The bull horns have followed Gregory Siff to every studio he has ever had. The horns both signify the beauty of nature’s ferocity and channel the past in subtle whispers. Over the years, the horns collected the natural debris of airborne paint particles before they dried, continually charged with the energy of ideas developed day in and day out.

From West Hollywood to Downtown Los Angeles to Glendale and now Sunland, every studio had a unique floorplan, but no matter the square footage, there was always a space for the bull horns. Mounted across thresholds, carefully placed along the crease where the wall meets the ceiling or occupying its own space on a large wall with room to breathe, the horns were always coveted as a holy object, a traveling totem that, once mounted, meant the space had shifted from a sterile white cube into an incubator of dreams.

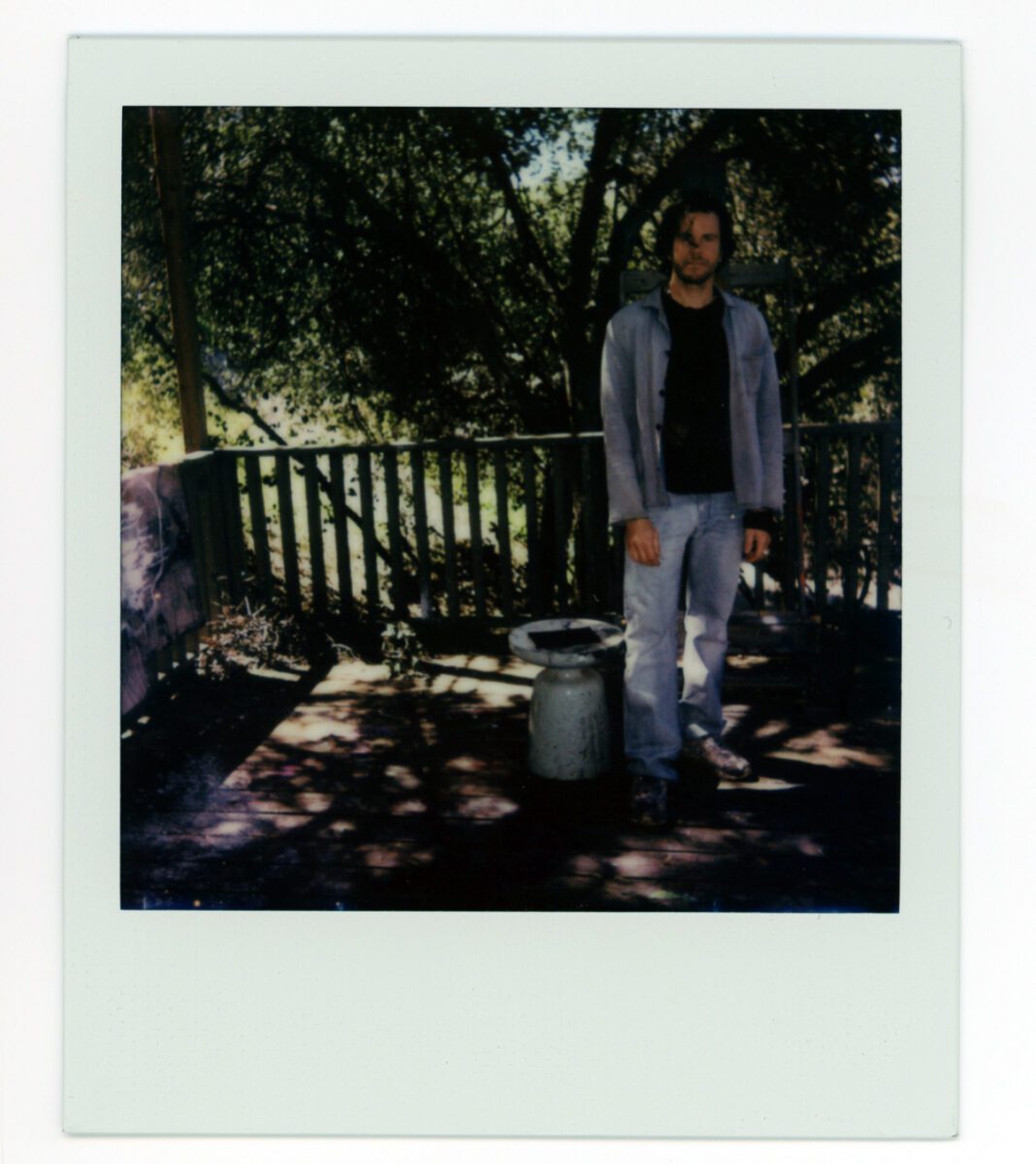

Photograph by Rainer Hosch

Photograph by Rainer Hosch

