This year has been a ‘Storm of Hope,” in many ways. The phrase is anthemic and poignant in that it speaks to the eye of the storm that we have found ourselves in- one unprecedented rain after another. Robert Longo looks to the unflinching photographic documentation of these moments and renders them by hand so that they become the most iconic and captivating versions. The artist captures moments that are ingrained in our collective anxiety and reflective of our slow and gnawing tendency to engage in “doom scrolling.” A global pandemic, the threat to democracy, the fight for racial equality and civil rights, a desire to find permanence among displacement, an effort to rebuild after merciless natural disasters, right the wrongs of climate change, and reclaim our place as a community and as a people. Robert Longo’s large-scale drawings ask that we pause for a moment longer than we would normally look at photographs to consider the weight of the subjects, find the evidence of his hand rendering shades of charcoal and look ahead to the hope that comes to light after the final cloud has passed.

The phone rings and connects with Robert Longo in his New York City studio. It is the first time in recent memory that a call to the East Coast truly feels like a long-distance transmission.

The works presented in “Storm of Hope” reflects many of the principles that guide your artistic practice as they relate to the theme, scale, and medium. Despite the expansive scale of Jeffrey Deitch’s gallery space in Los Angeles, the images tower over the viewer and effortlessly fill the vast interior. What is the first impression that you hope to give the viewer when confronting your work? The hand referenced in “White Glove for Leon” is actually a clue.

They do use that trick that you think that they’re photographs. It always reminds me of how little people actually look and when they realize that they’re actually not photographs they look much more. I think the fact that people really want to see labor, they want to see expressions and things like that. Big dripping brushstrokes people get all excited about, you know? The fact is that messiness is in my work if you get really close to it. That’s a part of it.

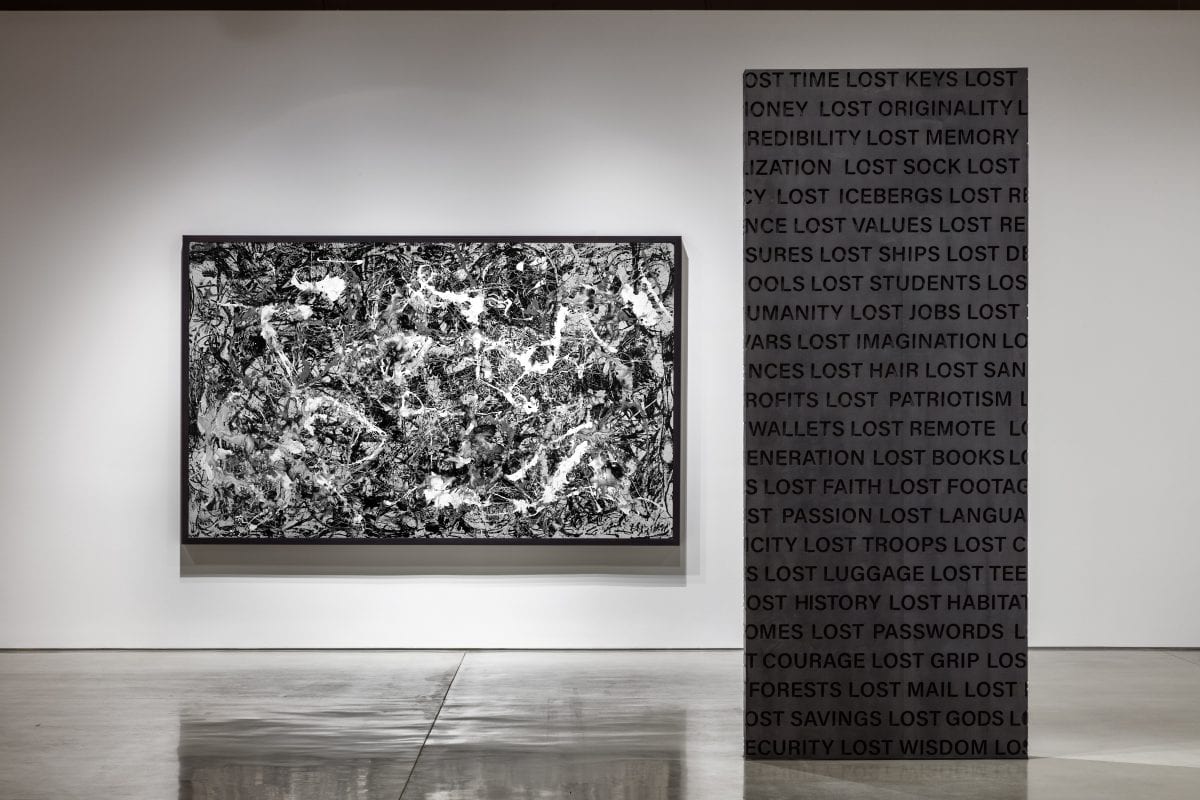

Photo by Joshua White. Courtesy of the artist and Jeffrey Deitch

Untitled (Nathan Bedford Forrest Statue Removal; Memphis, 2017), Untitled (Blank Pather), More Monolith, Untitled (Refugees Moonbird Sighting, Mediterranean Sea; May 5, 2017), and Untitled (White Glove for Leon) (Left to Right)

How do you sift through the barrage of images in the media “storm” to determine the inspiration for a drawing?

