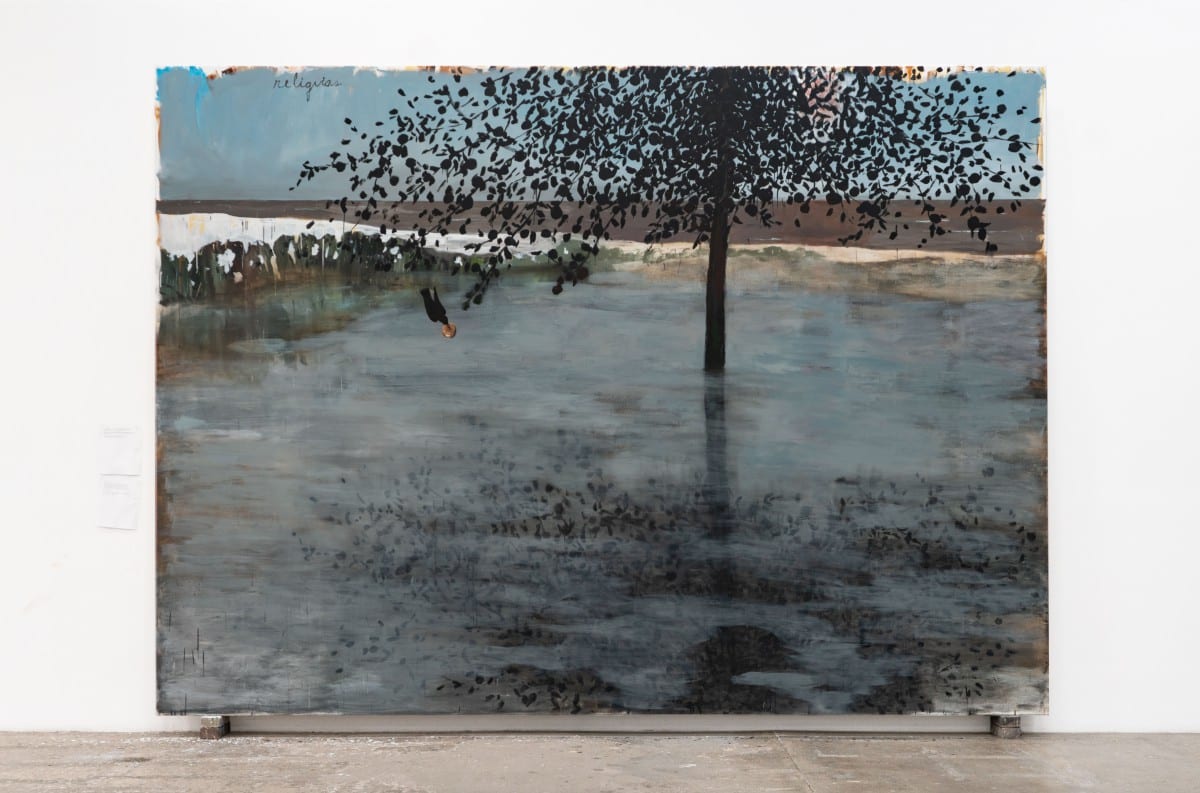

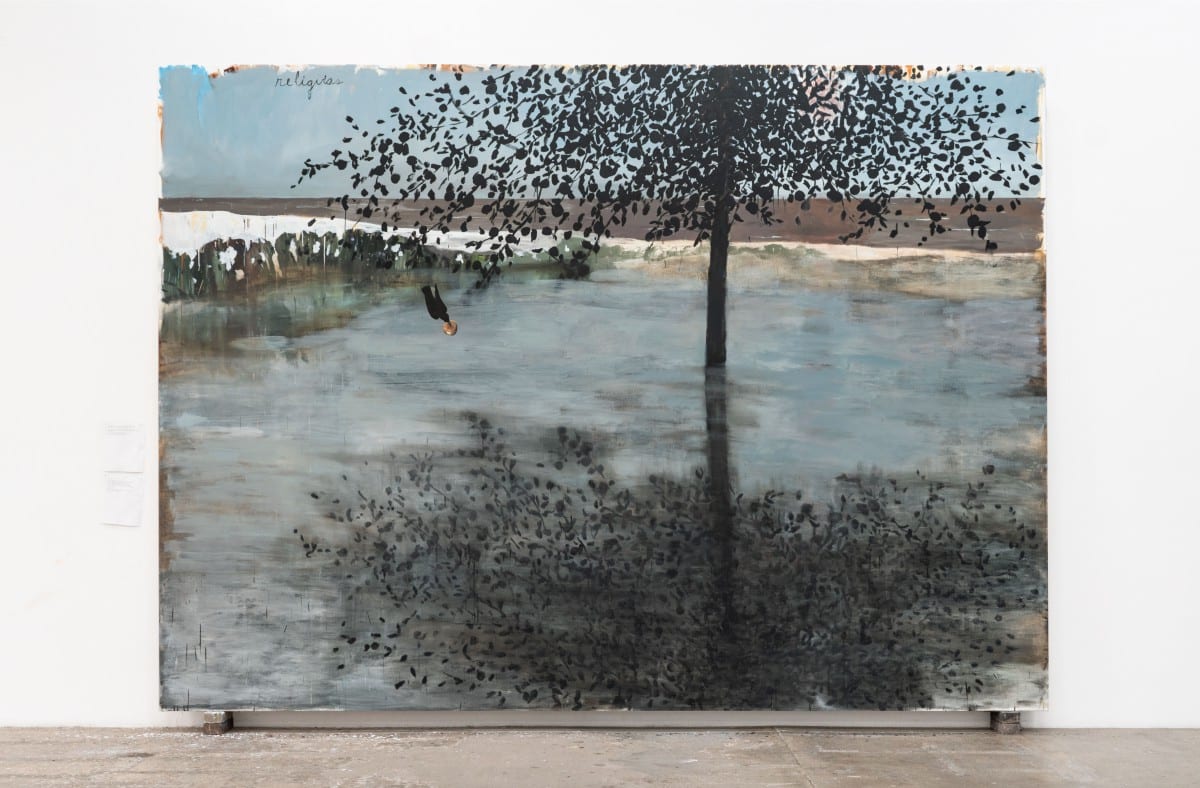

“At this stage, I have been writing and thinking about what’s going on without trying to control it,” Martínez Celaya says standing with half his body facing the painting and the other toward me. He contends that “The Promise of the Most Whole” and much of the works in “The Tears of Things,” are more focused on “the land, and more about the journey, and risk and transformation,” while the sea was a dominant motif in “The Mariner’s Meadow” at Blain|Southern, London. Presenting the roaring ocean in shades of gold, the painting titled “The Second Sign,” is a continuation of the artist’s preoccupation with gold. The terrain has shifted from the water to land which sparks the question for Martínez Celaya, “what happens when the entire landscape that you are engaging with seems to be transforming into gold?” The color gold can be considered an allegory for painting- the presentation of a shining, glistening surface that has risen from the ashes to serve as a beacon. However, there is a tension between the subject and the artifice of the surface. In a conscious decision, Martínez Celaya crudely renders the gold to suggest gold but also acknowledges the crudely painted paint.