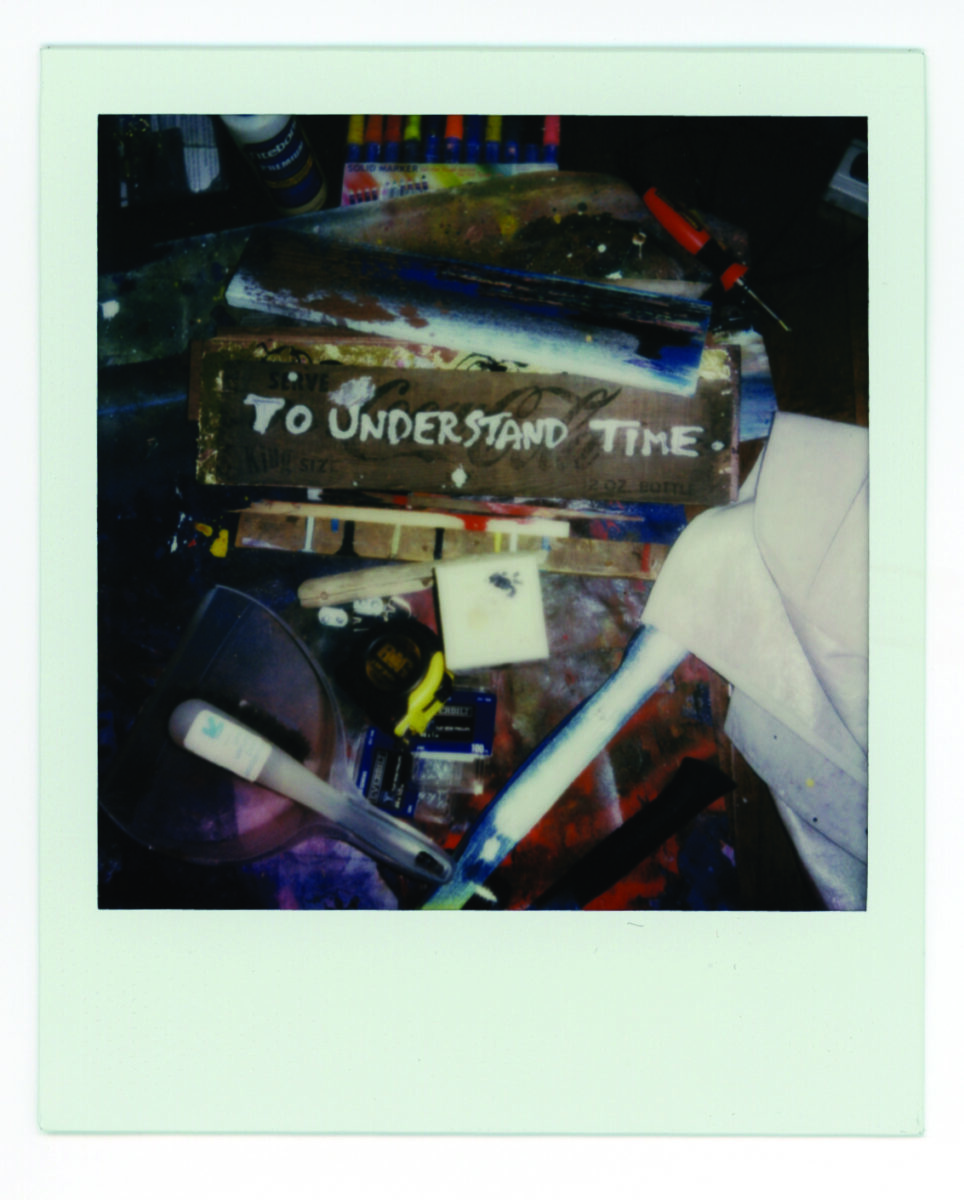

Other mementos were never far, including handwritten notes from Gregory’s mother, a circular wall clock with a partially cracked face bearing the letters “T-I-M-E” written across with the signature Krink Ink drip style. The artist further customized the clock, with its numbers on the face repainted and its batteries intentionally removed so that the hour and minute hand never aligned to the time of day beyond the studio walls. TOPPS baseball cards, tubs of original Bazooka bubble gum, and wood crates labeled with the materials contained would line shelves and spill over onto the floor. Paint brushes held upright by sheets of styrofoam, wood crates containing crayons, markers, oil paint, spray cans, and “big ideas” were strewn across the floor like a constellation unique to the universe of Gregory Siff. Every tool had a place and was cataloged in Siff’s photographic memory, always ready to be called upon when needed.