There are certain images that I just want to make and I use the internet to find them. I try to buy the rights as often as I can to buy the images and then what I’ve done, most of these images that I’ve used I’ve altered them. I alter it in a way where I amplify certain aspects of it. I combine other parts of it for instance the “

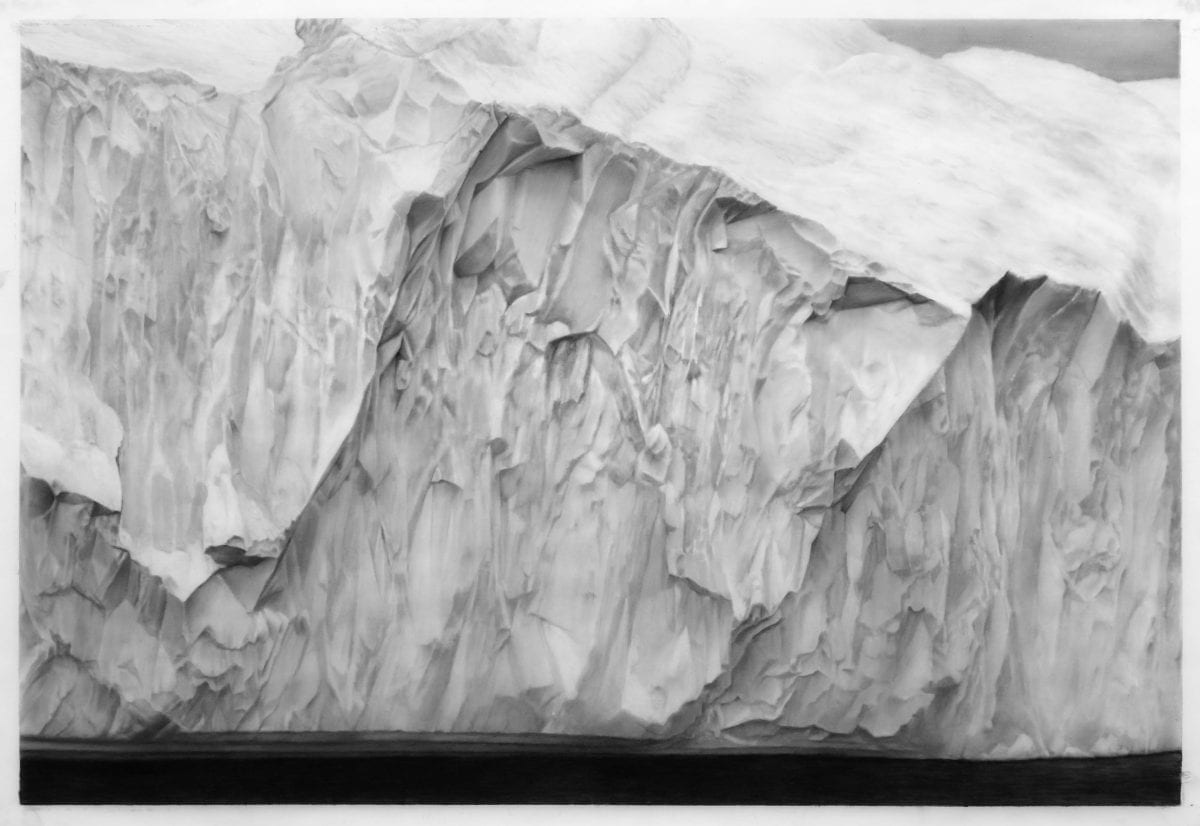

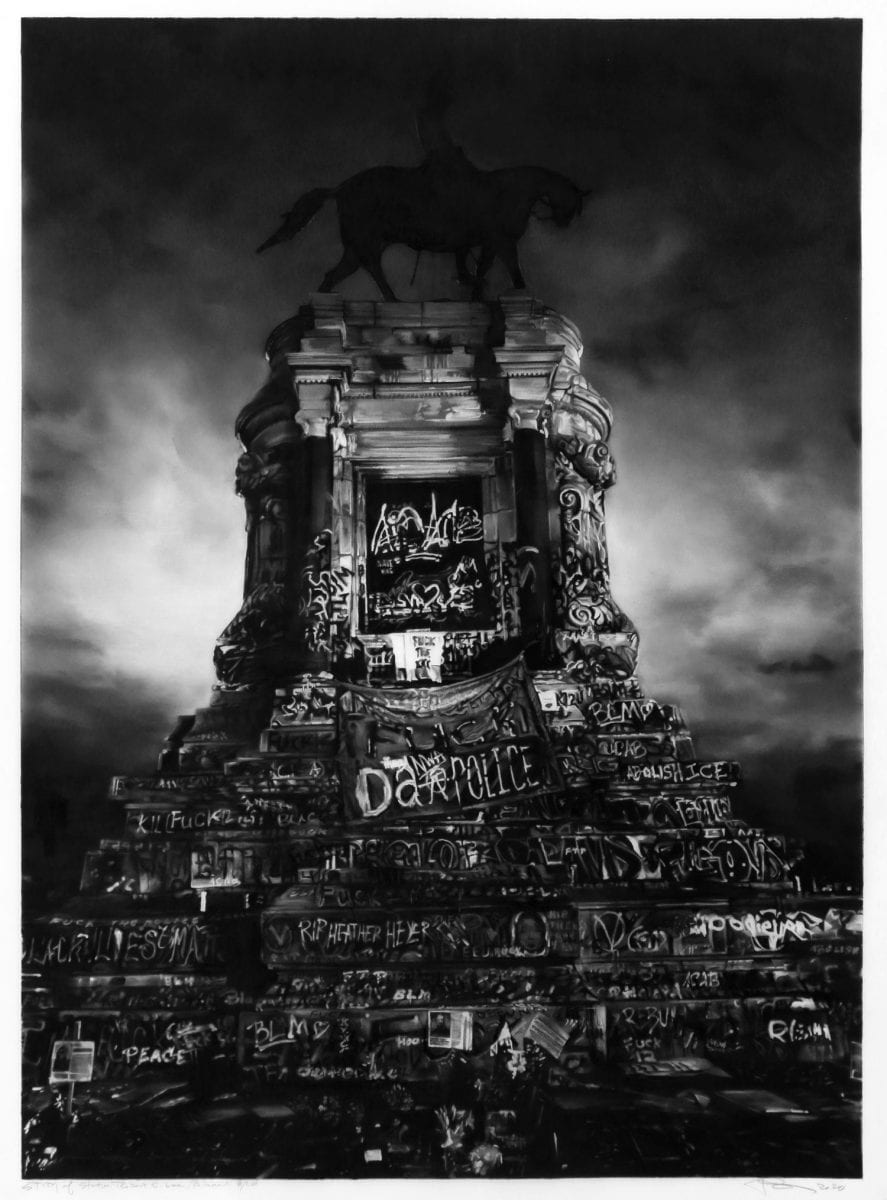

charcoal on mounted paper

107 3/34x 70 inches (image)

