Anya and Andrew Shiva Gallery present the works of Allan McCollum, Andrew Ross, Carin Riley, David Goodman, Felipe Cortez, Frauke Schlitz, Kara Rooney, Lan Tuazon, Lauren Clay, Paul Anthony Smith and Willaim Corwin in the group exhibition “Politicizing Space” in their primary fine art gallery at John Jay College of Criminal Justice. On view from February 2, 2017 – March 31, 2017, the group exhibition curated by Charlotta Kotik examines the dichotomy of power between the art object and viewer.

The architecture and art of the urban space can be used to control the lives of the city dwellers; they can restrain and contain their movements and embed a received history and chain of hierarchies beneficial to those in power. The eleven artists in Politicizing Space critique and subvert these purportedly aesthetic and artistic gestures by reinterpreting the symbolic mechanisms of control and asking the age-old question about the balance of power between art object and viewer. These artists address the allocation of space and the reasons for and the consequences of space distribution and control. Occupying space is a necessity for sculpture and installations and architecture—in claiming a portion of a particular area the three-dimensional work deprives us of the section of space we tend to see as “ours.” From that competition arises the question of the intentionality of the architecture, installation or art object: does it seek to engage the viewer on an equal footing of open dialogue or does it seek to talk down and manipulate? Chain-link fences, cinder-block walls, equestrian monuments, and caryatids are one-sided objects, they instill mythologies and fear and are not particularly open to discussion, but they can be scrutinized, caricaturized and reinterpreted.

There is the pure visceral response to sculpture and installation—in which grows a tension—we have to react to the presence of another entity and to adjust our behavior to make cohabitation possible. This tension leads us back to the conundrum of allocation and control of any given locale which has been the source of the most violent and politically motivated acts in human history. Nowhere is the possibility of confrontation more palpable than in the urban environment where multiple forces collide and compete for the limited amount of precious space.

The chain link fences in the work of Paul Anthony Smith are a direct reference to the intent to posses and to control. The formal beauty of the presentation only underscores the clarity of the message – there is a mortal danger in trespassing or any other attempt to usurp part of a “claimed” space–the sociological separation between the haves and the have-nots is made manifest reality by the very real presence of an effective but seemingly insignificant filigree of intertwined wire.