A guardian of the studio, a surveyor of the process, a faithful companion listening to the pencil sketching ideas, the first stroke on a freshly stretched canvas, the bull was always at the core of the creative space. The hours have turned into days, and the days soon into years. The bull horns on the all echoed the bull that had always been inside the artist’s heart and hands his entire life. A gold cast ring that belonged to the artist’s late father is always on his finger. His hands, like his father’s hands, in the constant practice of an exercise of the sensory and the visceral, guiding the creation of symbols and the invention of a language that makes the abstract memories become fully realized into dimensional artifacts forever suspended in the muscle of the heart.

Photograph by Rainer Hosch

Gregory Siff’s solo exhibition, “To Understand Time,” is dedicated to the artist’s late father, whom he lost at the age of 29. The date is also of significance as it’s the same day on what would have been the Dutch Post-Impressionist Vincent Willem van Gogh’s birthday, 171 years ago. After a decade of practicing and perfecting a codified library of symbols, Siff has created his own visual language and oral history. The rudimentary symbols began with a brief lexicon- the handsome face, the ice cream cone, the rocket pop, the marshmallow, the magic mushroom, and the bull. While his father has always been present, this is the first time that Siff has distilled, clarified, and identified what it means to live with loss and reconcile years of missing and loving into a body of work that hits the bone. No, not just the bone. The marrow of the bone where life still flows. He has directed the clock from all angles, taken its mechanisms apart, and let words and symbols flow through him.