Courtesy of the artist; Metro Pictures, New York; Jeffrey Deitch, Los Angeles

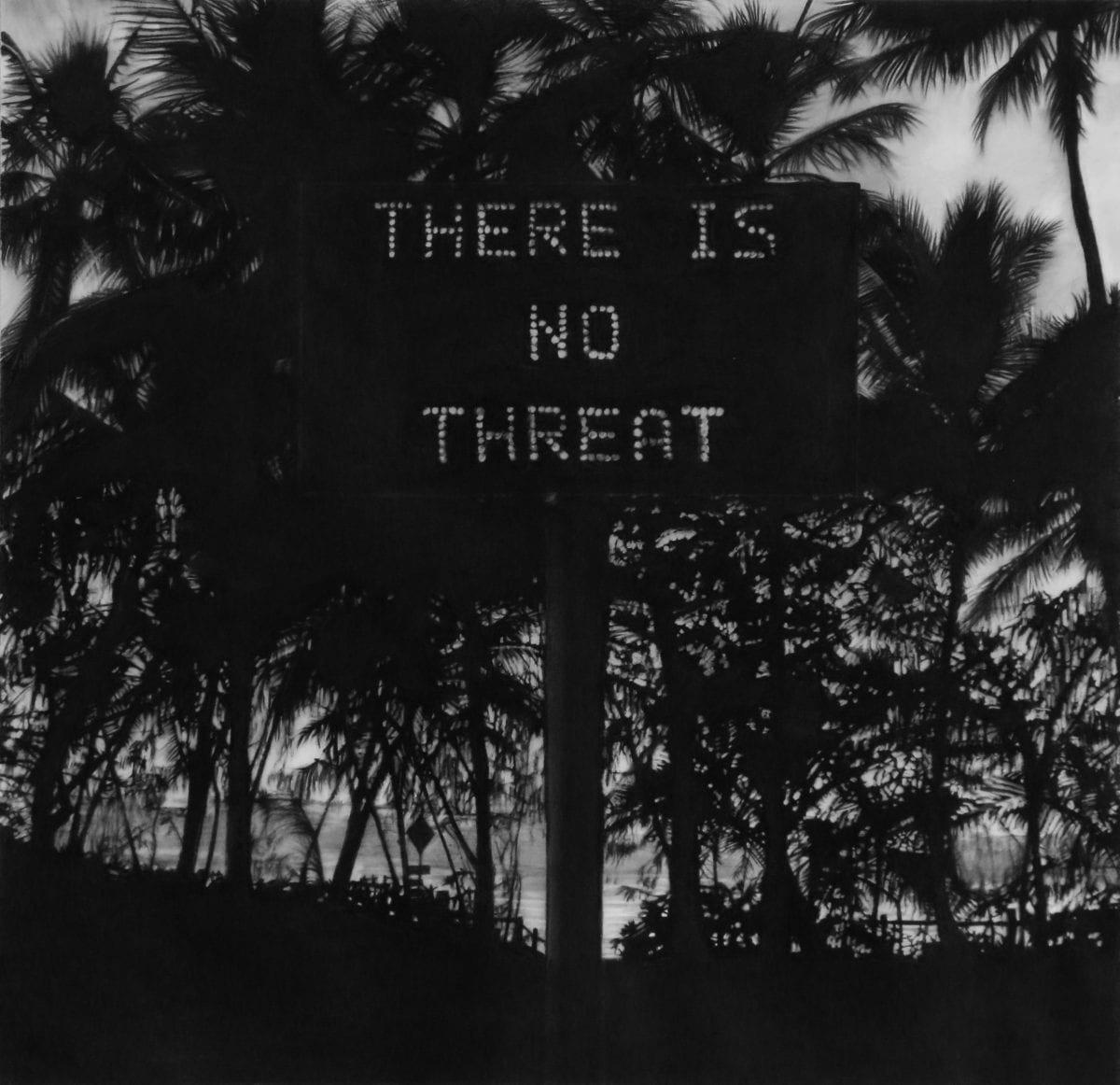

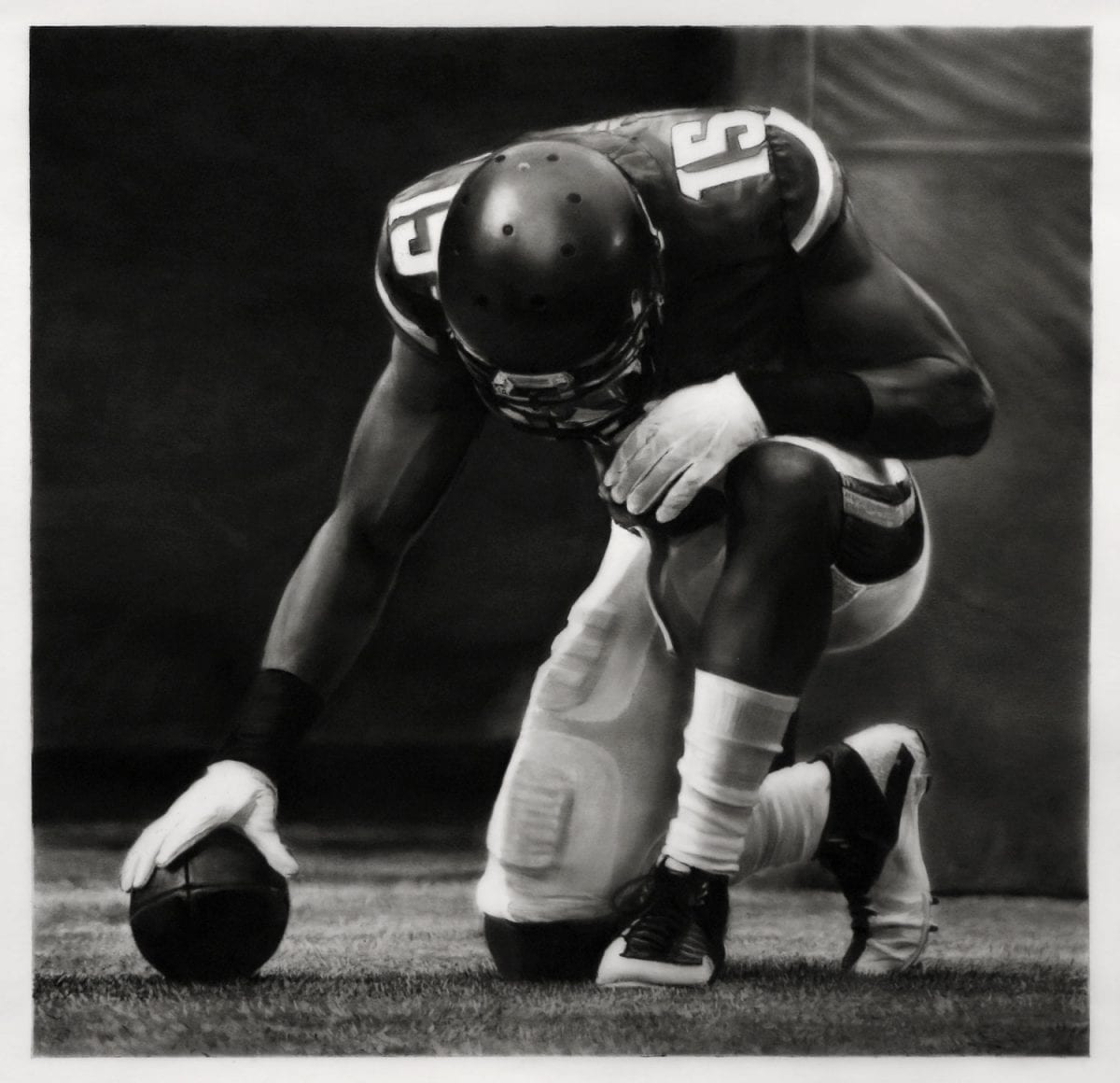

charcoal on mounted paper

88 1/4 x 70 inches (image)

Courtesy of the artist; Metro Pictures, New York; Jeffrey Deitch, Los Angeles

There is a sculptural quality to the work as it feels like the subject emerged by carving it out of the paper.

What’s ironic is that calling these things “charcoal drawings” is always somewhat humorous because if someone that I don’t know meets me and asks what I do and I say “charcoal drawings” they imagine these little tiny charcoal drawings. They have no idea that they’re these things that are on a scale of like paintings and I think that are these weird hybrids that categorically fit into traditions of painting not the tradition of drawing. I think the biggest difference between my stuff and painting is not so much that one is charcoal and one is painting it’s the way the process is- that traditional painting is you work from dark to light. Let’s say you’re painting a tree. You paint dark green first, light green. The last thing would be the white highlights. With my work, my work is the opposite. I work from white to dark. So the white in all the pictures is the white of the paper so I work from white to dark. The last thing that I usually do in these drawings is the black black which has these very heavy black marks. I have so many different values, I call them “colors of charcoal.” I have cool black, warm black, regular black, black black. They’re