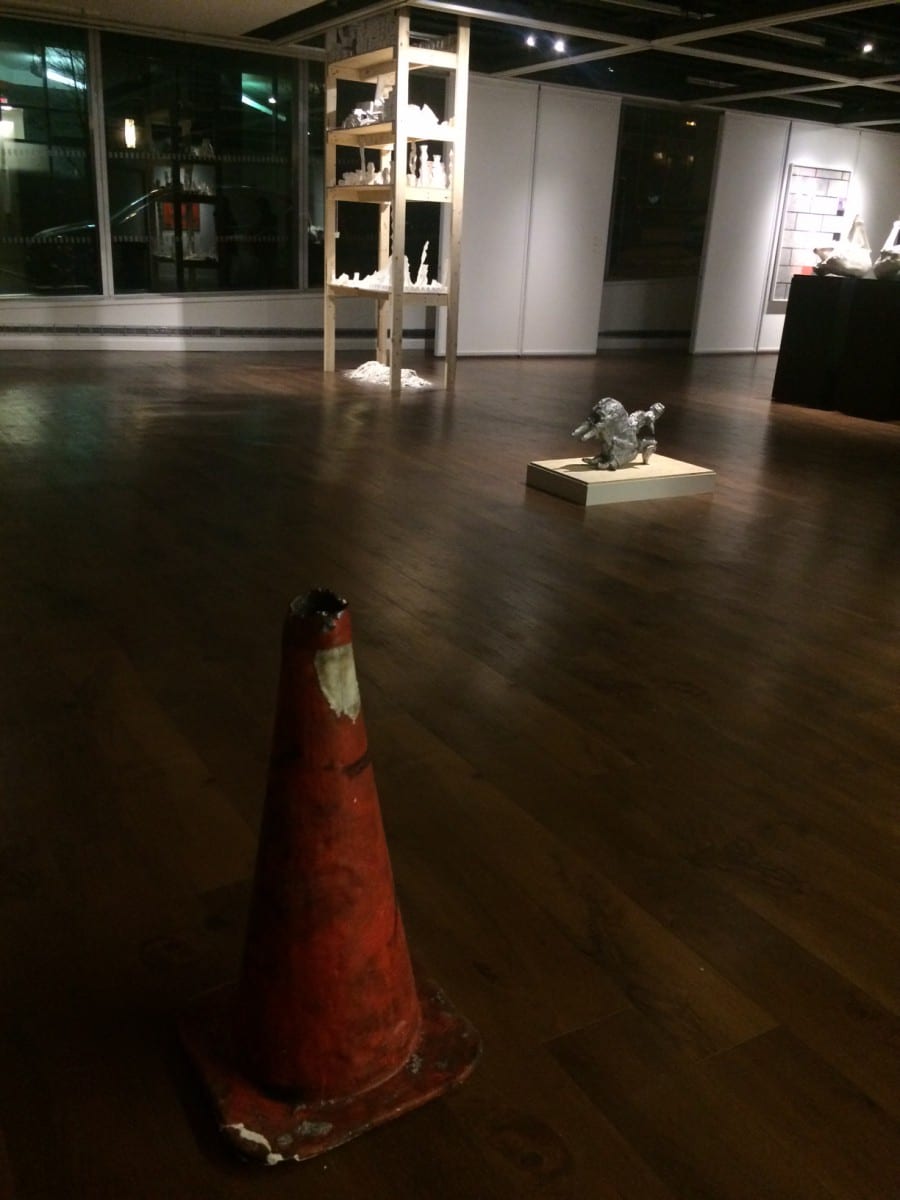

Similarly, the traffic signs and street cones in the work of Filipe Cortez deal with places which we are forbidden to access and the ease and simplicity by which the paths and movements of urban residents (and non-urban residents alike) can be manipulated and controlled. Another of Cortez’s series alludes to both destruction and renewal in the urban environment. Many of his works from the Ecdysis Series (2015/16) are visualized “memories”, vinyl imprints of sections of buildings assigned for demolition or radical reconstruction; reflecting the ever-changing character of urban dynamics.

The city environment can be harsh and defensive; implements both physical and legal (i.e. the institution of property and real estate) are created to guard the possession of space. These real and imagined tools are referenced in the work of Lan Tuazon. Her series Architecture of Defense transforms fences, gates, and locks into aesthetic units that underscore the antagonistic relationships evolving from clashes over the control of a particular location. There also exists seemingly empty spaces, harbingers of the future land grab, eminent domain and gentrification—frequently found in the form of parking spaces. In the series Parking Lot Landscapes (2010), Tuazon addresses control through property. Public or private parking spaces are some of the prime possessions in the city’s structure and as such are also an embodiment of ownership, reservoirs of money and power, and a source of frequent strife.

Nowhere is power expressed more acutely than in the equestrian sculptures serving as the symbolic apex of public spaces worldwide. Commanding space from above, placed on pedestals to magnify the distance between mortals and the ruler/hero these sculptures are intended to express might and control over space, over the populace and to inculcate a particular reading of history. However, the ruling powers are frequently subverted by the course of human events as in the case of the ill-fated gilt-lead sculpture of George III on horseback at Bowling Green in downtown Manhattan. In the work of William Corwin, Poor Dead King (2017), the lead form, diminished scale, and trajectory of collapse of a 1/8th scale replica of the Bowling Green monument is a parable of the fall from power of many monarchs and other dictators, not only this one particular vain, ineffective, and unstable king.