Photograph by Rainer Hosch

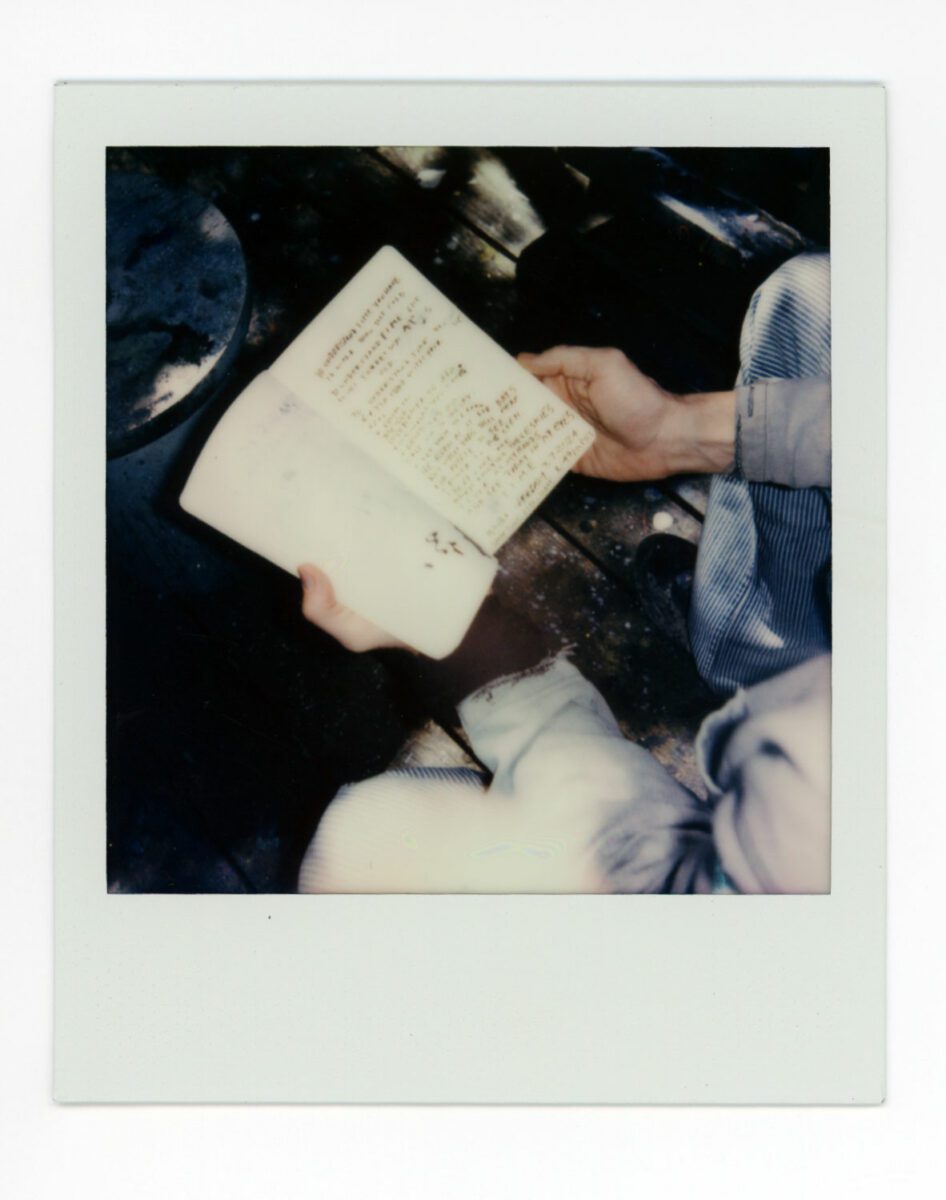

Ninety days were spent in the Sunland studio, creating a trinity of mixed media works called “Survival Markers,” mop brush paintings on paper bearing a new set of symbols and several large-scale canvases. I never had the chance to meet George Siff, but I feel his spirit every time I visit Gregory’s studio. His sensitivity to the world around him- the connection he deeply values with his family, the dedication to his work, a rigorous work ethic that ignores the need for a clock or a calendar. The wheels in his mind never stop spinning; they always capture and document moments in notebooks and writing. It is only now, after spending time with the works and listening to Gregory share dreams and poems written to his dad, that I felt the arc of our entire friendship come full circle. I was in the presence of a man who has spent his life determined to make his father proud and present the force of his spirit to the world in an exhibition that demonstrates maturity and mastery of material and mind.

Gregory Siff is a collector of treasures. A fierce protector of the sentimental. A custodian of objects imbued with family history, rich with stories that he remembers by holding them in the palm of his hand so that he could exhume every ounce of essence from the material, listen to each word spoken in a photograph, and even use his father’s pencil bearing the letters of his catering company “La Mer.”

The arrival of the title, “To Understand Time,” came after much deliberation, accompanied by vivid dreams and writing. Always playing with language, Siff saw “time” as an acronym for “Today In My Eyes.” We sit at the kitchen table while a single clock creates a heartbeat among the nearly finished works before they are designed and delivered to the gallery. Gregory opens his notebook and reads:

Today In My Eyes

To understand time

You have to walk through the cold

To understand time

One must forget what is old

To understand time

You’ve got to hang with your soul

And swim in the sun

Just moments ago

Find what you love

And never let go

Call out to the sky

And let them all know

I’ve been at it for days

But what does that mean?

For people to see

And powers to be seen

I feel like me when painting these skies

I look at my hands

And see today in my eyes

Your father has been a key symbol in your work since you developed your visual language. How did you know this was the time to speak directly to him through this exhibition?

I just started thinking about purpose and everyone’s purpose and story. I like this bond with someone that’s not there anymore. What are the remnants of someone who’s not here physically anymore but lives on the tongues of other people’s stories? I wanted that!

Now that you are at the end of this journey, guided by catharsis and vulnerability, do you feel a renewed connection to your dad?

I just wanted to hang out with him more and think about him more. My paintings look better when I’m thinking about him. Every art show I do is a coming of age. I don’t believe my age to understand time; it was just standing still for a second. Stand still. You look back a lot. And that’s why when I said in the poem, you’ll look at my hands like, there are certain things that I remember about my father’s hands that are in my hands, and I feel like we all have those characteristics that are that our parents or grandparents or lineage have left us and guess what? Everyone’s lineage is important. That’s what made me want to do it. I’m important. My connection to him is important enough to be on a painting.