highly labor-intensive and they take a long time but one thing I also don’t have to deal with, I don’t have to deal with what painters have to deal with is drying time. I think painting is incredibly performance-based- it’s the original performance art. It’s so time-based. You have to make this plan with how to make the painting. When you look at a great painting you can see the way that things are seamed together and different areas of color. I mean the patience that’s required to make a painting is quite amazing. I’m a pretty impatient person so I think that drawing actually worked out quite well for me because I don’t have to wait for something to dry.

Photo by Joshua White. Courtesy of the artist and Jeffrey Deitch

Untitled (Jamal Ahmad Khashoggi; Istanbul, Turkey; October 2, 2018), Lost Monolith, Untitled (Nathan Bedford Forrest Statue Removal; Memphis, 2017,) Untitled (Blank Pather), Untitled (Refugees Moonbird Sighting, Mediterranean Sea; May 5, 2017,) Untitled (White Glove for Leon), and More Monolith, (Left to Right)

In creating “

Except the irony is that my drawing took so much longer than the painting took. It’s really weird when I did this whole group of works for “

Photo by Joshua White. Courtesy of the artist and Jeffrey Deitch

Untitled (After Pollock – Convergence, 1952), and More Monolith (Left to Right)

The salon wall located toward the back of the gallery presents a series of smaller images, studies that echo themes of displacement, unrest and put a face to the storms that we have experienced over the past year.