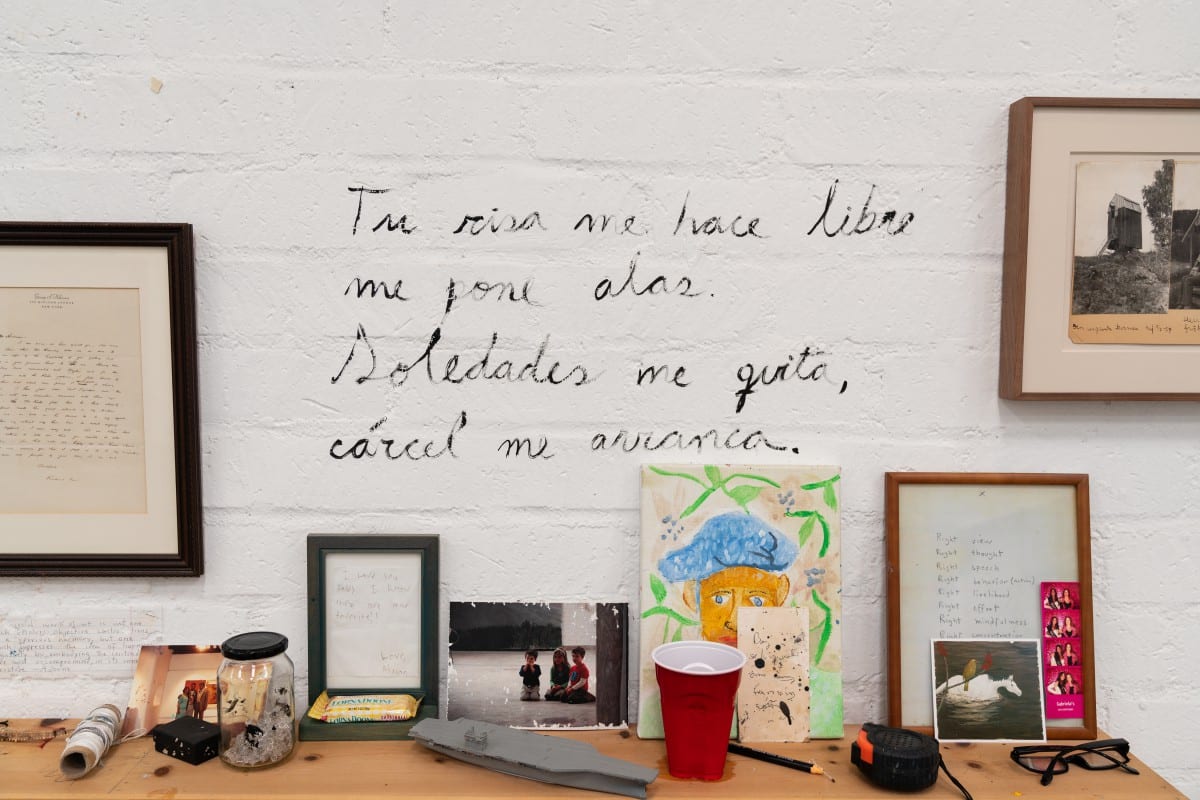

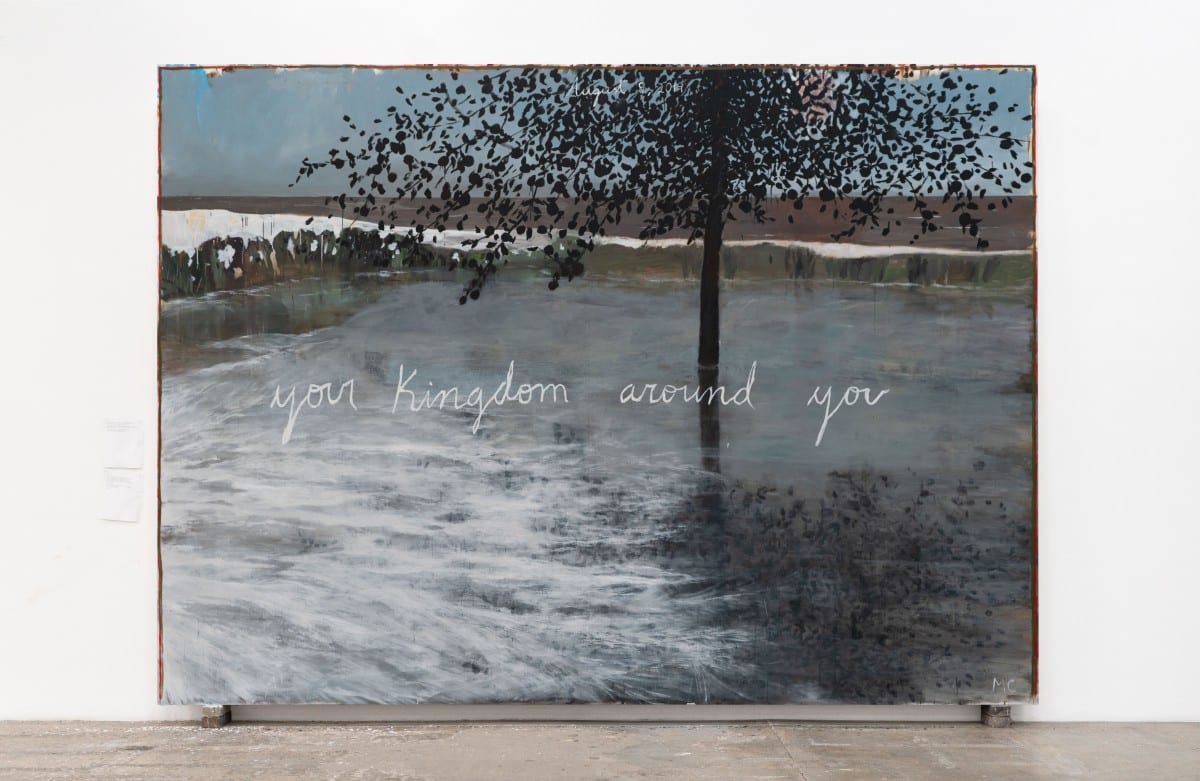

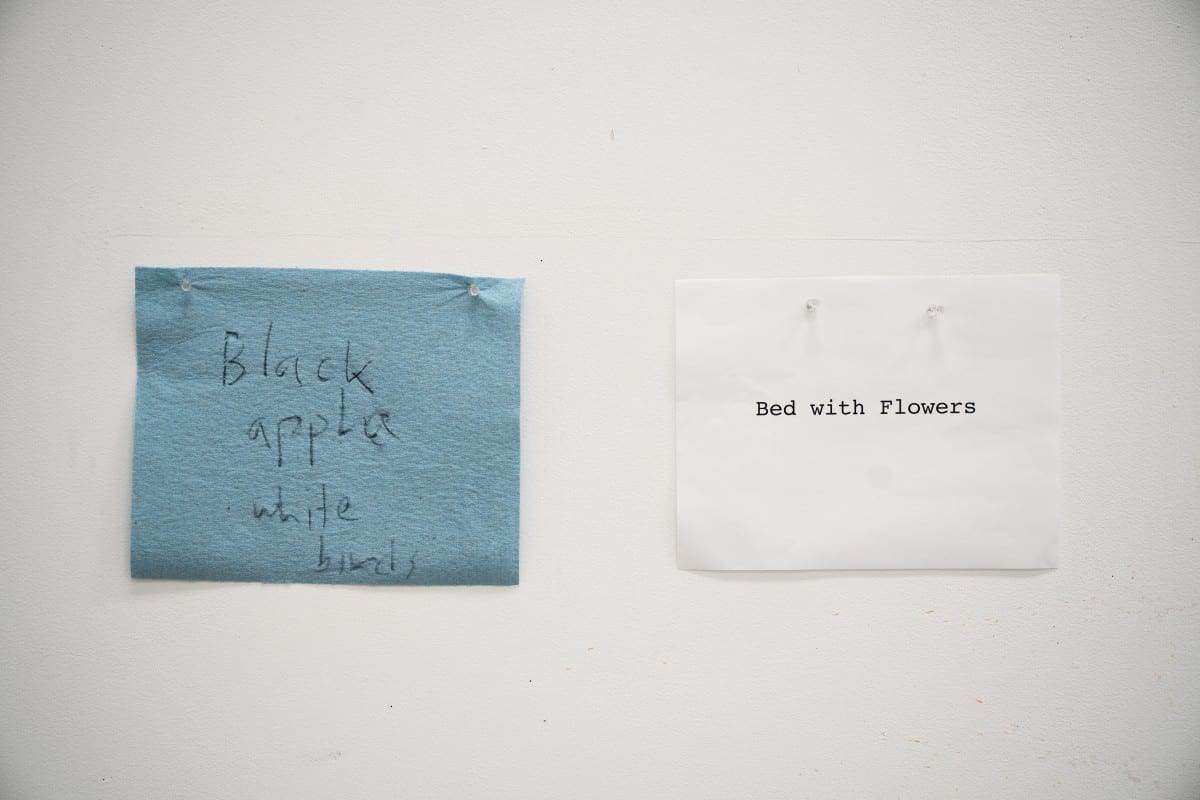

While writing is an integral part of his artistic practice, the subjects of each painting are rendered without reference to any source, just as a writer doesn’t begin in pencil to trace over selected words in ink. The paintings undergo a revision just like a piece of writing. “There’s a lot of writing in my notebooks and I have this desire and hope that there will be a lot of text in these paintings when they’re done,” he says while mixing more auburn shades into the golden trunk. “I still haven’t figured out why it is that text appears sometimes early and sometimes later,” he explains. The paintings are often inscribed with words and this weight makes them feel like poems as Martínez Celaya suggests, “I think that sometimes it feels as if the paintings are poems anyway because the aspect of space between words is so important to them that they should be considered poems in themselves.” The narrative of his poetic paintings often shifts depending on who is reading the works, especially because Martínez Celaya’s personal story references turbulent cultural climates in his native Cuba and upbringing in Spain and Puerto Rico. To achieve autonomy from his work so that they are not dependent on his story and symbols, the artist commits to making his actions faithful. Painted in the artist’s light cursive hand, the same message appears on the highest point of the wall, looking down onto the studio space below. Looking up at the message the artist explains that “the idea is that your actions and your words will be the same. If I am saying something to you and the moment you leave I am acting completely different, then that’s kind of a lie that not only destroys you as an individual but destroys you as an