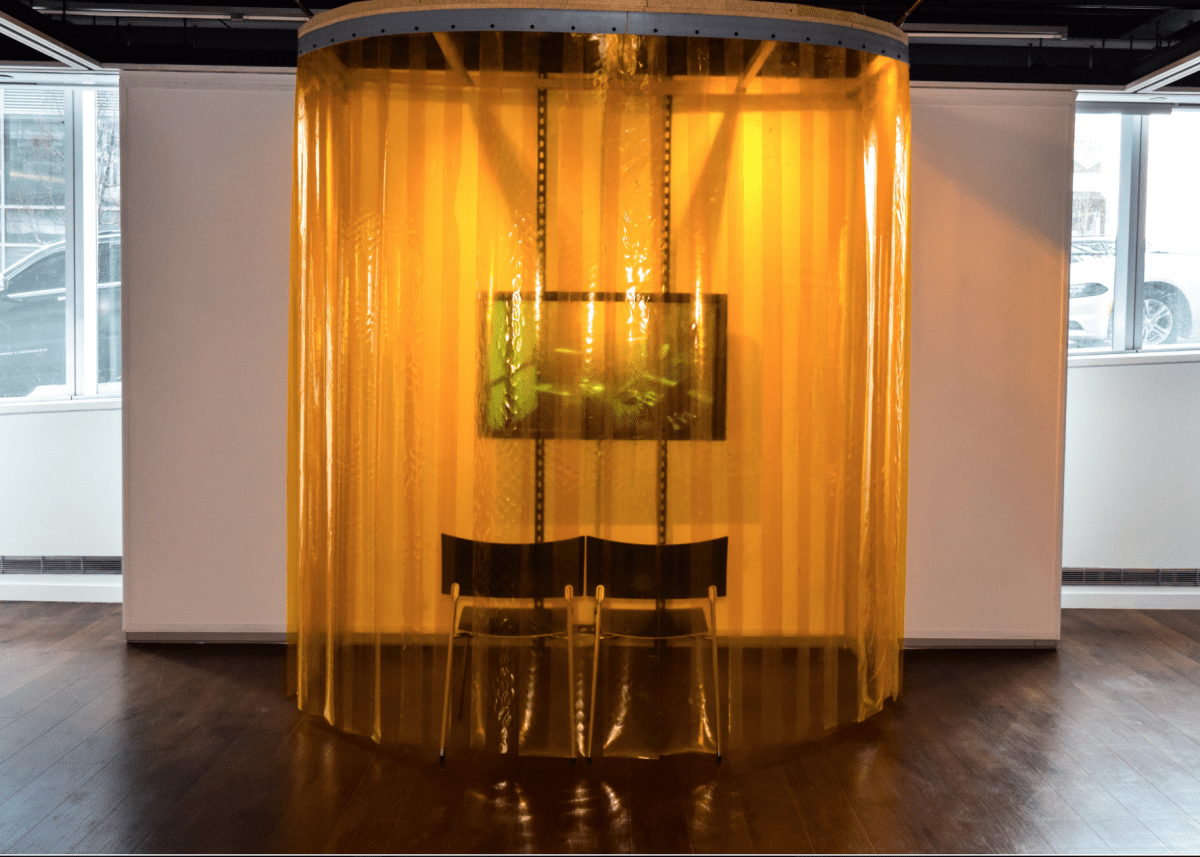

Complementing the look from above of the empowered is the view from below: the unenviable position of living underground, and finding or creating a maze of spaces, the most basic primal structure existing for sheer survival. Andrew Ross’s Secret Lives of Mole People (2017) addresses the issues of subsistence and total disenfranchisement, and more importantly the rhetoric of the demonization of “the other.” Ross draws specifically on the Zombie Apocalypse—a fear-mongering bugbear of the white supremacist Alt-right movement, signifying the chaos accompanying the empowerment of minorities in America, as well as contemporary sci-fi imagery. He also employs Maia and other animation software to create virtual sculptures and installations.