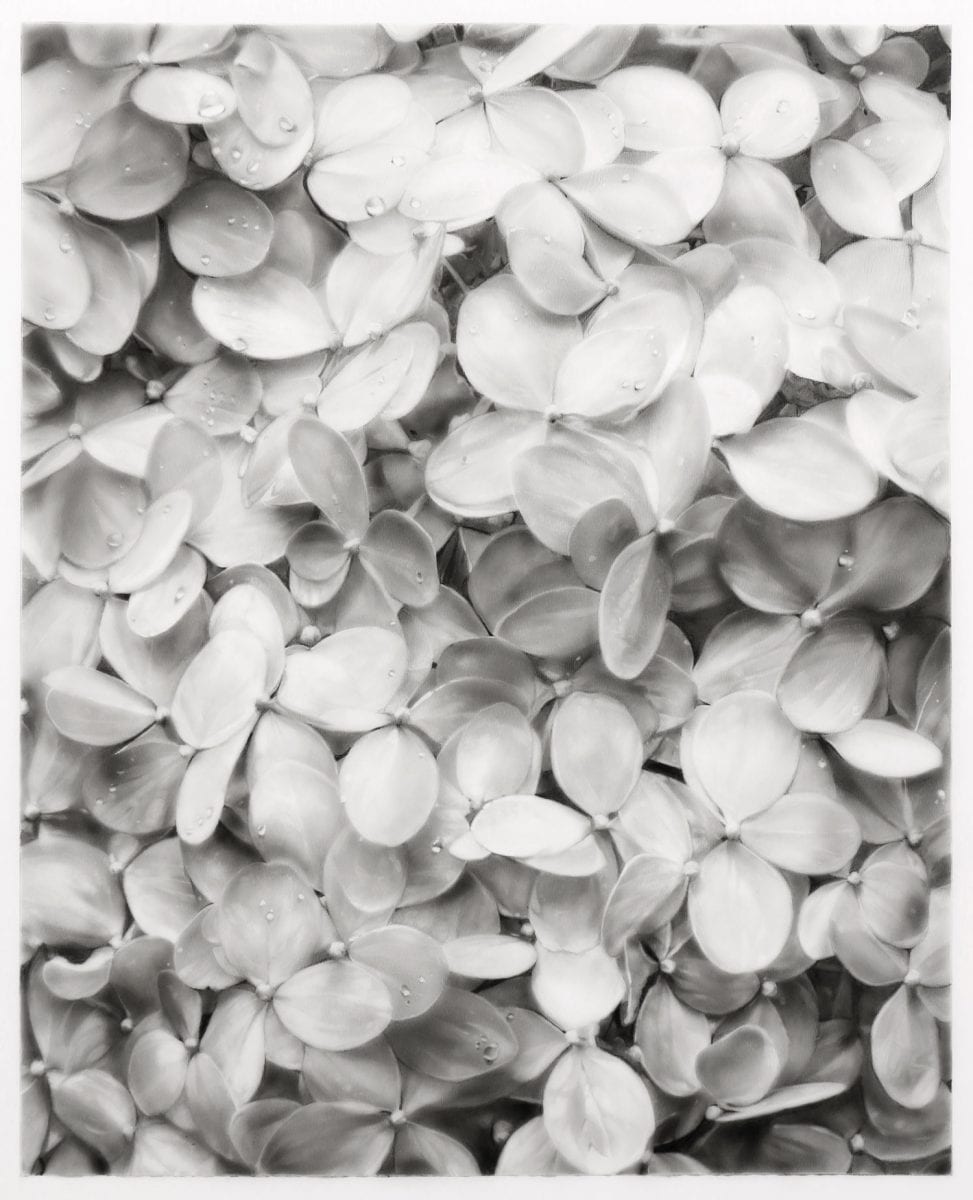

When things started to explode politically during the pandemic, I had been making a lot of these images for quite a while. The taking down of the Nathan Bedford Forest is quite an older drawing that I kept for a while. I thought that taking down Confederate monuments was one of the great moments in American history and I started doing those maybe in 2014 but what’s happened, with all these incredible images starting showing up with the protestors recently… now the world is actually really looking at things and people are actually paying more attention to things and visually they’re looking at a cop putting a knee on a black man’s neck and killing him and they’re watching it over and over again. That group of studies back there is kind of like the way my brain is, ya know? I realized what’s happened is that I can’t make these- the images now want to be more about nature and protest. I thought the image of the “

Photo by Joshua White. Courtesy of the artist and Jeffrey Deitch

ink and charcoal on vellum

21 x 31 1/2 inches (image)

Courtesy of the artist; Metro Pictures, New York; Jeffrey Deitch, Los Angeles

ink and charcoal on vellum

21 x 31 1/2 inches (image)

Courtesy of the artist; Metro Pictures, New York; Jeffrey Deitch, Los Angeles

ink and charcoal on vellum

15 1/2 x 16 inches (image)

Courtesy of the artist; Metro Pictures, New York; Jeffrey Deitch, Los Angeles

ink and charcoal on vellum

21 x 31 3/8 inches (image)

Courtesy of the artist; Metro Pictures, New York; Jeffrey Deitch, Los Angeles

ink and charcoal on vellum

15 3/4 x 32 15/16 inches (image)

Courtesy of the artist; Metro Pictures, New York; Jeffrey Deitch, Los Angeles

ink and charcoal on vellum

21 x 31 1/4 inches (image)

