There are several raw canvases that have been stretched by hand, drying on the lawn in the mid afternoon sun. Several overturned, empty white gallon buckets support either side. A makeshift assembly line that would only be possible in Southern California. Seated outside of his converted garage studio, Miller Updegraff wrings his hands, stained from the knuckle down with a dark blue ink. The studio was sparse when we visited because a majority of the work had been shown at Art Los Angeles Contemporary, which is where Installation encountered the artist’s work for the first time. Like an image bleeds into the tissue of memory, Updegraff’s paintings employ the effect of an aging photograph that allows us to look back before the image fades.

Installation Magazine: Your work has a definitive point of view in terms of palette. How did you develop this approach?

Miller Updegraff: My initial concern was to totally pull back and essentially bleach all color out of it so it all becomes about form and composition. I didn’t want it to be a registered black and white work so there are certain subtle colors that come through. There’s never black but it’s something sort of close to it. I have found that using different materials, inks, acrylics, paints, different brands how they separate even when combined and mixed well there is a dispersion that happens.

You reference archival, found photographs but I imagine the age of the photographs might influence the color scheme. The photographs are a result of time and chemical fighting against each other.

With the old photographs I started thinking about the relationship between the way in which they age over time and how information gets lost, but there is still the opportunity to register what’s left. There’s that physical response to the object and then there’s this emotional response and I don’t know if it’s an epiphenomenal thing. The deterioration of the image will affect the way that painting is made and will evoke a sense of nostalgic or the romantic presence of something past, or the idea of longing.

Do you choose to exclude information?

I have a devout relationship with the amount of time it takes to make a painting. One thing I have become very interested in was how much information the eye needs in to understand what it sees. How many marks does it take to recognize the subject, to create an optical illusion of presence? How much agency do I have to then give to you the idea that you’re looking at something and potentially have an experience with it? I read somewhere that humans have an ability to regard something in the physical environment, register it, and move on within nanoseconds. We also have a blind spot in regards to painting. In the absence of enough marks, of enough information, the image falls apart before you. The idea of limited mark-making and the idea of the nostalgic experience was interesting to me in tandem: how much information do have to include to produce the response? The interior self responds to that which is seen.

Describe the use of materials to our readers. You are working with a neutral palette but there is a distinct sheen on the surface of the canvas.

No one ever asks about the glitter. It has to do with opticality: stopping the viewer long enough. It’s an assumption of depth that changes with the light. It’s trickery. In terms of the canvas, I need it to be raw. I don’t want anything on it and it’s just where I’m at right now. I used to paint on gessoed stuff and pre-fab and my MFA show has loads of pre-fab Fredericks canvases in it (laughs.) Now, there’s no gesso, there’s nothing to cover a mistake. If it’s screwed up, it’s screwed up. Then you start over.

Are you curious about a specific time period or is it the composition of a photograph?

I’m interested in being able to bridge the gap from anthropological research. But with anything in life, I firmly believe that we have a quite shaky relationship to existence and the ability by which I can give what we’re doing right now meaning forms a bridge over the abyss of existential nothingness. So yes, there is a sense of history and research but there is also timelessness.

A unifying theme in painting and photography is the gaze and by way of course, gender roles. Your decision to paint male subjects presents a rich duality- on the one hand you acknowledge your position as a white male who inherently possesses the power of the gaze. On the other hand, you’re aligning yourself with your subject to establish equality.

I’m interested in discerning my place in the world, and it never gets easier. I always felt like a human but I never felt like a male or female or whatever. At CalArts I posted ads on Craigslist or community bulletin boards. Most were answered by guys. I’d been interested in the role of men. I’m a white guy. My position of power within the patriarchy is explicit. But if I turn my gaze onto other men, I’m not necessarily affecting the power balance at all, it’s more egalitarian. All I’m doing is sort of bolstering that same position. At the time, I felt I was giving the subject more agency. But it’s stupid- I am still the artist, I have control over the vision in the end. In that model, I am just as anthropologically imperialistic or than the artists I had refuted in grad school. The emotional connections I made with my subjects also became too intense; after two and a half years, I made a conscious decision to stop working this way.

What made it emotionally intense?

As an ethnographer there’s a participant-observer problem: how close can I get to the material where I can still look at it objectively? I decided that I couldn’t give these subjects the agency to honor them.

How is your current practice more manageable emotionally and how does it play into or subvert notions of agency and the gaze?

It’s a lot about historical periods that what I respond to. History is a blind spot now and it’s not that long away; it’s germaine and it holds meaning for me. That’s all it does. A good science fiction story gives you a new perspective about society because it provides distance, it lets you step back and see things in a new way. In the same vein, I started researching history, and these things became stand-ins. I project myself into it, watching from a ways off and maybe longing for something. The content of the work is not specifically the image itself but the emotion that it evokes in me. This is what I’m not telling the viewer.