Curiosity may have doomed the feline, but servitude and obedience killed the dog. Chained in the entryway of Pompeii home when Vesuvius erupted in 79 AD, a dog struggled and ultimately asphyxiated under layers of fine ash that in turn perfectly preserved the shape of its body. As the organic material disintegrated, the form became a mold that allowed for a cast to be made of the tortured animal. Allan McCollum’s The Dog From Pompei, 1990/91, is a cast of the original cast of the dog. While not specifically commenting on class, the dog has come to epitomize the devastation of a cataclysmic disaster in an urban environment. It represents the plight of individuals that have nowhere to go imprisoned by chains of poverty. The Dog From Pompei also expresses the helplessness of living beings caught up in ecological and environmental disaster, man-made or otherwise.

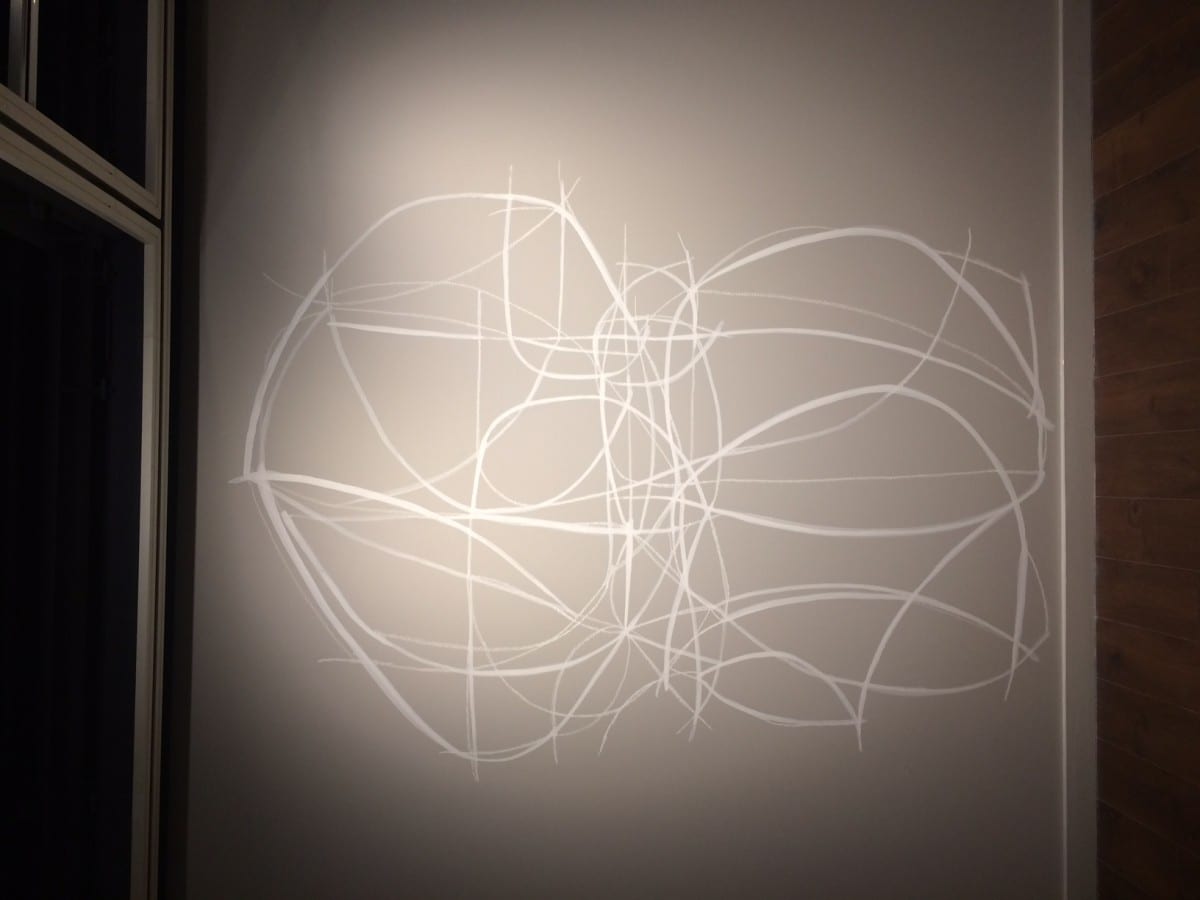

Several of the artists make references to classical and pre-modern art tropes. Carin Riley’s Caryatid Wall Drawings (2017) reference the sculptures of female figures used in classical Greek architecture as structural support. The support can be seen not only as architectural, in a larger sense it also functions as a metaphor of both female strength and subjugation in Ancient Greece. The specific caryatids Riley draws upon are from the façade of the treasury at Delphi, guardians of the wealth and sacred objects of the city. Riley transforms them into two-dimensional diagrams, toying again with the implications of structural integrity and power-both symbolic and real, and the position of the art work as both permanent installation and ephemeral sketch.