“To Understand Time” is accompanied by three writing bodies. One manifests as a poem, the other as a dream, and the third as prose. Can you share what’s in your notebook?

I want to find my dad again.

“I want to sink my two front teeth into his tan leather back and run my pointer finger past that deep scar in his back that he got when someone stabbed him in the back.

I want to understand my life.

I want to be ready.

I want to remember that I am doing all that I can to get this out of me so we all can find that being.

I make things to find him.

The rest around me is the detritus of a kid uncovering himself until he is a man.

A giant beating heart writing with a pencil that my mother gave me- sailing with her forever on this ship to look through the butterflies and the mirror.

The movie star he saw has always been there.

I am only trying to find you through the paint-overs,

through the people

through the self-kindled happiness that is my face and who I state to be.

I hope I’m not missing out on me.

The tools used to create the works were restricted to an arsenal—a pencil that belonged to your father, a pencil that belonged to your mother, a mop brush, and a wide brush. There’s an alchemy of markers and paints used to create the canvases, but how did the tools reflect the story of the show?

For me, creating this brush, the mop brush, where there’s so many different spindles of fabric, so many different fibers of fabric, and the control is almost impossible, just how taking a rubber band and putting it like try my voice through new instruments, try my heart through new you know, take my heart on a ride, go to a different take a passport, and get it stamped all over the place and see what it looks like and not worry about what it looked like.

[The process is] It’s like a microscope, going deeper and deeper into the fibers of who my father is and who I am. … I’m just understanding the idea of letting something go.

I would love to hear you read your dream. Would you be willing to share?

I wanted you to look me in the eyes, I tried to tell you everything that was going on since you left here. The living room looked as it did when you were last in it. I sat on the white leather couch beside you, patiently repeating for you to look at me in the eyes so I can know it’s really you. You turned your head to the left and finally looked at me. I looked into your eyes, and I saw my blue eyes in your eye sockets. I knew at that moment you saw it all. I was no longer afraid of anything. You grabbed my knee with your grip like you always did, and with the voice of a force in the world, you said powerfully, now you’re cooking with GAS!

“GAS,” as the initials for George Abraham Siff

Survival markers are evidence of life. Traveling totems. Evidence of existence. Physical proof that the past happened

But what happens when our memories are so rich that we no longer need those physical artifacts around us to reinforce what we already know?

What happens when we reach a place where we can say goodbye to the physical and live fully with its memory, richness, and visceral nature very much alive in our hearts?

I tried to make my fingers a Kodak camera so you can see it. Each one has a canvas, a life force in it. It’s like the breathing part. Each piece makes me think of a person, a studio, a place, and a moment in time to connect my present life with my father’s voice and find remnants of things I’ve built and made. They live in the physical form. They live in my mind and heart, merging those two things together. They are phrases. They are things that I see as jagged beauty. They’re things that I’ve pieced together to create a jagged beauty that seems to be, but I don’t know how to balance them. But they come together to make one frame, slivers, and chunks of survival. I call them survival markers. They let you know where I’ve traveled and allow you to imagine what these mean; in the long run, it was very hard for me to stop adding signs and subtracting them as they watched me paint the canvases the whole time. I liked the idea of them being in the room, and having their own opinions about what I’m doing, and having their own pulses in the room in the studio; I would say they’re like having five best friends with you the whole time, I hope that they emanate that to the view to the viewer and in the same way have a moment of internal reflection for them to go into an interpersonal state of what they have collected in their lifetime and what they have to show for it.

When can we let go with a degree of certainty that will carry us into the next day? That moment can only be achieved when we’ve come full circle. We said what we needed to say. We shed the tears that have been long in the making, but we can purge ourselves. We need that room to start over; otherwise, it will be cluttered and disrupted with new memories.

We hold onto these survival markers to retain the physical connection from one world to another. We exhume their memories, channel their energy, and meditate when we don’t have a place to direct our prayers. They are evidence of a life lived. They are proof that the departed didn’t merely exist in a dream. They see us through the hours. When we’re trying to find our way and make them proud. Soon, we find that we rely less on the physical because the memory of the heart can feel it.

Those monuments

They belong to somebody else now.