Does the voyeurism translate into your everyday life?

Oh yeah. If I could be a disembodied eye I would be extremely happy. I am much more comfortable receding and watching, although that may surprise some people.

Though you have representation in both LA and NY, you live in LA. Did you come to LA to attend CalArts?

I had been here for a couple of years prior. I had been thinking about art school but I didn’t know where, I just knew it would be LA. There’s a the sensibility: if a place has a personality, I guess LA’s would be open. It’s the right feel.

Who are your influences?

I love the way that de Kooning handled paint. There is a lusciousness, I’m not saying that I try to affect that with what I do, but my god it was like cheesecake, you just wanted to eat it. Hans Hoffman had a way with pigment. I’ve realized that while the work I do is kind of limited in color, the artists who lead me to painting, in general, are all about colors that you could slather all over your body.

What about Francis Bacon and his series of Boxers?

In Bacon we could find more of a bridge, maybe, in their physicality or what’s evoked by it. I’ve definitely I responded to Bacon but his work has always felt a little too close to my own depressive nature: I couldn’t handle it for very long. Some people hit a little too close to home from an emotional standpoint. I sort of need to find an influence like Bacon, but with a bit more humor. Which in some ways I sort of try to imagine someone like de Kooning having, although maybe he didn’t.

I don’t know how much cinema influences your practice, but there is a sense that you are a camera taking on these still images, channeling them onto a new surface and space to project memories, longings, and hopes.

I had a professor in grad school who said ‘you’re artist as computer.’ My work dissects information but does not give a sense of hierarchy. It’s more like artist as filtering system. While I am honoring the subject, I am all brush.