artist.” Pointing to a table on the opposite end of the gallery, the artist refers to the photographs and objects placed along the wall. “None of those things are mementos,” he insists. “They look like they are, but they are not. They’re all rulers by which I measure my behavior,” he states after smudging the canvas with a blue cloth.

The natural light flooding into the studio from the high ceilings and skylights. Image © Rainer Hosch.

The Making of “The Well,” video © Robert Wedemeyer and EMC Studio.

Image © Robert Wedemeyer and EMC Studio.

Image © Robert Wedemeyer and EMC Studio.

Image © Robert Wedemeyer and EMC Studio.

Image © Robert Wedemeyer and EMC Studio.

Image © Robert Wedemeyer and EMC Studio.

Image © Robert Wedemeyer and EMC Studio

Image © Robert Wedemeyer and EMC Studio.

Image © Robert Wedemeyer and EMC Studio.

In his writing titled “The Tears of Things,” Martínez Celaya addresses that the paintings and sculptures in his exhibition “revolve around three dualities- our alienation from and interconnectedness with all that there is, the absurdity and redeeming possibility of embarking, and the tension between promise and risk.” The theme of alienation or exile is a common note that many read while studying the artist’s works. While waving his paintbrush like a maestro conducting the deliberate cadence in his voice, Martínez Celaya explains that “it’s become very hard not to have it be part of the narrative and part of the conversation. The sense of exile which people want to talk about all the time.” He looks at me and asks, “who is not in exile?” I hadn’t considered the otherness I had been feeling to be worthy of note but he continued, “who is not in exile from family, in exile from the common idea of “you belong here?” How many people feel outside of that and outside of themselves?” As the words echo, I look down at my shirt and see the familiar Kriah, a black torn ribbon I have worn for the past thirty days while mourning the loss of the closest person in my life. I silently raised my hand that I too was in exile.