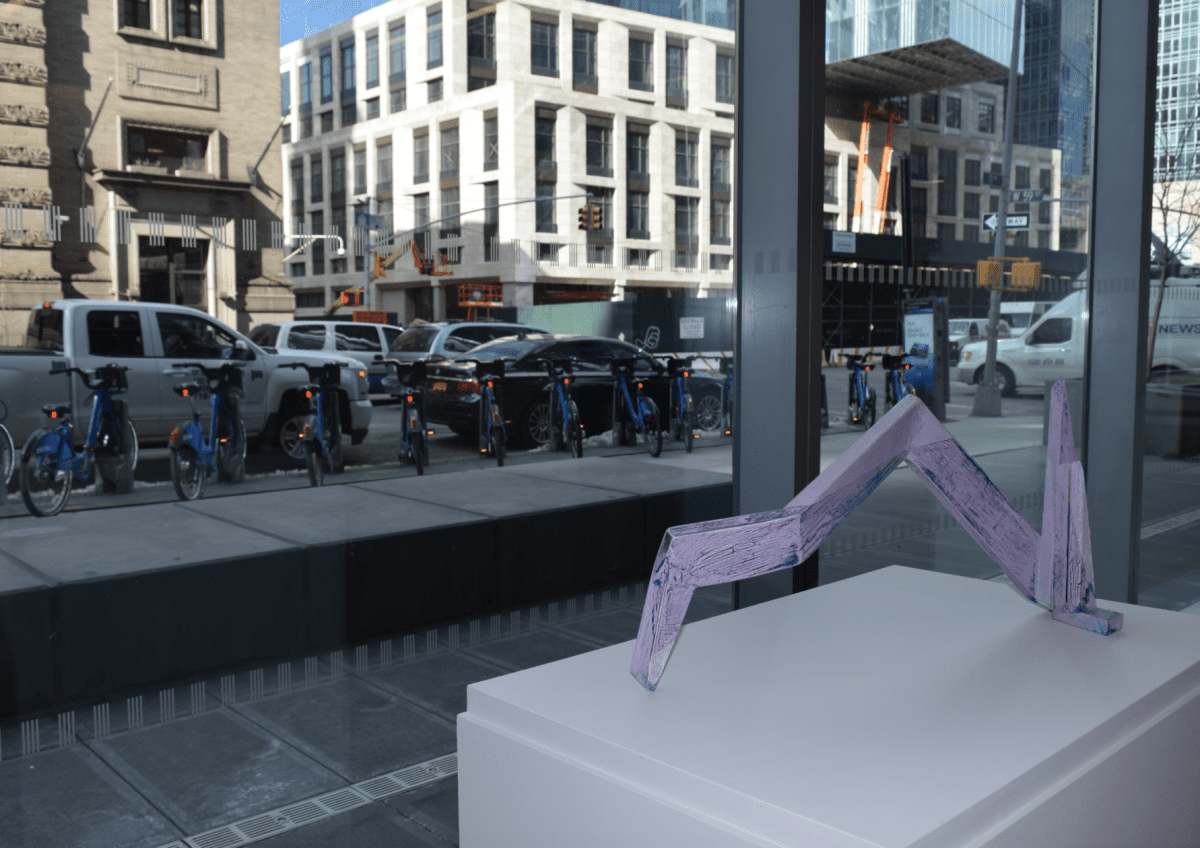

Similarly, the interest in classical themes of balance and symmetry informs Reverb No.13, (2013) by Kara Rooney. Her pieces are guided by probing into history, theories of linguistics, and a keen appreciation of philosophy and literature, especially poetry. She sees these as influential on the formation of personal and collective memories and as facilitators of our perception of the world. Titles of Rooney’s series can clarify and obscure the meaning of her pieces simultaneously. Alter No. 5 (2016) alludes to a legitimate historical altar hung vertically, however, Alter No.3 (2015) is collapsed on itself as if faith has given way to ever flowing doubt. It is confrontational, as it forces us to navigate around it and to acknowledge the fragility and the perpetual altering of opinions, ideas and culture itself.

David Goodman’s Monolith (2017) deals with properties of painting as well as sculpture and with scale that reaches architectural proportions. He both highlights and subverts the commonly accepted properties of varied mediums—the sculptures utilize two-dimensional color schemes to invent false volumes within the real massing and volume of the object and to reassert the object’s place in space as well. Though hollow and directing the viewer towards no orientation in particular, nevertheless it claims space in way analogous to a monumental entryway, and engages the concept of the monument, the triumphal arch and the gateway as vehicles of a particular narrative or agenda, both attempting to control the collective unconscious of the city and direct its citizenry.

Work of Frauke Schlitz investigates the phenomena of space, architecture and topography and the relationships that develop while we perceive, or mentally navigate, through man-made spaces Our perception of space is guided through systems of geometries that seem to graphically and conceptually sustain given spaces. Schlitz sees the mathematical reductiveness in her work as a kind of grammatical scaffold from which the meaning of the space and our perception of it could be derived. She engages the metaphor of the gateway and plays with its unconscious attraction to the eye, while also raising the question of where exactly it is we think we are going.