Courtesy of the artist; Metro Pictures, New York; Jeffrey Deitch, Los Angeles

ink and charcoal on vellum

29 3/4 x 21 1/2 inches (image )

Courtesy of the artist; Metro Pictures, New York; Jeffrey Deitch, Los Angeles

ink and charcoal on vellum

21 x 31 3/8 inches (image)

Courtesy of the artist; Metro Pictures, New York; Jeffrey Deitch, Los Angeles

ink and charcoal on vellum,

20 7/8 x 21 7/16 inches (image)

Courtesy of the artist; Metro Pictures, New York; Jeffrey Deitch, Los Angeles

ink and charcoal on vellum

26 7/6 x 20 15/16 inches (image)

Courtesy of the artist; Metro Pictures, New York; Jeffrey Deitch, Los Angeles

ink and charcoal on canvas

16 7/16 x 32 7/8 inches (image)

Courtesy of the artist; Metro Pictures, New York; Jeffrey Deitch, Los Angeles

ink and charcoal on vellum

20 15/16 x 26 inches (image)

Courtesy of the artist; Metro Pictures, New York; Jeffrey Deitch, Los Angeles

Photo by Joshua White. Courtesy of the artist and Jeffrey Deitch

Untitled (Iceberg for Greta Thunberg), Untitled (The Supreme Court of the United States (Split)), Untitled (After Pollock – Convergence, 1952), and More Monolith (Left to Right)

Photo by Joshua White. Courtesy of the artist and Jeffrey Deitch

Untitled (California Wildfire), and Untitled (Iceberg for Greta Thunberg) (Left to Right)

Photo by Joshua White. Courtesy of the artist and Jeffrey Deitch

Untitled (The Supreme Court of the United States (Split)), and Untitled (After Pollock – Convergence, 1952) (Left to Right)

You have described your large-scale charcoal drawings as “intimate immensities,” and I love that idea that something that a drawing can feel large when experienced in the gallery but is in fact scaled-down when comparing it to the actual source. Our relationship with

I think that the whole idea comes from that idea of trying to find this balance from something that’s highly personal and also socially relevant. Those three [“T

“

The idea that I’m trying to slow down images… the constant image storm that we live in. I was trying to pick images out of that to slow things down, so you look a little bit more. I did this drawing of a Jewish cemetery that someone had defaced with Swastikas, it’s a very large drawing. I have a subscription to the

charcoal on mounted paper

121 1/8 x 71 3/16 inches (left panel framed)

121 1/8 x 71 3/16 inches (right panel framed)

121 1/8 x 146 3/8 inches (overall framed)

Courtesy of the artist; Metro Pictures, New York; Jeffrey Deitch, Los Angeles

Photo by Joshua White. Courtesy of the artist and Jeffrey Deitch

Untitled (Capitol)

Photo by Joshua White. Courtesy of the artist and Jeffrey Deitch

Untitled (White House)

Photo by Joshua White. Courtesy of the artist and Jeffrey Deitch

Untitled (White House), and Untitled (Capitol) ( Left to Right)

Photo by Joshua White. Courtesy of the artist and Jeffrey Deitch

Untitled (Black Panther), Untitled (Refugees Moonbird Sighting, Mediterranean Sea; May 5, 2017,) Untitled (White Glove for Leon), and Untitled (White House) (Left to Right)