The inspiration for the title of Martínez Celaya’s Los Angeles exhibition arrived when he was re-reading “The Aeneid.” He writes that he encountered the passage in which “Aeneas, the Trojan hero on his way to founding Rome, observes a mural depicting the battle of Troy. A shaken Aeneas said: “sunt lacrimae rerum et mentem mortalia tangent,” whose most moving translation is “there are tears of things, and mortal matters touch the mind.” The determination that the mind is as fragile as the mortal flesh inevitably creates the “tears of things,” and so Martínez Celaya seeks to preserve the ideas which keep him faithful and the ideas that fuel his practice.

In the visions and revisions made on the page and canvas, Martínez Celaya becomes a messenger capturing the fleeting present and realizing it in a more permanent form. By painting, sculpting, writing, teaching, and publishing the artist anchors the truths that guide him and the ideas that he wrestles with. “The Tears of Things” delicately holds onto the precious moments of the past so that they do not recede further into the darkened corners of one’s own mind, but instead become a new territory to explore.

Enrique Martínez Celaya: “The Tears of Things” at Kohn Gallery, Los Angeles on view 13 September – 1 November 2019

Photographic documentation of paintings in progress and completed and video © Robert Wedemeyer and EMC Studio, 2019

Photography of the artist and artwork captured during a studio visit © Rainer Hosch, Installation Magazine, 2019

Discover our first (two–part) interview with Enrique Martínez Celaya discussing his solo exhibition “Lone Star” at LA Louver