Lauren Clay, like Goodman and Schlitz, directly engages with architecture. She generates surrogate surfaces by enlarging marbleized pigment patterns and laminating them onto existing walls and architectural details. Subtly subversive, Clay’s swirling textures imitate marble but push beyond what we find comfortable. The wall and existing architecture are transformed from a two-dimensional entity into a panoramic vista full of twists and turns of an almost psychedelic and chaotic nature. The patterns reject the orderly division of space and the comfort of the habitual and the status quo, instead, dissolving structure and hierarchy in favor of random abstraction and freedom of form.

It’s a cliché to claim political urgency when prefacing an exhibition of this nature, but the current political climate is one of extreme self-mythologizing and insistence on acceptance of received histories bearing little or no reference to actual history or data. With increasing frequency, we are seeing the return of architectural and urban strategies that reinforce class structures and the status quo of inequality, as well as streams of propaganda strengthening the cult of personality of the dictatorial and suspiciously elected patron saint of the bigoted and the moneyed classes, the charlatan Donald Trump. Events in the twentieth century remind us that politically minded contortions and suppression of the once thriving metropolis is not a situation relegated to ancient history.

If we are not vigilant in the pursuit of the rational management of resources and the suppression of aggressive behavior, a similar fate may befall cities worldwide as they are some of the most vulnerable entities constructed by mankind. By artfully reimagining what might otherwise be seen as a dark and inevitable conclusion, we can find possible avenues to salvation.

– Charlotta Kotik, Brooklyn, 2017

All images courtesy of the Anya and Andrew Shiva Gallery and the artists.