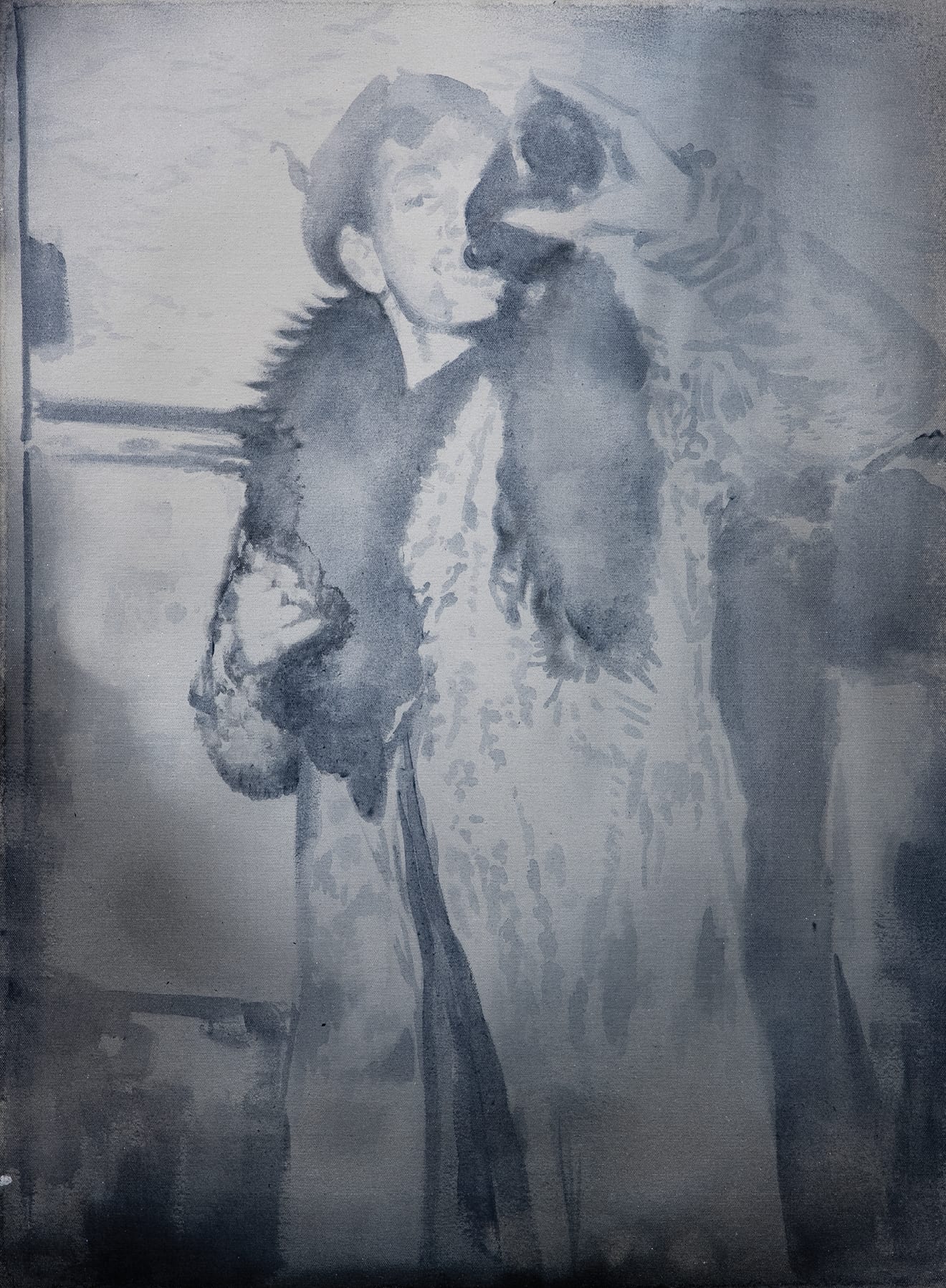

Featured image: Miller Updegraff, I have no name, vintage watercolor pencil on Arches paper, 17 3/4″ x 23 1/4″, 2011

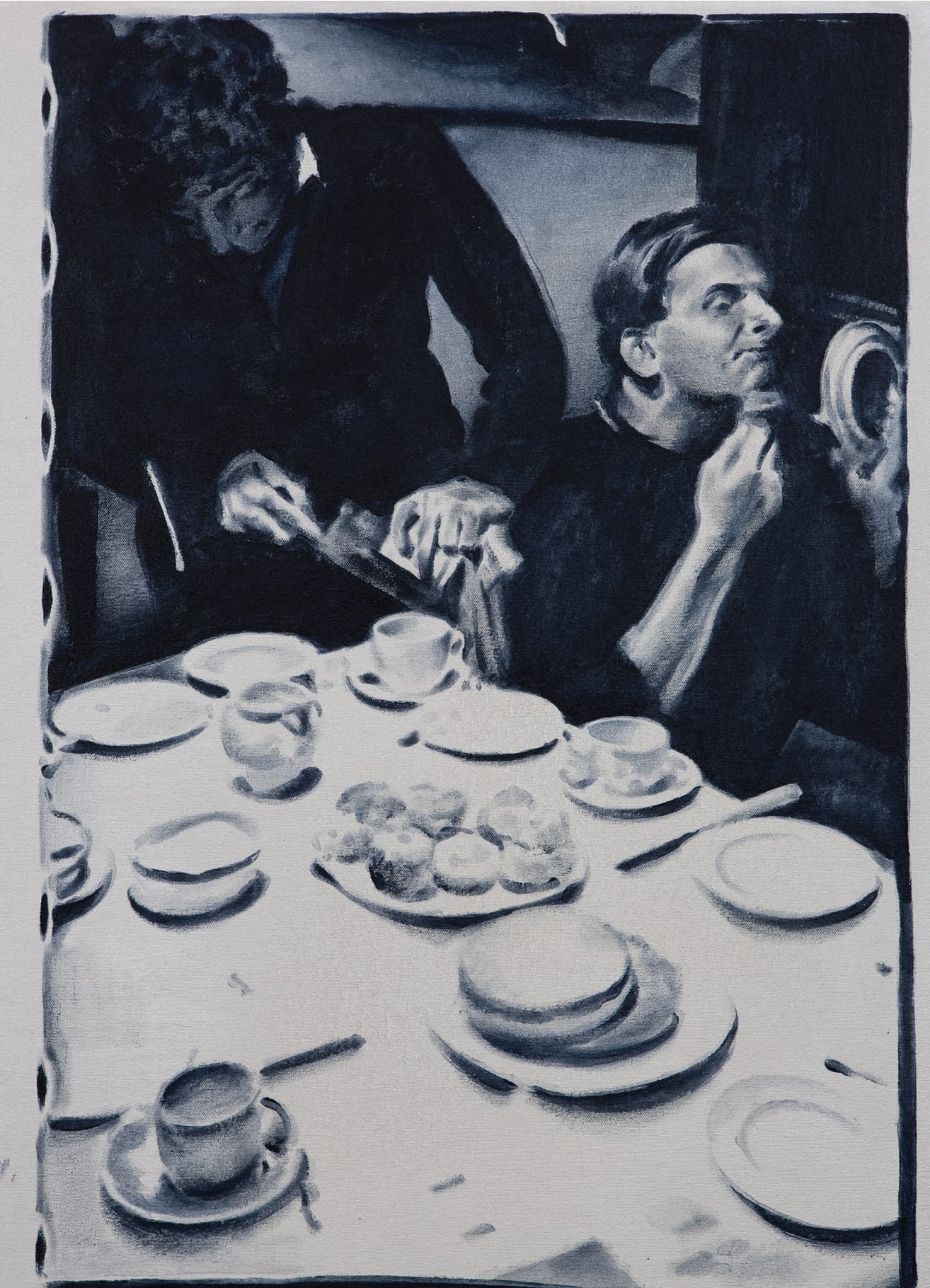

All images © of the artist