Before leaving the studio, Gregory opens a video that was sent from his uncle in New York. A lost VHS tape from the mid-80s shows a beautiful party. Infectious laughter and love from everyone were captured through the lens. George Siff comes on the screen, dressed in a dapper and crisp suit, hypnotizing the camera with his blue eyes and boyish smile. He was the party’s heart because he knew how to create an environment where people wanted to be. He says with enthusiasm, “And the place is gorgeous!”

Gregory George Siff, you understand time now. You have created a new room, a new place, and it is gorgeous.

Photograph by Rainer Hosch

The solo exhibition “To Understand Time” opens in Los Angeles on 30 March 2024 and is on view at Praz Delavallade Los Angeles through 2 May 2024.

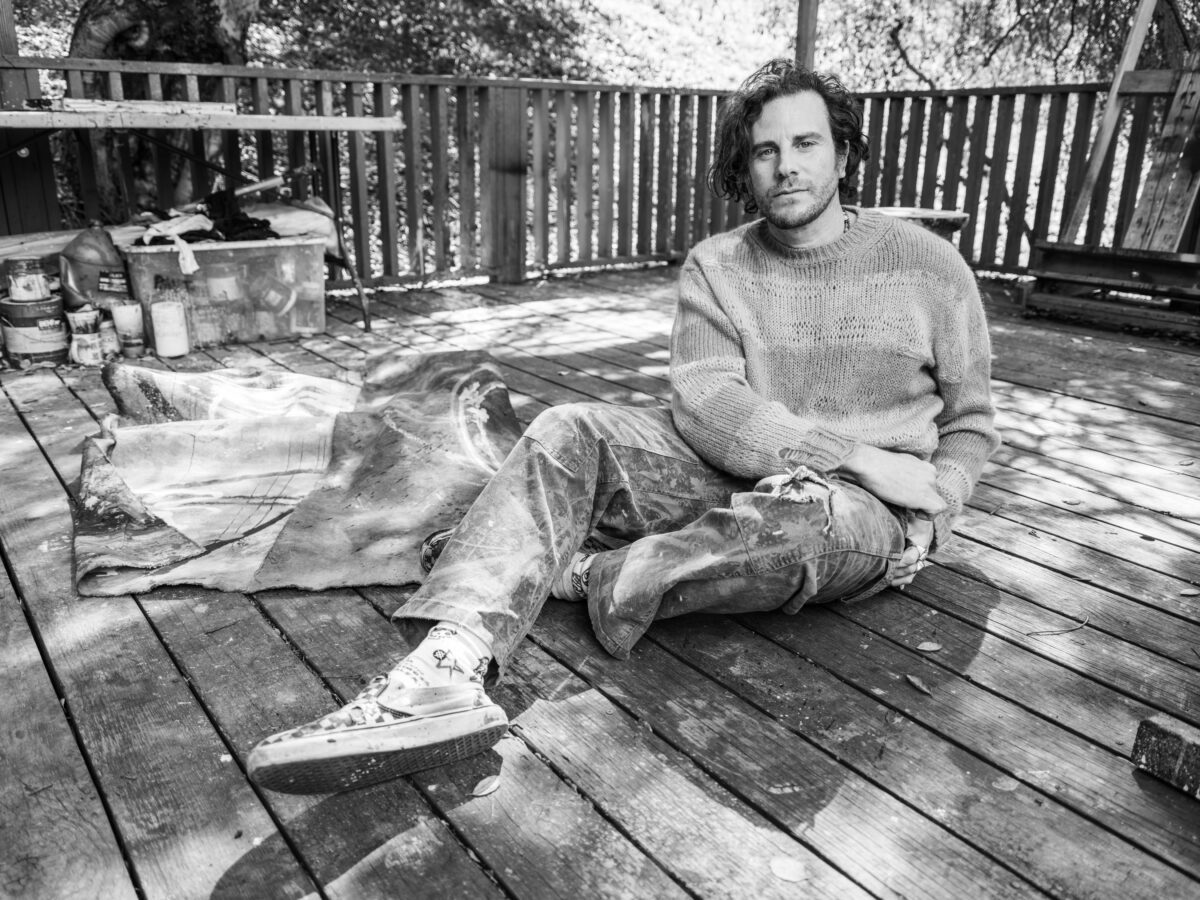

Cover Photograph:

Gregory Siff at his home studio in Sunland, California

Portrait by Rainer Hosch

All portraits by Rainer Hosch © 2024 for Installation Magazine

Polaroids by A. Moret