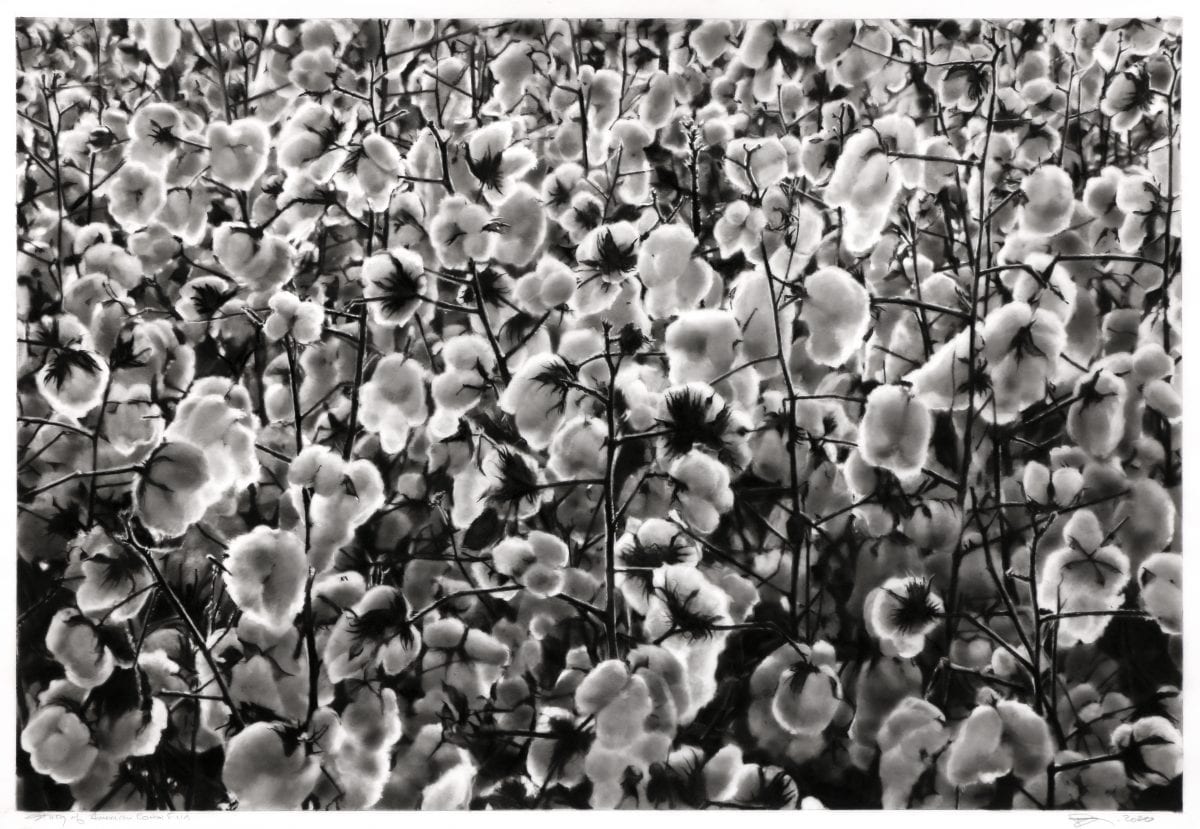

charcoal on mounted paper (7 panels)

121 1/8 493 3/8 inches (overall framed)

Courtesy of the artist; Metro Pictures, New York; Jeffrey Deitch, Los Angeles

charcoal on mounted paper

96 x 280 inches (overall image)

Courtesy of the artist; Metro Pictures, New York; Jeffrey Deitch, Los Angeles

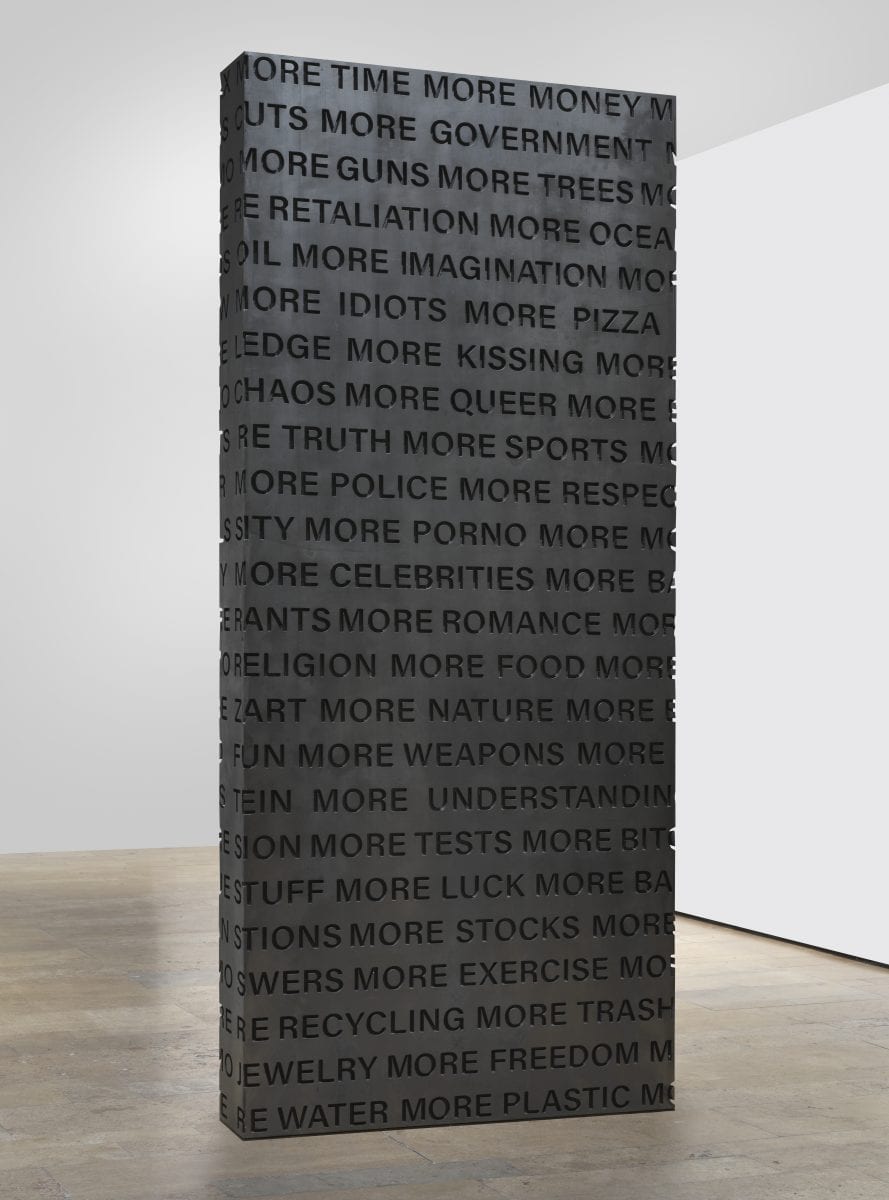

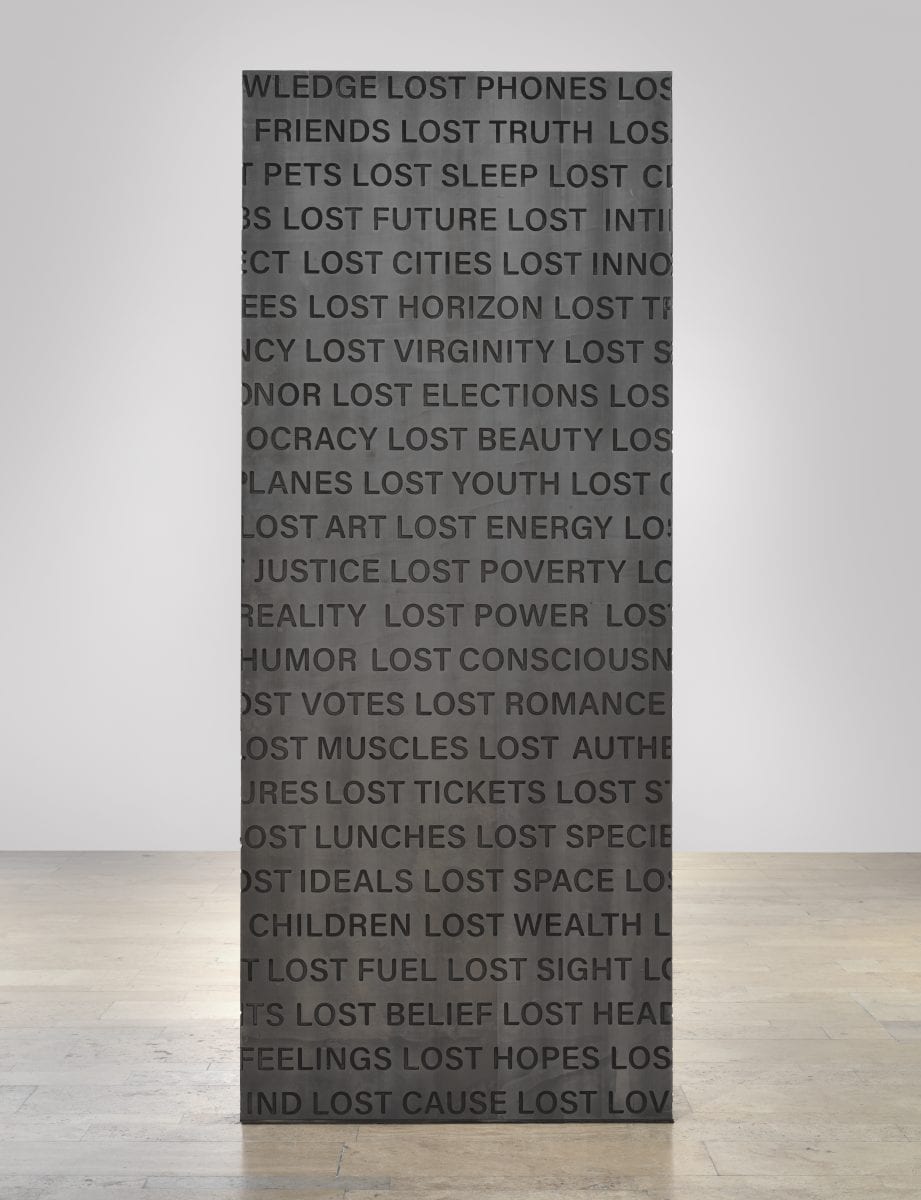

Along the lines of “slowing things down,” the two monoliths placed at either end of the gallery inspired me not only to get close to them but actively walk around them in either direction to create sentences from the text at varying heights. In confronting the monoliths I was immediately transported to the first and final scene of Stanley Kubrick’s “

That’s really great with you saying- that makes me very happy that you saw what was happening in those monoliths, it’s great. It is more about your movement in the round and they are connected to the drawing. The thing that’s really weird is the idea of trying to figure out how to make sculptures because I was trained, actually, my degree was in sculpture and the drawings in a weird way are very sculptural because they’re like carving out the image… it’s like erasing is a really big part of it. I’m constantly tortured trying to find the physical manifestation of my work and it’s always been really difficult. And it comes out in things that don’t necessarily look like my work but I always thought it’s not important that it looks like your work but feels like your work.

Urethane resin, Epoxy resin, steel

132 x 54 x 8 inches

Edition 1 of 3, 1AP

Courtesy of the artist; Metro Pictures, New York; Jeffrey Deitch, Los Angeles

Urethane resin, Epoxy resin, steel

132 x 54 x 8 inches

Edition 1 of 3, 1AP

Courtesy of the artist; Metro Pictures, New York; Jeffrey Deitch, Los Angeles

Perfect! I can’t wait to wake up in the morning to go to work. I’m excited about what I’m doing and things like that but that morning I could not find my fucking keys and I couldn’t find my phone and then someone, a friend of mine had just died and then I realized I was really hungry and I wanted more of the food and I realized I shouldn’t be eating it and then the whole thing- I wanted one work to be bigger but I couldn’t make it bigger. I wanted the work to be more and I started realizing that this “loss” and this “more” stuff are these boundaries of life you know? I want more of this and I lost that and it became these kinds of goalposts of my life in a weird way.

About an hour after the interview, there was an incoming call from an unknown number on the second ring. “Longo here,” the artist began. No preamble. Just straight to the point. After reviewing preliminary notes he had discovered that the original title for “Storm of Hope” had been “Sea of Troubles,” a Shakespearian allusion to Prince Hamlet’s soliloquy.

To be, or not to be? That is the question—

Whether ’tis nobler in the mind to suffer

The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune,

Or to take arms against a sea of troubles,

And, by opposing, end them? To die, to sleep—

No more—and by a sleep to say we end

The heartache and the thousand natural shocks

That flesh is heir to—’tis a consummation

Devoutly to be wished! To die, to sleep.

To sleep, perchance to dream—ay, there’s the rub,

For in that sleep of death what dreams may come

When we have shuffled off this mortal coil,

Must give us pause. There’s the respect

That makes calamity of so long life.

Featured Image:

Robert Longo, Untitled (The Supreme Court of the United States (Split)), 2018

charcoal on mounted paper

121 1/8 x 71 3/16 inches (left panel framed)

121 1/8 x 71 3/16 inches (right panel framed)

121 1/8 x 146 3/8 inches (overall framed)

Courtesy of the artist; Metro Pictures, New York; Jeffrey Deitch, Los Angeles